Service Locator

- Angler Endorsement

- Boat Towing Coverage

- Mechanical Breakdown

- Insurance Requirements in Mexico

- Agreed Hull Value

- Actual Cash Value

- Liability Only

- Insurance Payment Options

- Claims Information

- Towing Service Agreement

- Membership Plans

- Boat Show Tickets

- BoatUS Boats For Sale

- Membership Payment Options

- Consumer Affairs

- Boat Documentation Requirements

- Installation Instructions

- Shipping & Handling Information

- Contact Boat Lettering

- End User Agreement

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Vessel Documentation

- BoatUS Foundation

- Government Affairs

- Powercruisers

- Buying & Selling Advice

- Maintenance

- Tow Vehicles

- Make & Create

- Makeovers & Refitting

- Accessories

- Electronics

- Skills, Tips, Tools

- Spring Preparation

- Winterization

- Boaters’ Rights

- Environment & Clean Water

- Boat Safety

- Navigational Hazards

- Personal Safety

- Batteries & Onboard Power

- Motors, Engines, Propulsion

- Best Day on the Water

- Books & Movies

- Communication & Etiquette

- Contests & Sweepstakes

- Colleges & Tech Schools

- Food, Drink, Entertainment

- New To Boating

- Travel & Destinations

- Watersports

- Anchors & Anchoring

- Boat Handling

- ← Seamanship

Man Overboard Rescue For Powerboats

Advertisement

Few of us plan for a crew member to fall overboard. Getting that person back aboard is harder than you think.

Man Overboard Modules (MOMs) like the Switlik 600 provide flotation and visibility.

Unless you do the right things, fast, when someone falls overboard, that person could be lost. Man-overboard (MOB) fatalities make up 24 percent of all boating deaths. Our BoatUS Foundation for Boating Safety and Clean Water has studied these incidents over a five year period and created a picture of the typical accident. The majority of cases do not involve bad weather, rough seas, or other extenuating circumstances. "Most happen on relatively calm waters, on a small boat that's not going very fast," said Chris Edmonston, president of the BoatUS Foundation. "Victims tend to be men. Fishing is a prime activity, and in many cases, alcohol is involved."

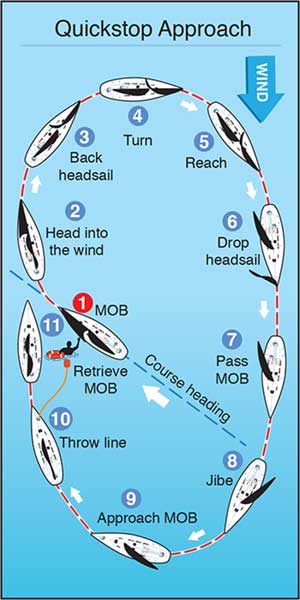

Numerous articles have been written about recovering a lost crew member from a sailboat, but MOB procedures for powerboaters have seldom been addressed. In light of the profile above, we present a general overview of MOB scenarios and procedures for the benefit of all boaters, no matter the size of your boat. We include an accompanying sidebar, "Brother, Save Thyself," about how to get back aboard a small boat. We also present and illustrate the Quick-Stop method, favored by many sailboaters:

Know Your Boat's Characteristics

When someone falls overboard, it's critical to get to the victim quickly. Think about how you'll do this on your boat without endangering the victim with your prop. Consider the freeboard of your boat. If it's high, this makes it difficult to get a victim back aboard. If your boat has a squared chine (bottom), waves may cause the boat to crash down on a victim who's alongside, while a rounded chine may push the victim away from the boat and out of reach. Look at your stern platform. Will it help, or plunge down on a victim, pushing him underwater and perhaps into the props? Before there's an emergency, consider how these factors affect your boat's maneuverability, and fit your boat out with gear that might mitigate some of these challenges (see MOB equipment sidebar below).

Equipment To Locate MOB

No matter what size or type of boat you have, you should carry:

- USCG-approved floating cushions, ring buoys, and life jackets with colors that stand out at sea and that are readily available.These can help the victim float and help lead you back to him. (Life jackets with mirrors and waterproof lights are a smart idea.)

- A GPS with MOB feature.

Here are other MOB-location gear to consider carrying:

- AutoTether Screamer Wireless Alarm System sounds an alarm that a crewmember wearing a transmitter has gone overboard. The sooner you know you have an MOB, the more likely you are to find the victim in time.

- SafeLink R10 SRS (Survivor Recovery System) utilizes both GPS technology and the AIS system to help you and nearby AIS-equipped vessels find a victim.

- ResQLink+ by ACR is a personal locator beacon (PLB) worn by the victim that enables USCG to find and retrieve him. (Note: PLBs alert authorities, but not you, to the MOB. An MOB alarm enables you to respond immediately — particularly important if the water is cold and the victim has no flotation.)

- An MOB floating rescue flagpole that you can toss over the side. It unfurls a bright yellow flag that's easier to spot from a distance.

Equipment To Retrieve MOB

According to rescue professionals, getting an exhausted victim back aboard who may be unable to assist in the rescue can be far more challenging than returning to the victim. Every boat should be equipped with an easy way for someone to get aboard from the water.

On most boats, the best solution is a boarding ladder that's structurally strong, well-designed, easily put in place, and long enough for your freeboard and for the victim to climb easily. The ladder should be relatively vertical, stand off the hull for toe clearance (which a rope ladder doesn't do), have nonskid steps, and be capable of firmly attaching to the boat. Generally, a ladder mounted to the side is safer and easier to use than one on the stern.

If your boat has low freeboard and came with a boarding ladder, beware: Many built-on swing-down ladders don’t swing down deeply enough for an exhausted person to climb up, and they don't have adequate hand grips fastened to the boat for the victim to grab and pull. Most people have the greatest strength in their legs, not their arms. Improve your ladder and hand grip, or get a long ladder that hooks over the gunwale, such as the West Marine Portable Gunwale-Mount Boarding Ladder.

Lines with loops at each end can also be useful. They need to be of proper length to rig quickly for use as a handhold, support, or recovery sling.

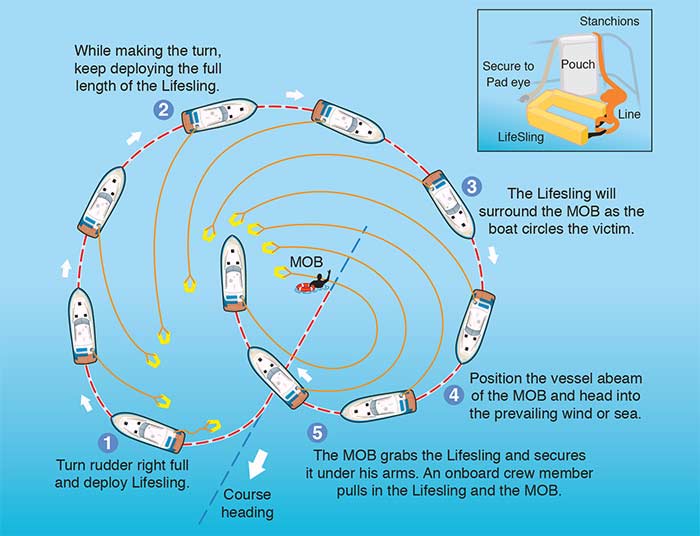

Beyond these essentials, you may want to carry a MOM (Man Overboard Module) and/or a Lifesling. MOMs come in several models ranging from floats to platform rafts that rapidly release and inflate. The Lifesling has a floating yellow yoke, and you can buy a 5:1 purchase tackle to help pull the victim up .

Your boat must be set up in advance to properly utilize this gear. For example, the tackle that you can purchase with a Lifesling can help a weak person lift a heavy person out of the water. But a secure attachment point on the boat high enough above water (generally about 10 feet above the waterline) must be installed in advance. If there isn’t a high enough place to attach a securing point, the Markus Scramble-net or other equipment that doesn't require as high an attachment point may work for you.

Consider Your First Steps Before The Worst Happens

If you have an MOB, the following basic procedure needs to happen immediately. To prevent confusion from impeding swift action, practice. But remember, your exact actions must depend on many variables.

1. The instant someone falls overboard, yell "Man overboard!" to alert crew to the emergency, and establish an unceasing visual on the victim. If you have enough crew, assign this job to one person and let nothing interfere with that person keeping the victim in sight and pointing at the victim from that first moment on.

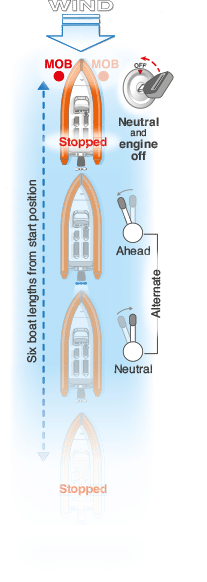

2. If you're unsure of where the person is or if there is a chance the props could endanger him, stop the boat and ensure that the props don't injure the victim now or later.

