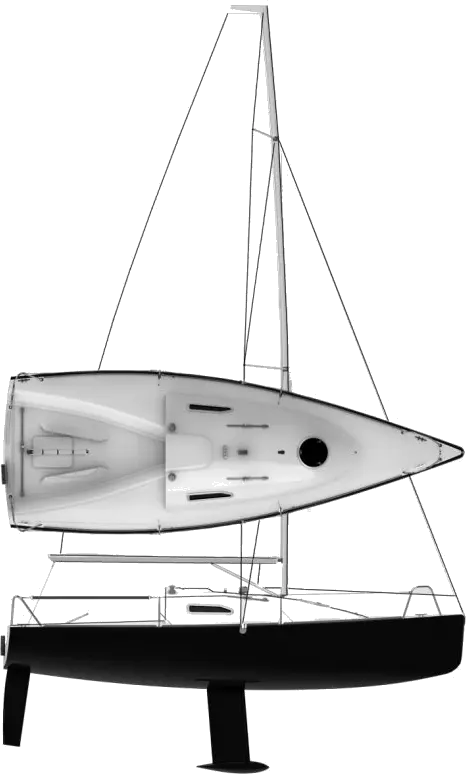

Review of Mantra 28

Basic specs..

The boat is typically equipped with an inboard Yanmar 1GM10 diesel engine.

The transmission is a saildrive.

The fuel tank has a capacity of 33 liters (8 US gallons, 7 imperial gallons).

Sailing characteristics

This section covers widely used rules of thumb to describe the sailing characteristics. Please note that even though the calculations are correct, the interpretation of the results might not be valid for extreme boats.

What is Capsize Screening Formula (CSF)?

The capsize screening value for Mantra 28 is 1.84, indicating that this boat could - if evaluated by this formula alone - be accepted to participate in ocean races.

Mantra 28 holds one CE certification:

What is Theoretical Maximum Hull Speed?

The theoretical maximal speed of a displacement boat of this length is 6.8 knots. The term "Theoretical Maximum Hull Speed" is widely used even though a boat can sail faster. The term shall be interpreted as above the theoretical speed a great additional power is necessary for a small gain in speed.

The immersion rate is defined as the weight required to sink the boat a certain level. The immersion rate for Mantra 28 is about 141 kg/cm, alternatively 790 lbs/inch. Meaning: if you load 141 kg cargo on the boat then it will sink 1 cm. Alternatively, if you load 790 lbs cargo on the boat it will sink 1 inch.

Sailing statistics

This section is statistical comparison with similar boats of the same category. The basis of the following statistical computations is our unique database with more than 26,000 different boat types and 350,000 data points.

What is Motion Comfort Ratio (MCR)?

What is L/B (Length Beam Ratio)?

What is Displacement Length Ratio?

Maintenance

If you need to renew parts of your running rig and is not quite sure of the dimensions, you may find the estimates computed below useful.

This section shown boat owner's changes, improvements, etc. Here you might find inspiration for your boat.

Do you have changes/improvements you would like to share? Upload a photo and describe what to look for.

We are always looking for new photos. If you can contribute with photos for Mantra 28 it would be a great help.

If you have any comments to the review, improvement suggestions, or the like, feel free to contact us . Criticism helps us to improve.

I want to get mails about Recently added "mantra 28" ads.

I agree with the Terms of use and Terms of Privacy .

Publication date

- Last 15 Days

- Most popular

- Most recent added

- Lower price

Price (min)

- 100.000 USD

- 125.000 USD

- 150.000 USD

- 175.000 USD

- 200.000 USD

- 225.000 USD

- 250.000 USD

- 275.000 USD

- 300.000 USD

- 350.000 USD

- 400.000 USD

- 450.000 USD

- 500.000 USD

- 600.000 USD

- 700.000 USD

- 800.000 USD

- 900.000 USD

- 1.000.000 USD

- 1.100.000 USD

- 1.300.000 USD

- 1.500.000 USD

- 1.700.000 USD

- 2.000.000 USD

- 2.500.000 USD

Price (max)

Hull Material

Length (min)

Length (max)

mantra 28 for sale

Mantra 28 (sailboat) for sale

Mantra 28 , Bj. 2004 im Kundenauftrag, sehr guter Zustand. Erste Hand. Umfangreich ausgestattet. Sehr sauber. Inneneinrichtung...