3. Activate your GPS MOB button if you have one.

4. Throw MOB gear, life jackets, flotation cushions anything that will help the victim float and help you keep track of him, but not so much as to confuse a search.

5. Return to and attempt to retrieve the victim. Several alternative methods are illustrated on these pages and discussed in the next section.

6. If the situation is life-threatening, call mayday three times on VHF 16. Then say, "Man overboard," and give your location, boat description, and the description of the victim. Do this three times in succession. Don't hesitate to issue a mayday you can always cancel it if you get the person back aboard safely.

Sea and wind state: When you get closer to the victim, determine how much and how fast the wind and sea are pushing your boat, which is having the most effect, and how fast you're drifting. If the sea is rough, it may be dangerous to come alongside the victim, especially if he's exhausted or injured. Go slowly. If he does not have flotation, try to toss him a flotation and/or retrieval device as you approach.

Water temperature: Sudden cold-water immersion can cause involuntary gasp reflex or cardiac arrest. Often a surprised MOB victim will instinctively gasp and suck in a large volume of water, which could lead to drowning. Also, a victim's loss of body heat may weaken and disorient him, limiting his ability to swim or help in his rescue. The victim should try to maintain core body heat for as long as possible by keeping his arms down and crossed, and knees bent up to his chest, if possible. Wearing a life jacket helps the victim's odds significantly.

Physical condition of victim: Excess weight, poor swimming ability, panic, lack of arm strength, injury, hypothermia, and other factors make retrieval extremely challenging. The person in the boat may need special equipment or assistance to get the victim aboard.

Skill, size, and ability of person(s) aboard: One person aboard a high-freeboard boat may find it almost impossible to get a victim aboard, particularly if either person isn't in good physical condition, or if the larger and/or more skilled person is in the water. Think about an alternative, such as a Lifesling, or another system that could work on your particular boat.Visibility:

Take a look around. If visibility is poor, slow down and make sure you know where the victim is. If an approaching fog bank or squall could reduce visibility soon, get back to the victim before you lose sight of him.

Other boats: If you're in a rough inlet with many boats racing past, position your boat to protect the victim and begin visual warning signaling. In some cases, it may be prudent to wait for help before you begin retrieval. One example would be if you were alone on board and another boat nearby with strong experienced swimmers and retrieval gear responded to your distress call and was on their way to the scene.

Sobering MOB Facts

Our BoatUS Foundation has created a snapshot of boating fatalities that occurred between 2003 and 2007, a five-year span that gives good insight on MOB accidents and how they happen, so that we can work to help lower those numbers. In that timeframe, 749 of the 3,133 total U.S. boating fatalities were MOB:

- 24% were characterized as "falls overboard."

- 24% died at night, and 76% died during the day.

- 82% were on a boat under 22 feet in length.

- 63% didn't know how to swim.

- Only 8% of the non-swimmers were wearing a life jacket.

- 90% of accidents occurred when water conditions were calm or had less than 1-foot chop.

- Just 4% of the boats had two engines.

- 85% of fatalities were men.

- Average age was 47.

- During the day, alcohol played a part in 27% of the deaths.

- At night, alcohol played a part in 50% of the deaths.

- Falling overboard while fishing accounted for 41% of the deaths.

— Chris Edmonston

Practice, Practice, Practice

If you want to save an MOB victim, the time to start is now. Begin planning and practicing what you'd need to do in your circumstances in your boat. This helps generate intuitive, appropriate reactions.

Practice MOB techniques by throwing a fender with a bucket attached into the water. Return to it, approach it, and get it aboard while being extremely careful that you keep the props away from the "victim."

The best equipment may be useless unless you know how to deploy it without thinking. For example, if you have a Lifesling with tackle, on a calm day, near shore, practice putting a person in the water, rig it, and use it. Also, practice with the "victim" pretending helplessness. The "victim" should be wearing a life jacket.

Practicing may teach you that the best you can do is to stabilize the victim safely alongside and call the Coast Guard for help on the VHF. Unless you're in really cold water, it usually takes a relatively long time to become unconscious due to hypothermia. The key is to keep the victim from drowning, getting injured, or becoming disconnected from the mother ship.

As you practice, think through contingency plans for each of the three steps necessary to retrieve a person who has gone over the side: Return to the victim, approach the victim, and get the victim aboard.

Return to the victim: If a person goes over the side while the boat is underway, it's normally best to turn toward the side he went over, in order to swing the stern and props away from the victim.

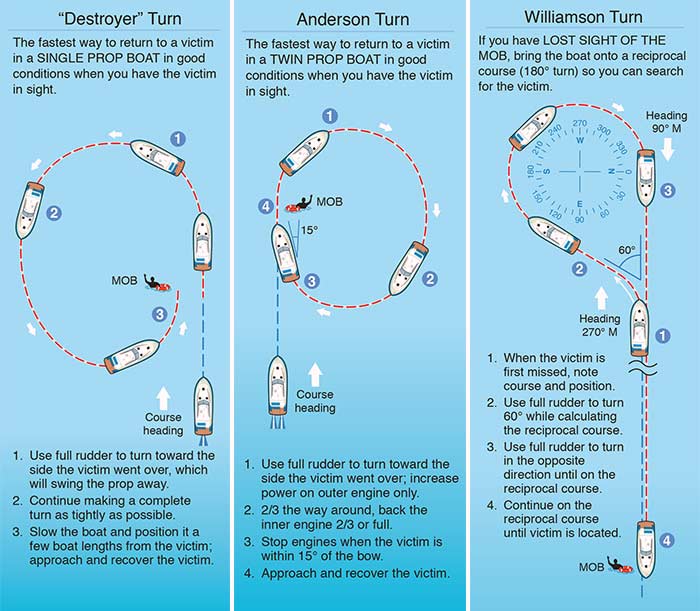

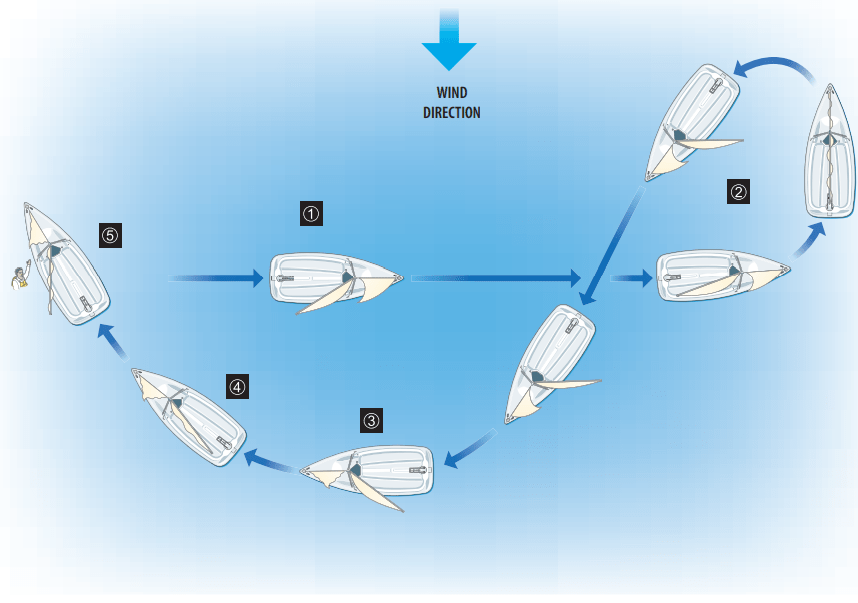

Three Alternatives For Returning To A Victim

You should know instantly when someone goes over if you're in a smaller center console. But in a larger boat, more time may pass before you notice. To find the victim, you will need to calculate and steer a reciprocal course back to the location. The illustrations above show several methods for returning to a victim. For more information, refer to the Coast Guard Boat Crew Seamanship Manual.

If you need to rely on the MOB feature on your GPS to find the victim, learn where that button is, now, so you can push it while doing everything else needed at the same time. Be sure you will understand, even under duress, what the GPS is telling you.

Approach the victim: Two effective alternatives for approaching the victim are illustrated above. Decide on the best approach based on factors including but not limited to sea state, current, whether other boats are approaching, your boat's characteristics, and your crew's capabilities. Have those responsible for pulling the victim aboard (hopefully more than just you) in position and ready.

In most situations, it is safest to approach the victim with your bow facing into the wind and waves. If possible, throw him a line when you get close enough. Then turn off the engine(s), pull the victim in to the boat, and bring him to the ladder-hoisting area. This will minimize the chance of striking the victim with the propeller.

On a smaller boat without a lot of windage, it may be safer to come to a controlled stop upwind of the MOB and drift down on him, with crew ready to reach over and grab him. This may prove challenging on a boat with a lot of windage and high freeboard, but relatively easy on a center console. In some circumstances, it may be better to approach downwind but circle closely and come into the wind next to the victim.

While it is usually safest to approach the MOB with the wind and waves over the bow, this may not be possible in a narrow channel, in large waves, near obstructions, or in other circumstances where maneuverability is limited. To prepare for these situations, practice approaching the victim with the wind and sea behind you, very slowly. Maintain control of the boat to avoid floating over the victim.

Lifesling, Towline, Or Ski-Rope Retrieval

If you have a Lifesling or other retrieving line, slowly circle the victim, towing the line behind the boat until it comes within the victim's reach (see illustration above). Then stop the boat and pull the victim in.

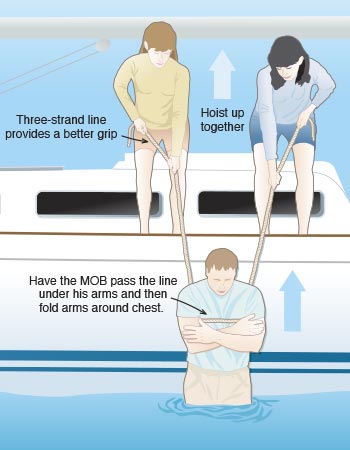

Get the victim aboard: The very best way to get a victim back aboard is with a strong, well-built ladder. If you don't have a ladder or a Lifesling with tackle, a recovery line looped under the victim's arms (see illustration) may enable one or more people to pull him up over a relatively high freeboard.

When trying to retrieve a victim and bring him back aboard into a center console with low freeboard, it may help to position the victim facing the boat with both arms reaching upward. If the person aboard has the necessary strength, he should reach down and grasp the victim's wrists; the victim should grab the rescuer's wrists; and the rescuer should lift the victim straight out of the water. If you have a net or tarp, you may be able to secure one side to your gunwale, carefully work the net/tarp under the victim, then hold him in place until more help comes.

MOB testing has proven that if the victim is helpless and unable to assist, it will be very difficult to get him back into the boat. If you have a strong swimmer aboard, conditions are appropriate, and it's safe to do so, consider having that person (wearing a life jacket) go in and help the victim get to and climb up a strong ladder. But remember that you now have two people in the water, and, potentially, two victims at risk. Calling mayday, keeping the victim next to the boat, and waiting for assistance may be a more prudent course of action.

Brother, Save Thyself

Approximately half of the 749 MOB fatalities reported in our "MOB Facts" sidebar occurred on boats with only one person aboard; in 190 fatalities (about 25 percent), only two people were aboard. This means that, many times, victims fall overboard from smaller boats – many while fishing alone or with one friend; they can't get back aboard their boats, and drown.

So, for small-boat operators, think about how to set up your boat so that you can effectively get back aboard yourself:

- Use an engine cut-off switch, especially if you're operating the boat alone.

- Make sure there's a sturdy boarding ladder either permanently attached to the boat, or where it can be reached from over the side.

- It can pay to simply secure a line to the boat, tie a loop in the end (large enough for your foot), and hang it over the side so you can reach it from the water. With the engine off, practice climbing aboard using the loop.

- On some boats, it may be possible to get back aboard using the back of your motor as a step. (Turn off the motor and remove the key before experimenting.)

- Wear a life jacket.

— C.E.

Crew Briefing

Each time you go out, make an MOB briefing part of your departure routine. Show people where life jackets are stowed. Better yet, encourage your crew to wear them. Most drownings occur quickly. If your crew are wearing life jackets when they go in the water, they'll stay alive longer and you will have a much better chance to save them.

Stress the necessity that someone keep an eye on an MOB victim at all times, point out throwing devices and recovery gear, show how they work, and explain challenges such as plunging stern platforms and rolling hard chines. Show crew where the radio is and how to broadcast a mayday. Also, before you set out with your crew for the day, identify a second-in-command (the person with the most skill other than you) who can take control in case you're the victim. The enemy of a successful rescue is confusion. There should be less of it if the skipper has set the stage.

Related Articles

The truth about ceramic coatings for boats.

Our editor investigates the marketing claims of consumer-grade ceramic coatings.

Fine-Tune Your Side Scan Fishfinder

Take your side-scanning fishfinder off auto mode, and you’ll be spotting your prey from afar in no time

DIY Boat Foam Decking

Closed-cell foam flooring helps make boating more comfortable. Here’s how to install it on your vessel

Click to explore related articles

Technical Editor, BoatUS Magazine

One of the top technical experts in the marine industry, Tom Neale, BoatUS Magazine Technical Editor, has won nine first-place awards from Boating Writers International, and is author of the magazine’s popular "Ask The Experts" column. His depth of technical knowledge comes from living aboard various boats with his family for more than 30 years, cruising far and wide, and essentially learning how to install, fix, and rebuild every system onboard himself. A lawyer by training, for most of his career Tom has been an editor and columnist at national magazines such as Cruising World, PassageMaker, and Soundings. He wrote the acclaimed memoir All In The Same Boat (McGraw Hill), as well as Chesapeake Bay Cruising Guide, Vol. 1. These days, Tom and his wife Mel enjoy cruising their 2006 Camano 41 Chez Nous with their grandchildren.

BoatUS Magazine Is A Benefit Of BoatUS Membership

Membership Benefits Include:

Subscription to the print version of BoatUS Magazine

4% back on purchases from West Marine stores or online at WestMarine.com

Discounts on fuel, transient slips, repairs and more at over 1,200 businesses

Deals on cruises, charters, car rentals, hotel stays and more…

All for only $25/year!

We use cookies to enhance your visit to our website and to improve your experience. By continuing to use our website, you’re agreeing to our cookie policy.

- Find A School

- Certifications

- North U Sail Trim

- Inside Sailing with Peter Isler

- Docking Made Easy

- Study Quizzes

- Bite-sized Lessons

- Fun Quizzes

- Sailing Challenge

Handling Emergencies: Man Overboard

By: Zeke Quezada, ASA Safety

Every man or woman overboard situation should be treated as a very serious matter, even in seemingly balmy conditions. In cold waters or cold weather, in restricted visibility or at nighttime, or in rough seas, the chances for a positive outcome diminish. Any delay in recovering the person in the water stacks the odds against his chances of survival. the best advice is to do all you can to prevent anyone from ever going overboard, but be prepared to handle the situation if it does occur.

Focus on Recovery

If somebody does go overboard, the entire crew must focus on one goal: getting him back in the boat. To do that, you have to do four things as fast as possible but without causing further risk to the boat and the rest of the crew.

- Keep the person overboard in sight.

- Throw him a life ring or some other type of buoyant device.

- Get the crew prepared for the recovery, return on a close reach, and stop the boat to windward of him and close enough to retrieve him.

- Bring him back on board.

Sailors have developed several techniques for returning to a man overboard (MOB) and in any situation, the exact one chosen will depend on the experience and skill of the crew, the number of crew on board, the type of boat, weather conditions, and perhaps other factors. In the end, all recovery techniques are more similar than different, as they all share the four key components mentioned above.

First response: “Y, T, P, S, C”

- Yell to alert the crew.

- Throw a Type IV or any other buoyant device toward the MOB.

- Point to keep the MOB in sight.

- Set the MOB button on the GPS.

- Call on VHF 16.

After that, everyone’s attention (apart from the spotter, whose job it is to keep the MOB in sight) turns to the goal of getting the boat to the MOB, attaching the MOB to the boat, and bringing the MOB back aboard.

Watching and pointing to the MOB is crucial because as soon as the boat turns to begin the recovery maneuver, the crew, busy at their stations, will lose their orientation with respect to objects outside the boat.

Method for recovery of MOB (Man Overboard)

The Figure-Eight Method

You begin this maneuver by sailing away from the MOB. This may feel wrong, but the crew needs time to prepare the boat and recovery equipment and distance to be able to approach at the right point of sail, slowly, in control, and equipped to retrieve the MOB. While one crew prepares the line with the bowline, another can put in place some means of recovering the MOB, such as a boarding ladder.

- Bring the boat onto a beam reach and continue sailing away from the MOB. A distance of four to six boat lengths (20 to 30 seconds) should be sufficient — the distance will be shorter in lighter winds and longer in higher winds. While the boat is on a beam reach, the helmsman, guided by the spotter, glances back at the MOB two or three times while preparing the crew for the next maneuver.

- Tack the boat and sail back on a broad reach aiming a few boat lengths downwind of the MOB. Ease the jibsheet to reduce power.

- Sail to a point from where you can head up onto a close reach aiming just slightly to windward of the MOB. Knowing exactly when to turn onto your final approach will take practice. You need enough distance on the closereaching approach to slow the boat significantly before reaching the MOB.

- Just as you did in your slowing drills near a buoy, sailing on a close reach, luff the mainsail to slow the boat to a crawl, but re-trim it to pick up speed if you are falling short of the MOB.