2024 Regent Royal 28 Dual Console Sport Triple Hull Pontoon

Pontoon boat.

New 2024 Regent Royal 28DC SB Sport Triple hull pontoon boat which is pre-rigged for Suzuki EFI 4-Stroke outboard engines up to a maximum of 300hp. Regent Pontoons...

Zodiac PRO Classic 750 Grey Boat Grey Hull, Max 20 Persons (BOAT ONLY)

Zodiac pro classic 750 grey boat grey hull, max 20 persons boat only.

Diving, fishing, underwater hunting, work, or pleasure, choose and compose the layout of your boat Depending on your program and your preferences: your PRO will...

Other classifieds according to your search criteria

Related Searches "mantra 28" :

The information we receive from advertisement sites may vary. Therefore, when you go to the listing site, you may not always find the same offer that you see on waa2.

- Add Your Listing

- Terms of Privacy

- Terms of use

- About

Popular Sailboat Models

- Bavaria Cruiser 46

- Fountaine Pajot Saona 47

- Beneteau Oceanis 45

- Beneteau 50

- Catalina 30

Popular Powerboat Models

- Sea Doo Speedster

- Sea Ray Sundancer 320

- Bayliner Vr5

- Beneteau Antares 11

- Malibu Wakesetter 23 Lsv

- Boston Whaler 170 Montauk

- Princess V65

- Jeanneau Nc 1095

Feedback! ▼

Waa2 login to your account, register for free, forgot password.

Would you also like to receive alerts for these other related searches?

aventura 28

dehler yachts 28

carver 28 santa cruz

luhrs 28 open fiberglass

Waa2 uses our own and third-party cookies to improve your user experience, enhance our services, and to analyze your browsing data in order to show you relevant advertisements. By continuing browsing please note you are accepting this policy. You are free to change the settings or get more information here >>> OK

- Choose the kind of boat Big boats Motor boats Rubber boats Sailing boats Sailing multihull boats

General Data

See also: boats for sale.

- Baruffaldi Baruffaldi P38

- Comar Yachts Comet 850

- Comet Comet 850

- Alpa 27 alpa 27

Overall length:

Waterline length:, maximum beam:, displacement:, straightening:, construction materials:, sail details mq, equipments:, transmission:, water tank:.

- Motorcycles

- Car of the Month

- Destinations

- Men’s Fashion

- Watch Collector

- Art & Collectibles

- Vacation Homes

- Celebrity Homes

- New Construction

- Home Design

- Electronics

- Fine Dining

- Baja Bay Club

- Costa Palmas

- Fairmont Doha

- Four Seasons Private Residences Dominican Republic at Tropicalia

- Reynolds Lake Oconee

- Scott Dunn Travel

- Wilson Audio

- 672 Wine Club

- Sports & Leisure

- Health & Wellness

- Best of the Best

- The Ultimate Gift Guide

Boat of the Week: This 185-Foot Sea-Cleaning Sailboat Collects up to 3 Tons of Ocean Garbage per Hour

The "manta" is a giant, plastic-eating catamaran that collects trash on an industrial scale. and it's powered by renewable energy., julia zaltzman, julia zaltzman's most recent stories.

- This Boatmaker Builds 1960s-Inspired Cruisers With a Modern Twist. Here’s How.

- This 150-Foot Fishing Trawler Was Transformed Into a Rugged Explorer Yacht

- These 3 Miniature Explorer Yachts Are Ready to Take You Off-Grid

- Share This Article

Meet Manta , a giant, plastic-eating catamaran powered by renewable energy. The 185-foot hybrid sailboat will be the world’s first sea-cleaning vessel capable of collecting plastic waste on an industrial scale. Operating autonomously 75 percent of the time, it’s also a state-of-the-art scientific laboratory.

World-record sailor Yvan Bourgnon is the mastermind behind the venture. During 20 years of transatlantic competitions and various solo world tours (including the first person to sail solo from Alaska to Greenland), he witnessed a sharp increase in ocean pollution. In 2015, he was forced to abandon the Transat Jacques Vabre yacht race after his sailboat struck plastic debris in the Bay of Gascogne.