- Come alongside the MOB at a speed of less than one knot, a very slow walking pace. Keep in mind that your ability to maneuver is limited, and once the boat stops altogether, you lose complete steering control.

- As soon as you have gotten close to the MOB, your highest priority is to connect him to the boat with a line. Get the line with the bowline around his torso. DO NOT allow the boat to move away from the person in the water — the time expended making a second maneuver and approach could be costly.

- Once connected to the MOB, turn the boat farther upwind to slow the boat and avoid blowing over the MOB. At this stage, the boat will be hard to control. Expect a certain amount of chaos on board and stay focused on the priority of bringing the MOB into the boat.

Placing the boat just to windward of the MOB is considered the safest approach in most conditions. It will offer him some shelter from the wind and waves and make it easier to throw him a line. If you have overshot, luff the sails and the boat will blow downwind toward the MOB. Be especially careful, though, that you don’t allow the boat to be blown on top of the MOB.

Additional MOB recovery methods are covered in Sailing Made Easy : The Official Manual For The Basic Keelboat Sailing Course. These tips are directly from the text of the ASA 101 course.

Practice, Practice, Practice

Despite the variety of techniques for the middle stage as the boat turns back for the pick up, any MOB drill aboard a sailboat begins and ends with exactly the same steps. The methods share more similarities than differences. You will learn more options as you progress with your sailing instruction, and they are discussed in Coastal Cruising Made Easy . But reading instructions for dealing with an emergency will only get you so far. Practice, with the entire crew, is crucial. Remember, the sooner you get back to your MOB, at a very slow speed and with the crew prepared for the retrieval, the better.

Related Posts:

- Learn To Sail

- Mobile Apps

- Online Courses

- Upcoming Courses

- Sailor Resources

- ASA Log Book

- Bite Sized Lessons

- Knots Made Easy

- Catamaran Challenge

- Sailing Vacations

- Sailing Cruises

- Charter Resources

- International Proficiency Certificate

- Find A Charter

- All Articles

- Sailing Tips

- Sailing Terms

- Destinations

- Environmental

- Initiatives

- Instructor Resources

- Become An Instructor

- Become An ASA School

- Member / Instructor Login

- Affiliate Login

Need Current Inventory and Pricing?

206 284 1947

CHAT WITH US

Blog & News

Deep Dive , Videos

Man Overboard (MOB) Drill

Survival suits on! The crew of the Erla-N takes us along on their man overboard drill! Watch as they practice signaling, marking the location, turning the vessel, preparing a rescue swimmer, deploying a sling, and using the boat’s hydraulic system to lift the MOB and rescue swimmer. Brrrr!

Watch: Erla-N 2021 Man Overboard Drill

What is a Man Overboard Drill?

Man overboard (MOB) drills are a critical element of vessel safety and are designed to prepare the crew to jump into action quickly in the event of a crew member falling overboard. The drills ensure that everyone on deck knows best practices and has rehearsed their assigned role. In the icy waters of the Bering Sea, every second counts and preparedness saves critical seconds and minutes in the rescue effort.

What are the Typical Steps in a Man Overboard Drill?

- Wear personal flotation devices : wearing PFDs dramatically reduces deaths associated with falls into cold water.

- Sound the alarm (signaling) : the crew yells “Man overboard!!” to alert the captain, crew, and nearby vessels that there is a man overboard (MOB).

- Communicate position of MOB: post a lookout to continually point at the victim, track their location, and keep visual contact with the MOB throughout the recovery effort.

- Mark the MOB location and deploy flotation devices : throw in buoys and life rings and input the spot into GPS as well.

- Turn the vessel : return to the location where the crewman went into the water.

- Prepare a rescue swimmer: help the rescue crewmen get into an immersion suit with a detachable tether.

- Carefully approach the MOB : continue to maintain visual contract, keeping the boat at a safe distance depending on conditions.

- Deploy a rescue device : throw a life ring, lower a sling, ladder, or other boarding devices to help the MOB get back over the rail.

- Use a hauler: use a hydraulic hauler to help lift the MOB out of the water.

- Get help: If necessary, alert the Coast Guard to assist with the rescue or to provide medical attention to the victim.

What should You Do to Survive a Fall into Cold Water?

To help better understand the effects of cold-water immersion on the body, Dr. Giesbriecht (also known as “Dr. Popsicle”), developed the 1-10-1 principle .

- 1 Minute to get your breathing under control

- 10 Minutes of meaningful movement

- 1 hour before you become unconscious due to hypothermia

Due to the cold shock response, the initial fall into cold water can literally take your breath away. To survive these first few minutes, it is critical to stay calm, avoid panic, and use the first minute in the water to control your breathing. To prevent the hyperventilation that is common with a fall into cold water, breath out through pursed lips. Over the next 10 minutes, you will begin to lose muscle control due to cold incapacitation. It is important to use this time to plan and act before you are unable to do so. Get as much of your body out of the water as possible and keep your head above water with a floatation device if available. It generally will take about an hour before you become unconscious due to hypothermia.

What is an Immersion Suit?

The youngest member of the F/V Erla-N demonstrates how to don an immersion suit quickly: Immersion Suit Drill

Sometimes called a survival suit, an immersion suit is a waterproof dry suit that offers protection for commercial fisherman in the case of assisting in a rescue or needing to abandon their vessel while at sea. Donned in the case of an emergency, the suits typically includes an inflatable pillow that helps to keep the wearer’s head above water as well as other features that improve survival and rescue odds.

Why are Personal Flotation Devices (PFD) So Important?

Being able to stay afloat is critical to being able to survive a fall overboard. This is particularly true in cold water conditions where cold incapacitation (the loss of the ability to coordinate the movements needed to swim) generally leads to death before hypothermia. Wearing a life jacket or other personal flotation device allows the victim to stay afloat long after cold incapacitation has set in. This additional time is often the critical factor in rescue.

Man Overboard Drill and Cold Water Safety Resources:

- Video: “Man Overboard Prevention and Recovery”

- The CDC has prepared an excellent overview on preventing and reacting to falls overboard: Commercial Fishing Safety: Falls Overboard

- Cold Water Safety in Alaska

- Video: 1-10-1 Cold Water Principle

- US Army Tips for Surviving a Fall into Cold Water

Join the Crew!

Subscribe to Keyport’s YouTube Channel or follow us on Instagram for to see future man overboard drills and dispatches from the Golden King crab fishing grounds.

SUBSCRIBE TO NEWS & PROMOTIONS

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and promotions.

Success! Please Check Inbox For Confirmation Email.

Home News Man Overboard Recovery Procedure

Man Overboard Recovery Procedure

Written by Peter Isler, with additional contributions by Chuck Hawley and Michael Jacobs

“Man Overboard” is probably the third most famous nautical hail, after “Land Ho” and “Thar She Blows,” but it is by far the most serious and potentially life threatening of the three.

Man Overboard Rescue Procedure

Although we should keep in mind that every situation is different, man overboard procedures are often broken down into the following areas:

- Initial Reaction on Board

- Safety Turning the Boat Around and Returning to the ‘Person in the Water’ (PIW) (though I prefer the term “swimmer”)

- Approaching and Rescuing the PIW

1. Initial Reaction on Board

The first priority is to provide the victim with additional flotation to increase his or her odds of surviving until the boat returns. Be sure to also “litter the water” with any other floating paraphernalia that will increase visibility of the location, making it easier to find the PIW. From the simple speed, time, and distance equation, we know that time is critical when it comes to deploying any sort of safety or flotation gear if we want to be within dog paddling distance. This requires proper preparation and training so that the right equipment is easily available and deployable by any/every member of the crew.

Concurrently, the entire crew must be notified with that bone-chilling hail so the wheels of recovery can begin turning. Meanwhile, the person who first sees the PIW in the water must maintain a laser-like focus on his or her location in the water and continually point out that position to the helmsperson. It’s the luck of the draw when it comes to the roles being played on board. Although your crew should have default “emergency” positions, a man overboard will alter this because at least one crew is gone from the boat, while another is doing his or her best Superman impersonation to see through the waves and keep the PIW in sight. Short-handed crews have an even bigger challenge in a man overboard situation with perhaps half the crew missing.

Other high priority steps include:

- Save a GPS location to facilitate returning to the scene. If your victim is wearing and has activated an AIS-based personal locator beacon, he or she will be easier to find. Before a man overboard emergency occurs, make sure every member of the crew knows how to operate the hardware (GPS/computer) to navigate back to the AIS beacon and the GPS’ man overboard waypoint. Ideally, one of the items your crew “litters” into the water will be a floating AIS locator with a sea anchor.

- Call for help. Any man overboard situation is life threatening, so there is cause for issuing a “Mayday,” or at the very least, “Pan Pan” on the VHF to get nearby boats to your team. The importance of this step must be weighed with the actual situation (e.g., it’s blowing 3 knots and you are at anchor in the Virgin Island with the swim ladder set over the side) and how much it will impact/slow down the crew’s ability to turn the boat around as soon as possible.

- Position the crew to turn the boat around. Ideally, this will follow the procedures that you have determined are ideal for your boat in the current conditions and that you have practiced with your crew.

- Immediately turn the boat into the wind, if appropriate for your boat and conditions, then tack, and stop/slow the boat. This is the first stage of the “Quick Stop” method that revolutionized sailing’s “science” of man overboard a few decades ago. The logic was indisputable: the closer you keep the boat to the victim, the better the odds of a swift and successful recovery. Today, the Quick Stop remains a valuable rescue option for most boats, but like so many of the possible return and recovery techniques, it has its time and place. It may be exactly the right approach for our 40-foot displacement sloop on the way to the South Pacific, but may not work on a boat with different handling characteristics. For example, a 60-foot racing sloop blasting downwind under spinnaker, a rapid round up could cause significant damage that inhibits the boat’s capability to return to the victim. It also risks throwing more crew overboard in the process. Once again, as in any safety-related emergency, its is important to be flexible. Well before any possible MOB, accurately assess the best way to rescue a PIW overboard as swiftly and safely as possible. Seamanship, experience, sound judgement, and thorough training all increase your odds of success.

Every step of the recovery benefits from practice, but this first “reaction” stage is perhaps the most crucial. A real emergency is not the time to figure out where the “launch” button is on the man overboard gear, or how to best organize the remaining crew to safely turn the boat around. Practice safety drills as a team before you need to act.

2. Safely Turning the Boat Around and Returning to the PIW

The Quick Stop method highlights the ultimate goal of man overboard recovery: stay as near to the swimmer as possible. But you have to do this maneuver safely so that you can successfully complete the rescue. Every situation is different depending on the boat, which sails are set, the crew size and experience, and the conditions.

Recently, I attended a US Sailing Safety at Sea Course at the US Naval Academy and watched the midshipsmen demonstrate some of the overboard recovery variations aboard the Academy’s 44-foot sloops. Conditions were ideal: the water was smooth, the winds were light, and the victim was a Navy diver in full wet suit. But it was still impressive watching the crews perform their rescue swift fashion. Clearly, they had practiced and their demonstration went according to plan. Even as I mentally critiqued the well-rehearsed and simplified presentation, I had to admit, these sailors were pretty darn good – especially the 110-pound female midshipsman who singlehandedly steered her 44-foot sloop back to the diver, secured the sails, stopped the boat, and hauled him back on deck with the aid of a block and tackle system and a Lifesling harness. I’d want her aboard my boat if I fell over. Sure, the degree of difficulty increases exponentially when you throw in heaving ocean swells, strong winds, and the element of surprise, but I’d rather go overboard on a boat where the crew had done a ton of recovery training – even if it was only in smooth water and light air.

The bottom line of turning the boat around is that it must be done as swiftly as practical (time is the enemy of the PIW) and must be done safely so that the crew can efficiently shift into rescue mode. There will be some trade-offs involved, e.g., making an out of control Quick Stop vs. a controlled dousing of the big sails – and the driver/skipper must make these critical decisions. What sails (if any) should be left flying? Should the engine be employed? And if so, are all the lines clear and out of the water so they don’t foul the prop? When can we safely tack the boat? Are the conditions safe for us to jibe the boat? A strong and well-honed chain of command can help in these critical decisions, but remember the “x-factor” of a man overboard situation: the skipper could be the swimmer!

3. Approaching and Recovering the PIW

The priorities in this stage of the procedure are:

- Find the PIW. This can be extremely difficult and time consuming – and time is not the friend of the victim. If it is daylight and the conditions are mild; if the victim is healthy, wearing a life jacket, blowing a whistle, wearing or floating near an AIS-transmitting locator, flashing a light, and has made contact with the boat’s man overboard gear; and if the boat has a good man overboard position to navigate back to – then the odds are pretty good that you will find him or her, even if it takes a few minutes to get the boat safely turned around. But that’s a lot of “ifs” and this highlights why having the boat and crew prepared for a man overboard incident is so important. Locating the PIW can be extremely difficult. So, that call you made on the VHF to rally immediate support from nearby boats can be a life-saving step in certain situations.

- Approach carefully and at a controllable speed. The close reach is by far and away the safest point of sail to make the approach because of the ease at which speed can be increased or decreased without making course changes. Try picking up a mooring on any other point of sail and you will soon agree.

- Make contact with the PIW. This doesn’t mean smashing the victim with your hull or chopping him or her up with your propeller. It means making a connection, most likely by rope and possibly by a Lifesling or other lifting/flotation device.

- Retrieve the PIW and get him or her safely on board. There are a number of potential methods that vary in their efficacy depending on the boat, conditions, crew size and strength, condition of the PIW, and equipment available.

- Apply appropriate care for possible near drowning, hypothermia, or any other injuries.

At this point in your study of man overboard procedure, I highly recommend a mental reality check. I’ve written and edited a number of books and articles describing the various “classic” recovery patterns and methods, including the aforementioned. Quick Stop and the venerable “figure eight” pattern. It all seems so doable on paper.

But let’s put ourselves in the shoes of a full crew on one of the US Naval Academy’s 44-foot sloops, sailing in 35-knot winds and hail during a thunderstorm. You must quickly revert to good seamanship, simple and basic sailing tactics – no jibes in 35 knots! And you will have your hands full even getting close to the victim as the keel loses grip and the boat blows sideways to low speed. There’s no way you can heave a line any distance upwind, but it’s so rough that you don’t want to approach within a quarter of a boat length to windward of the PIW for fear of smashing him or her to bits as the bow bucks in the waves. Again, this is where practice, good seamanship, and sailing experience are essential to stand any chance of recovering the PIW.

In extreme conditions or when shorthanded, the “waterski tow rope” method of making contact with the victim is invaluable. A few decades ago, the Sailing Foundation of Seattle developed the Lifesling device and its unique method of PIW recovery. Although the hardware has been refined over the years, it remains an icon in man overboard training with a long history of success, especially assisting small people in rescuing large people on boats of all sizes and types. The Lifesling employs the same method the driver of a water ski boat uses to return the tow rope to a fallen skier for another try. It involves circling safely and slowly around the PIW until they grab the floating tow rope and work their way to the floating harness that can double as a lifting sling – pretty nifty.

But if the PIW is injured or if it’s too windy to jibe (a sailboat can’t circle without doing a jibe), you will have to adjust your tactics. You may even break another “rule” of man overboard and send a second crew member into the water (firmly tethered to the boat) to help the victim. (Editor’s note: Not recommended unless the victim has serious injuries or is a child.)

Do I sound like a broken record yet? It’s all too easy to discuss man overboard theory and practice in a vacuum, extolling the virtues of a certain piece of equipment and/or sailing technique. But every situation is unique. In all likelihood, the crew will not be able to follow a perfect, cookie cutter method. They will be forced to adapt and make important decisions very quickly under pressure. This is where training, practice, good seamanship, and boat sense all play a crucial role.

In summary, read books and take courses. Go to the chandlery and look at the latest equipment. Get your crew together and practice, practice, practice. Then cross your fingers you’ll never have to learn whether you have the right stuff to save a life because everybody on the crew remembers that lesson their mother taught them: always stay with the boat!

This resource is provided by the US Sailing Safety at Sea Committee. Read the entire chapter on Weather Forecasting and Waves .

Learn more about US Sailing Safety at Sea Seminars in your area.

Copyright ©2018-2024 United States Sailing Association. All rights reserved. US Sailing is a 501(c)3 organization. Website designed & developed by Design Principles, Inc. -->

- New Sailboats

- Sailboats 21-30ft

- Sailboats 31-35ft

- Sailboats 36-40ft

- Sailboats Over 40ft

- Sailboats Under 21feet

- used_sailboats

- Apps and Computer Programs

- Communications

- Fishfinders

- Handheld Electronics

- Plotters MFDS Rradar

- Wind, Speed & Depth Instruments

- Anchoring Mooring

- Running Rigging

- Sails Canvas

- Standing Rigging

- Diesel Engines

- Off Grid Energy

- Cleaning Waxing

- DIY Projects

- Repair, Tools & Materials

- Spare Parts

- Tools & Gadgets

- Cabin Comfort

- Ventilation

- Footwear Apparel

- Foul Weather Gear

- Mailport & PS Advisor

- Inside Practical Sailor Blog

- Activate My Web Access

- Reset Password

- Pay My Bill

- Customer Service

- Free Newsletter

- Give a Gift

Ericson 34-2 Finds Sweet Spot

How to Sell Your Boat

Cal 2-46: A Venerable Lapworth Design Brought Up to Date

Rhumb Lines: Show Highlights from Annapolis

Leaping Into Lithium

The Importance of Sea State in Weather Planning

Do-it-yourself Electrical System Survey and Inspection

Install a Standalone Sounder Without Drilling

When Should We Retire Dyneema Stays and Running Rigging?