Related Stories

- Elon Musk Says the Tesla Roadster Will Use SpaceX Tech and Also Might Fly

This New 150-Foot Superyacht Can Cruise Through Shallow Waters in Florida and the Bahamas With Ease

- This New Camper Shell Lets You Sleep on the Roof of Your Rivian

Bourgnon’s response was to set up The SeaCleaners NGO in 2016, a consortium of over 58 engineers, technicians and researchers comprising five research laboratories and 17 external partners to build a solution: The Manta .

Manta has nets along the stern to collect plastic and garbage, along with sustainable energy sources like solar panels and wind turbines to power the onboard collection and recycling center. Courtesy SeaCleaners

“During my racing career, I’ve missed out on records and broken my boat 12 times from hitting ocean debris,” Bourgnon told Robb Report . “I’ve circumnavigated the world twice in my life, once at the age of 12 with my parents, and another 30 years later. The difference in the amount of plastic pollution was alarming. I knew something had to be done.”

Built from low-carbon steel, the Manta is a virtuous energy recovery unit wrapped up in a 185-foot sailboat design. It features a custom electric hybrid propulsion system enabling it to travel at controlled speeds of between two and three knots, the optimum speed for waste collection. Around 500kW of onboard renewable energy is generated via two wind turbines located at the stern, 500 square meters of photovoltaic solar panels at the bow, two hydro-generators under the boat and a Waste-to-Electricity Conversion Unit (WECU) used to power the hotel load, or what the captain and crew consume.

The Manta gets its name from a pair of retractable wings used to hold a third of the solar panels that mimic the shape of a manta ray. Despite being an oceangoing vessel, the Manta will primarily focus on coastal areas in and around the estuaries or mouths of the 10 most polluting rivers in the world. These include the Yangtze (the longest river in Asia), the Yellow River, which feeds into China’s Bohai Sea, and the Ganges, which runs through India and Bangladesh.

Two rear tenders Mobula 8 and Mobula 10 will clean up trash in shallower waters. Courtesy SeaCleaners

“Despite the boat’s capabilities, we’re not looking to operate in the middle of the oceans,” says Bourgnon. “Instead, we’ll be crossing the mouths of the rivers several times a day collecting the rubbish that continually spills into the sea. The 20 largest rivers in southeast Asia account for 60 percent of ocean plastic, so that’s where we’re concentrating our efforts.”

Three floatable collection systems give the Manta a plastic-eating span of 151 feet and a collection depth of three feet. Two cranes are used to extract large debris. Up to three tons of waste will be collected per hour and sorted on board by a crew of 22 working in two 12-hour shifts. Metal and glass are sent to shoreside recycling units, organic matter is returned to the sea, and plastic waste is fed into the WECU which vaporizes the plastic turning “syngas” into electricity. Operating for 300 days a year, the aim is to collect up to 10,000 tons per year. Two multi-purpose decontamination boats stored onboard— Mobula 8 and Mobula 10— will be deployed to access narrow and shallow areas. Both models will also be sold individually to encourage public and private initiatives.

The sailing cat plans to collect 10,000 tons of ocean trash each year. It will also be able to house marine biologists doing ocean research. Courtesy SeaCleaners

“We’ll be collecting dense areas of macro-plastic pollution before it sinks or disintegrates into micro-plastics,” says the Franco-Swiss navigator. “Hurricanes and tsunamis cause massive inflows of pollution into the ocean, and it’s imperative that this pollution is dealt with quickly before it drifts, sinks and becomes irrecoverable.”

A shipyard is yet to be confirmed, but Bourgnon anticipates a two year-build for the first model, with delivery scheduled for the end of 2024. Sea trials will take place in Europe before heading to southeast Asia in 2025 to begin the first clean-up. Up to 10 scientists are also accommodated on board. All the scientific research and data collected by the Manta will be made available on an open-source platform.

“I’m not in competition with other boat builders to be the only one with a Manta ,” says Bourgnon. “Our hope is that hundreds of Mantas will be built around the world to help with the great ocean cleanup.”

Read More On:

- Sailing Yacht

More Marine

Open Space, Eco-Friendly Tech: What a Rising Class of Millennial Superyacht Owners Is Looking For

‘People Don’t Want to Be Inside’: How the Outdoors Became Yachtmakers’ Most Coveted Design Element

This New 220-Foot Custom Superyacht Is Topped With an Epic Jacuzzi

Culinary Masters 2024

MAY 17 - 19 Join us for extraordinary meals from the nation’s brightest culinary minds.