Rethinking MOB Prevention

Top-notch Wind Indicators

The Everlasting Multihull Trampoline

Check Your Shorepower System for Hidden Dangers

DIY survey of boat solar and wind turbine systems

What’s Involved in Setting Up a Lithium Battery System?

The Scraper-only Approach to Bottom Paint Removal

Can You Recoat Dyneema?

Gonytia Hot Knife Proves its Mettle

How to Handle the Head

The Day Sailor’s First-Aid Kit

Choosing and Securing Seat Cushions

Cockpit Drains on Race Boats

Re-sealing the Seams on Waterproof Fabrics

Safer Sailing: Add Leg Loops to Your Harness

Waxing and Polishing Your Boat

Reducing Engine Room Noise

Tricks and Tips to Forming Do-it-yourself Rigging Terminals

Marine Toilet Maintenance Tips

Learning to Live with Plastic Boat Bits

- Safety & Seamanship

- Lifejackets Harnesses

Man-Overboard Retrieval Techniques

What is the best mob rescue tactic for your boat and crew.

The term Man Overboard (MOB) has been caught in the tide of political correctness, and terminology like Crew Overboard (COB) and Person in the Water (PIW), the U.S. Coast Guards latest designator, have changed safety semantics. Regardless of the phraseology, it remains a cry that every sailor hopes to never hear.

Practical Sailor has looked at this important topic on several occasions over the past few years. There was a comprehensive two-part report on gear and tactics in November 2005 and January 2006. In May 2006 and April 2007 we looked at throwable rescue devices. And in May 2008, Practical Sailor Technical Editor and marine safety expert Ralph Naranjo compared a variety of electronic man-overboard becons and alarms.

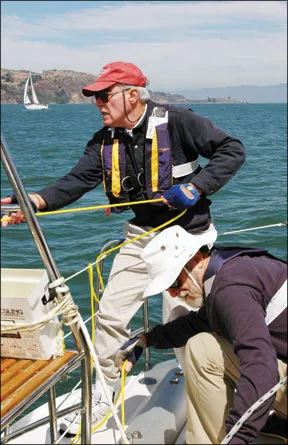

Photos by Ralph Naranjo

This update focuses on a key element to a safe recovery: seamanship. Our findings-some of which contradict or amend current thought on the subject-are based on analysis of a series of on-the-water drills on Chesapeake Bay. The drills were carried out earlier this year under the direction U.S. Naval Academy Sailing Master Dan Rugg and with the participation of the Philadelphia Sailing Club. Naranjo was invited to observe.

By taking a close look at how the crews from the Philadelphia Sailing Club members (aboard a J/37, representing mainstream racer/cruisers) and midshipmen from the U.S. Naval Academy (aboard the McCurdy performance-oriented offshore sailors) react to overboard situations, Practical Sailor hoped to develop some valuable insight into what works most effectively in any given condition and how to optimize a crews chances for success.

Anatomy of a Recovery

The wide range of variables that can come into play cannot be overstated. It is clear that factors ranging from crew skill and size to the vessels behavior under different sea states affect the challenges involved in a rescue and define the right maneuver to use. However, some common denominators stand out.

First and foremost, the success of any man-overboard drill will depend on a clear chain of command. This may sound militaristic, but in a crisis, the most capable person needs to be making the calls. Naturally, the person at the helm at the time of the incident must be able to carry out the initial steps in the maneuver, at least until the skipper or watch captain decides whether to step in. Regardless of who is at the helm, command resides in one person, and its their job to clearly direct the rescue process.

Providing a victim with flotation is part of the first phase of every overboard response, even if the victim is wearing a life jacket. The additional floating cushions and other throwable rescue gear can also make the victim easier to spot. Marking the location with an MOB pole, light and drogue-equipped horseshoe, or a man overboard module-type device (MOM) is also an imperative part of the early response.

This is one point where Practical Sailor s view diverges from some other accepted guidance. U.S. Sailing, the governing body of sailboat racing in the U.S., advises that such poles and spars be reserved for later deployment. In Appendix D of the ISAF Special Regulations that govern offshore racing, U.S. Sailing prescribes: “The pole (strobe and dan buoy) is saved to put on top of the victim in case the initial maneuver is unsuccessful.” This blind assumption that the first maneuver will bring the crew closer to the victim is a leap of faith thats unwarranted and dangerous, in our view. In numerous incidents, the initial sighting of the victim being left astern was the last sighting.

Man Overboard Modules

Our two-part series in 2005-2006 delved into the pros and cons of the MOM 9 (man-overboard module), a popular, self-contained, inflatable pole and flotation device that can be deployed to a person in the water. One advantage is the ease with which it can be released. However, during independent testing in 2005, a unit repacked by an approved vendor opened with its lines snarled around the vertical spar, causing it to kink in half. The ease and speed with which a MOM can be deployed outweighs the snarl issue, and it is a viable option, especially for shorthanded crews. Deploying a MOM or similar pole/strobe/flotation combo should be a part of any overboard routine. Since it is expensive to rearm and repack the MOM 9, mock deployment can be simulated with a faux pull-handle taped to the top of the MOM.

The Right Stuff

Each crew member should be able to execute a recovery maneuver. Naturally, it makes most sense to have the best helmsperson on tiller, the person with Chuck Yeagers 20/10 vision acting as spotter, and the agile ex-lifeguard ready to help the victim, in or out of the water. But the situation seldom sets up so conveniently, so role-playing must remain fluid. For example, the person closest to the overboard gear should launch it, the person nearest the GPS hits the MOB button and shouts that the position has been recorded. Scribbling a lat/lon position in the log or on the margin of a chart is also good practice.

Perhaps the most important task of all in a man-overboard recovery is the job of continually spotting the person in the water. If there are enough hands on board, the designated “spotter” should concentrate only on this task. In this high-tech age, spotting can be assisted by night-vision equipment or image-stabilized binoculars. An infrared-reading thermal imaging system can also help in locating a warm spot on a cooler sea surface, although these are extremely expensive. (FLIR, the company whose fixed thermal imaging camera we reviewed in June 2008 recently unveiled a portable unit for $3,000.) These aids can be used alone or in conjunction with one of the signal-beaming pendants like the Mobi-Lert (www.mobilarm.com) that Practical Sailor reviewed in May 2008. New 406MHz personal locator beacons (PLBs) are also a promising technology. Ultimately, the best fix of a person in the water remains a visual one, and the crew that stays closer to the victim has a much better chance of completing a successful recovery.

Recovery Maneuvers

At this point, all on board are up to speed on whats happened and the helmsperson has begun the recovery maneuver. The crew has been assigned key roles, and each member knows what must be done. The ultimate goal of all under-sail recoveries is a well-aligned close reach that brings the boat back to the victim just as the boat speed drops to zero. Racers have an advantage: the more trained hands working together, the better the chances of success. Cruisers face a serious handicap: too many tasks and too few hands. Success of the shorthanded crew will rely greatly on the speed and coordination of the response, as well as close familiarity with the various rescue maneuvers. Another key component is the type of recovery gear onboard. Illustrations and capsule summaries of the most common rescue maneuvers appear on the facing page, but the following observations that emerged from the Chesapeake Bay exercises should also be taken into consideration.

For the shorthanded sailer, the challenge lies in steering the vessel while keeping the victim in sight, and at the same time coping with the sails, recording the MOBs position, and other steps in the routine. In such cases, the Lifesling can be a valuable aid, helping to streamline the recovery process. Profiled in our 2005-2006 report, this horseshoe-shaped flotation device can be deployed early in the maneuver. Unlike the life ring, spar, or dan buoy deployed immediately, it stays connected to the boat by a safety line.

The Lifesling-assisted rescue allows for less-precise boathandling. It can be used in tack-only type maneuvers (Figure 8, Fast Return, Deep Beam Reach) or in those that incorporate a jibe (Quick Stop), with one important proviso: Although the Lifesling2 instructions say “circle the victim until contact is made,” this is misleading. As any waterskier knows, a circular pattern is not an effective way to get the line into the hands of the skier. To bring the rescue line attached to the Lifesling into the hands of the victim, a button-hook approach is much preferred. During testing, the optimum Lifesling delivery always included passing closely by the victim prior to a sharp turn on the final approach. A wide turn that leaves the victim in the center of circle-as many published illustrations suggest-sharply reduces the chance of success.

The Lifeslings floating poly line should not be coiled into its bag. Beginning at the point furthest from the float, the line should be shoved to the bottom of the container. If a snarl occurs during deployment, it usually can be coaxed out with a couple of tugs. If a tack-to-recover type maneuver is used, the Lifesling is not deployed until the tack has been completed and the return to the victim begun.

If the Lifesling is deployed using a modified Quick Stop (Figure 1, page 8), theres a jibe involved and reducing speed becomes imperative. Center the mainsail early, and as the boat bears off, furl or drop the jib. Reducing sail area is key, because once the victim slips on the horseshoe float, dragging them through the water can be fatal. If the jib has already been furled or dropped, turning the boat to windward and dropping the mainsail halyard will stop the boat in its tracks. Once the boat is stopped, the victim can be hauled or winched in, and a ladder, swim step, parbuckle, or halyard can be used to bring them back aboard.

The fully-crewed race boat faces a very different challenge. Theres an ample number of able crew available, but the boat will likely need to be quickly slowed down prior to any rescue maneuver. This is especially true of a modern lightweight racer that simply can’t shift from a planing reach to a Quick Stop turn in a boat length. Consequently, the first part of their recovery maneuver is a counter-intuitive sprint away from the victim. Because of this inevitable and distressing separation, the appeal of locator beacons and direction-finding equipment has gained ground among racers, as has harness and jackline use.

Power Assist

No extra points are given for rescuing a victim under sail. Its true that a spinning propeller is dangerous, but far more lethal is the boat that never gets back to the person in the water. Starting the engine, keeping it in neutral, and after checking for lines in the water, using it as needed to help control the final approach is prudent seamanship. In some shorthanded scenarios, a Lifesling rescue under power may prove to be the best option available. Naturally, the engine needs to be in neutral as the final approach to the victim is made, and as soon as contact is made, the engine should be shut off.

The Final Approach

All too often, in the rush to quickly return to the victim, the boat sails right by the person in the water at 3 knots or more, making rescue both dangerous and unlikely. The helmsperson and sailhandlers work in conjunction to slow down during the final close reach approach to the victim, arriving with about a half-knot of boat speed. On the ocean, the pitching moment can kill forward motion too soon. Conversely, in flat water, the helmsperson must start slowing down much sooner. This is why practice should take place in all conditions in which the vessel will sail. Ideally, a sailboat completes a rescue maneuver by nudging alongside the person in the water, a line secures the contact, and he or she scurries aboard on a swim step or ladder. More often, however, a rescue quoit, life ring, or boat hook is needed to make contact. A thrown Lifesling or life ring can cover short distances, but if neither is available or the distance is greater, a rescue quoit like the Marsars 2-in-1 (reviewed in May 2006), can be put into action. Weighted at the end with a floating ball, a rescue quoit is preferred over a one-shot throw rope for this purpose because it can be more easily re-deployed. Regardless of what device you use to make contact, all crewmembers should practice its use.

Civilian Sailors and Midshipmen

Training makes a big difference, and after observing both the USNA midshipmen and members of the Philadelphia Sailing Club execute crew-recovery maneuvers, some important observations can be made.

Both groups quickly learned to cover the requisite aspects (shout, throw, steer, fix) of the recovery drill. The biggest common problem was simultaneously keeping track of vessel movement, true wind direction, and the person in the water. Many misjudged the true wind, and attempted to return to the victim on a deep reach, making slowing down impossible. It was interesting to note how quickly some of the sailing club members adjusted to the J/37s responsive helm. Its ability to turn on a dime surprised sailors accustomed to more traditional sailboats. The bottom line: It takes a familiarity with close-quarters boathandling to place the boat where it belongs in MOB maneuvers.

Another important variable noted was leadership. The best helmsmen displayed both an ability to effectively steer and lead, informing the crew what would happen next, and who should have a lead role in each aspect of the recovery.

One of the key issues stressed by USNAs Rugg was that the practice conditions were optimum, in broad daylight, flat seas, and fair weather. He also noted that because the participants knew the exercise was a drill, they didnt experience the usual shock and stress. He emphasized that only through periodic training with a regular crew can you be fully prepared for an actual event.

The Philadelphia Sailing Club members found that the Quick Stop maneuver-while suited to youthful midshipmen at the Naval Academy and appropriate for many “round-the-buoys” sailors-is not always the best bet for everyone. On one hand, it keeps the crew closer to the person in the water. But it requires an abrupt stop, a jibe, and can be complicated by double-digit speeds, spinnakers and running rigging like backstays and preventers. Shorthanded mom-and-pop crews are certainly better off with a Lifesling. Regardless of the recovery process chosen, its vital that all crew members are on the same page and have spent time training together with a specific maneuver.

Conclusions

We went into this project hoping to find a recovery procedure that could be given a “one size fits all” nod of approval. U.S. Sailing favors the Quick Stop. For their constituency, sailors aboard fully-crewed, highly maneuverable race boats, it makes a lot of sense. But even the pro racer sees problems when their boat speed approaches that of a planing Boston Whaler. Under such conditions the prospect of an abrupt turn into the wind spells big trouble.

The mom-and-pop crew cringe at the thought of the quick tack and impending jibe just when their crew number has been reduced by half. Add to this the challenge of coming alongside and nimbly getting hold of your partner before the bow falls off, and the prospect of being lost at sea turns into the potential of being drowned by the boat. In short, the Quick Stop has its merits, but it does not rise to the “one size fits all” rescue technique. Thats why U.S. Sailings Training Committee includes Reach-Tack-Return (Figure 8) maneuvers and under-power Lifesling approaches in their textbooks.

The Figure 8 and its tack-to-return cousins eliminate the jibe and are easier to accomplish, especially in heavier winds, but there are several inherent pitfalls. The most significant is the initial necessity to sail away from the victim. Its tough enough to minimize this dangerous separation in optimal conditions. However, in 20-knot winds at 0300, keeping the separation distance to just a few boat lengths is impossible. A two-minute spinnaker takedown can leave a victim a quarter-mile away.

Each iteration refers to sailing off just a couple of boat lengths, but in real life, a windy, dark, storm-tossed night at sea can tally up more boat lengths of separation than desired. Losing sight of the person in the water is a big deal and the helmsperson must be ready to execute the tack in a timely fashion.

A key moment during the “tack-only” maneuvers occurs when the vessel is head-to-wind, midway through the tack, and the victims location is noted. At this point, the helmsperson can carefully note the true wind. The most common problem in all types of recoveries is found in the final approach when a helmsperson has not maneuvered far enough downwind and must approach on a beam reach that eliminates the ability to de-power the boat.

The Fast Return and the Deep Beam Reach, with all sails up, may be fine in lighter winds and flat water, but not in heavier conditions. This is why Volvo Ocean racers and many other high-velocity ocean racing programs are looking closely at electronic beacon technology.

Vessel design plays a big role. The long keel, high directional stability of a classic cruiser means it wont spin on a dime, nor will it bleed off boat speed quickly. The deep high-aspect ratio foils of a modern race boat deliver the nimbleness needed for the final approach, and can accelerate and decelerate quickly. However, the easy-to-steer race boat may have luff-tape sails that are hard to douse and harder to keep from going over the side. The bottom line is that each boat differs and how a rescue maneuver is implemented must take underbody design and deck layout into consideration.

Ultimately, sailors need to test each of the alternatives, not just on a light-air Sunday afternoon, but at sea in varying conditions and at night. A fender lashed to a milk crate with a strobe tethered to the makeshift Oscar can play the role of a person in the water. After these sea trials, settle on the technique that best fits the handling characteristics of your boat and the skills of your crew. Let each person take a turn at different responsibilities, except of course, the “victim” who is sent below to think about what it would be like in the water. Finally, recognize that preventing an overboard incident is the only alternative that comes with a back-on-board guarantee.

- Tips & Techniques

- Practical Sailor: Skill Guide

- Crew Overboard Resources Online

- View PDF Format

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

How Can I Keep My Kids Safe Onboard?

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Log in to leave a comment

Latest Videos

40-Footer Boat Tours – With Some Big Surprises! | Boat Tour

Electrical Do’s and Don’ts

Bahamas Travel Advisory: Cause for Concern?

Island Packet 370: What You Should Know | Boat Review

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- Online Account Activation

- Privacy Manager

- Man Overboard

Man overboard

The exclamation ‘man overboard’ refers to a crew member or a passenger falling into the water and needing immediate rescue.

.jpg?w=100%25&hash=CAEFE30E68555953AC8BF254DDB56F03)

Research by the Maritime Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) has shown that crews have, on average, less than 11 minutes to recover a crewmate who has fallen overboard into cold water before the victim becomes unresponsive. This time decreases as the water becomes colder, or the sea state rougher. In some cases, crew had just four or five minutes to coordinate a complex recovery under extreme pressure. Sadly more than 40% of man overboard occurrences reported to the MAIB between 2015 and 2023, tragically led to a fatality. A startling reminder of the importance of getting all your crew trained and having a well-practised plan. Read on for more information about prevention, and how to prepare for a man overboard occurrence.

Man overboard prevention

Before setting off, ensure all crew receive a thorough safety briefing. This should include, moving along the high side of the vessel, keeping one hand for yourself and one for the boat, and clipping on . When clipping on, use a tether that’s the right length and secured to a purpose made strong point or jackstay.

If conditions deteriorate, reef early or slow down if on a power or motorboat. Consider directing crew who are less experienced or agile, to remain in safer areas such as the cockpit or cabin.

Provide clear directions and guidance to those who may need to venture out of the cockpit for hoists, drops, anchoring, and other tasks.

Man overboard whilst attached

A safety line offers the advantage of keeping a casualty attached to a vessel. This avoids the need for a search and any potentially challenging manoeuvres to reach the man overboard. However, being attached does come with its own hazards.

Where a casualty is attached to the boat and in the water, the priority must be to stop the boat altogether. Any movement through the water, even at very low speed, must be avoided as it risks forcing water into the casualty’s lungs.

If unable to stop the boat or remove the casualty from the water, carefully consider cutting the tether and coming back to them with the boat at a standstill.

Man overboard unattached

In this situation, time is of the essence. In water of 15 degrees Celsius or less there is a risk of cold water shock , which can result in cardiac arrest or other medical issues.

When faced with a man overboard situation in which the casualty is unattached, the first step is raising the alarm to the crew.

Appoint a spotter to maintain visual contact with the casualty and deploy a danbuoy or life rings to mark the spot and provide buoyancy.

Press the man overboard button on the plotter to provide a last known position and issue a MAYDAY or DSC Alert. Try to stop the boat or reduce your speed to avoid further man overboard situations.

Prepare your recovery equipment and reassure the casualty that you will be returning to them.

Think through your approach to reach the casualty. Aim to position your vessel upwind of them, so that as you slow down the vessel is blown towards them. Always ensure the crew is properly briefed on your next steps during recovery.

Alongside and recovery

Once alongside the casualty, it’s important to ensure that engines are left in neutral or switched off. Whether or not you switch off the engine depends on weather conditions, your vessel, or a variety of other factors. Regardless, risk to the casualty from a spinning propellor must be avoided at all costs.

If the casualty is conscious and can assist in their recovery, throw a heaving line to help recover them. A scramble net, rescue ladder, boarding ladder, or swim platform on the stern (calm conditions only) can be useful in helping to recover a man overboard.

Depending on your vessel, you can use a halyard, block and tackle from the boom, dedicated lifting device or a davit coupled with a lifting strop. Recovery can also be aided with the inflation of a life raft or over the side of a RIB or tender.

Unconscious casualty

Where the casualty is unconscious, the recovery becomes far more challenging. A crew member will need to secure a lifting device to the casualty’s lifejacket or harness.

In this situation, other crew members will be at risk reaching overboard or being lowered towards the casualty to make contact. This is an extremely challenging situation for a skipper and crew, involving decisions that should not be made lightly.

When lifting a casualty onboard, they should remain in a horizontal position to avoid the potential medical complications caused by hydrostatic squeeze. However, drowning remains the primary risk, therefore recovery onboard is the priority.

Onboard casualty management

Once the casualty is onboard, they need to be carefully monitored. First aid needs to be provided and for non-breathing or unconscious casualties all the appropriate steps should be taken.

Conscious casualties or those who have recovered themselves are at risk of shock, hypothermia, secondary drowning, and injuries incurred during their fall or recovery.

Wet clothing should be removed, and the casualty should be warmed, carefully monitored, and transported to a medical facility for review.

Get trained

It’s important to prepare for the unexpected. If the man overboard is the skipper, is anyone else onboard properly trained to take control and manage the recovery?

Anticipating what could go wrong and then practicing is the best form of preparation to avoid emergencies and keep you and your crew safe.

However, if you lack the confidence to develop these skills yourself, RYA specialist training courses can equip you with the skills and knowledge to save a life.

The RYA’s Helmsman , Competent Crew and Day Skipper courses are the perfect way to build your confidence and enhance your skills.

For more information on staying safe on the water, visit the RYA safety hub .

Man Overboard Recovery & Prevention

Man overboard fatalities are the second leading cause of death among commercial fishermen in the u.s. learn what to do in case of a man overboard incident., learn more....

Adapted from, Beating the Odds: A Guide to Commercial Fishing Safety, 7th Edition , Susan Clark Jensen and Jerry Dzugan, 2014

John had been fishing for almost 20 years, when in the middle of the night, 40 miles out from Long Island, he went out on deck alone at 3:30 a.m. to open a hatch on the deck of the lobster boat. A sudden slip and he found himself falling backward down the stern of the vessel and submerged in the 72° Atlantic Ocean. After a gulp of ocean, he surfaced, sputtered, and hollered at his boat with his two sleeping workmates warm and dry in their bunks. He watched his boat on autopilot steam away from him at 8 knots on a clear moonlit night with 5 foot seas. He wasn’t wearing a life jacket. Quickly John found out that his thick rubber boots would float.

He took them off, plunged them inverted in the water to make an air pocket in each, and put them under his armpits for flotation. Almost 12 hours later, shivering uncontrollably, he was spotted and rescued by a Coast Guard rescue helicopter, glad to have survived. (Paraphrased from “A Speck in the Sea,” The New York Times, Paul Tough, Jan. 2, 2014)

There is no denying it. Fishermen do end up overboard. Between 2000 and 2014, 39 percent of all commercial fishing deaths in the United States were due to falls overboard, according to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). You might never face this situation, but being prepared in case it does occur could save a life, perhaps your own. Of the 210 man overboard deaths between 2000 and 2014, not one person was wearing a PFD .

Before Anything Happens

Hold man overboard drills with a crewmember in a survival suit playing the part of the person in the water. The first drill can even be held in the harbor. You will need to devise a retrieval system; hauling someone on board is difficult and can result in injuries. Some forethought will allow you to come up with an effective system. Try a sling or horse collar used with a winch and boom, a net with floats, a commercial man overboard retrieval device, or a hatch cover and winch.

Make yourself warmer and more visible in the event you do fall overboard by wearing layers of wool or polypropylene clothing, and bright-colored rain gear or a PFD. Increase your chances of being rescued at night by putting reflective tape on your PFD, rain gear, hard hats, and anything else that might fall overboard. Reflective tape is a very cheap safety supply.

Whenever you are on deck, wear a PFD with a whistle or other signaling device.

Keep “one hand for the ship and one for yourself,” during all activities. (It is not a good idea to relieve yourself at the rail.)

Keep a throwable PFD—with a working light and reflective tape—handy to toss over as a marker in case someone does go overboard.

Use a buddy system on deck after dark, especially in rough seas.

Where practical, have bulwarks or safety rails of adequate height, and provide grab rails alongside or on top of the house.

Use nonskid deck coatings, and keep decks clear of slime, oil, jellyfish, and kelp.

Use safety lines and a PFD when clearing ice.

If you fish alone, consider using a kill switch that will shut off your engine if you fall overboard. Or you may want to use a harness with a safety line that would keep you attached to the boat if you go overboard.

Consider towing a skiff or knotted, floating line with a buoy on its end to provide a close target to grab or climb onto. If you use either of these methods, you must use floating line attached high up on the vessel, and be conscious of the possibility of the line getting fouled in the prop. Some fishermen believe in and use the skiff or floating line method, while others think they present more danger than they are worth. The choice is yours.

Consider purchasing one of several man overboard alarms on the market. Some of them also will shut off your engine so you have a chance to reach your vessel if you are alone, and one alerts other vessels in the area to your location.

Cold Water Survival Stages

Although it is hard to believe, the Gulf of Mexico in winter has water temperatures similar to the Gulf of Alaska in summer! Cold water can be found in most places in the United States depending on time of year. The four phases in cold water survival are: cold shock response, cold incapacitation, hypothermia, and post-rescue collapse.

Cold shock response (first 2 minutes). On entering cold water, the person will gasp involuntarily and start uncontrolled hyperventilation. If the head is under water the person will drown. Enter the water slowly if possible and it is ideal to have thermal protection. Also there is a danger of fainting and cardiac arrest.

Cold incapacitation (2-15 minutes). Local cooling of nerves and muscle fibers causes the inability to swim, so hold on to a floating object or the edge of the water (ice or shore). Thrashing around will cause increased heat loss and may lead to exhaustion and drowning. To delay the onset of hypothermia, use the HELP position or huddle with other people. Get out of the water entirely or as much as possible. A person who is hanging onto a boat and has no PFD should stay with the boat. A person who has a PFD should swim to shore if they think they can make it within 45 minutes and rescue is not likely in the next hour.

Hypothermia (at least 30 minutes to become unconscious). If the head goes under cold water, drowning will occur in about 30 minutes to 2 hours. If the head is above water because of a personal flotation device, cooling will lead to cardiac arrest and death in 90-180 minutes.