Give the Gift of Luxury

Latest Galleries in Marine

Palm Beach Vitruvius in Photos

The 10 Most-Exciting Yacht Debuts at the Palm Beach International Boat Show

More from our brands, kering shares fall 11.9%, but broader luxury fears don’t surface, drake tightropes between athletic success, academic reform, m. emmet walsh, ‘blade runner’ and ‘blood simple’ actor, dies at 88, armory show director nicole berry to depart fair for role at the hammer museum, this folding treadmill is 20% off for amazon’s big spring sale.

- Search forums

- Sailing Anarchy

Mantra 28 and 31

- Thread starter plattlens

- Start date Feb 7, 2006

More options

- Feb 7, 2006

Design by Andrzej Arminski and build in Poland - any opinions?

- Feb 11, 2006

- Thread starter

plattlens said: Design by Andrzej Arminski and build in Poland - any opinions? Click to expand...

Kevlar Edge

Super anarchist.

check with me monday, i'm sure i will have info in the archives

Betty's Boy

Is this the one with identical rig dimensions to a Mumm 30? I think I read somewhere the idea was to be able to buy used OD sails and be a kind of training boat for would-be Mumm programs. Looks very nice in those pictures. Hvor seiler du, plattlens? BB

Betty said: Is this the one with identical rig dimensions to a Mumm 30? I think I read somewhere the idea was to be able to buy used OD sails and be a kind of training boat for would-be Mumm programs. Looks very nice in those pictures. Hvor seiler du, plattlens? BB Click to expand...

Latest posts

- Latest: Bump-n-Grind

- 2 minutes ago

- Latest: Bristol-Cruiser

- 4 minutes ago

- Latest: Ishmael

- 5 minutes ago

Sailing Anarchy Podcast with Scot Tempesta

- New Sailboats

- Sailboats 21-30ft

- Sailboats 31-35ft

- Sailboats 36-40ft

- Sailboats Over 40ft

- Sailboats Under 21feet

- used_sailboats

- Apps and Computer Programs

- Communications

- Fishfinders

- Handheld Electronics

- Plotters MFDS Rradar

- Wind, Speed & Depth Instruments

- Anchoring Mooring

- Running Rigging

- Sails Canvas

- Standing Rigging

- Diesel Engines

- Off Grid Energy

- Cleaning Waxing

- DIY Projects

- Repair, Tools & Materials

- Spare Parts

- Tools & Gadgets

- Cabin Comfort

- Ventilation

- Footwear Apparel

- Foul Weather Gear

- Mailport & PS Advisor

- Inside Practical Sailor Blog

- Activate My Web Access

- Reset Password

- Pay My Bill

- Customer Service

- Free Newsletter

- Give a Gift

How to Sell Your Boat

Cal 2-46: A Venerable Lapworth Design Brought Up to Date

Rhumb Lines: Show Highlights from Annapolis

Open Transom Pros and Cons

Leaping Into Lithium

The Importance of Sea State in Weather Planning

Do-it-yourself Electrical System Survey and Inspection

Install a Standalone Sounder Without Drilling

When Should We Retire Dyneema Stays and Running Rigging?

Rethinking MOB Prevention

Top-notch Wind Indicators

The Everlasting Multihull Trampoline

How Dangerous is Your Shore Power?

DIY survey of boat solar and wind turbine systems

What’s Involved in Setting Up a Lithium Battery System?

The Scraper-only Approach to Bottom Paint Removal

Can You Recoat Dyneema?

Gonytia Hot Knife Proves its Mettle

Where Winches Dare to Go

The Day Sailor’s First-Aid Kit

Choosing and Securing Seat Cushions

Cockpit Drains on Race Boats

Rhumb Lines: Livin’ the Wharf Rat Life

Re-sealing the Seams on Waterproof Fabrics

Safer Sailing: Add Leg Loops to Your Harness

Waxing and Polishing Your Boat

Reducing Engine Room Noise

Tricks and Tips to Forming Do-it-yourself Rigging Terminals

Marine Toilet Maintenance Tips

Learning to Live with Plastic Boat Bits

- Sailboat Reviews

Affordable Cruising Sailboats

Practical sailor reviews nine used boats over 35 feet and under $75,000..

In a search for a budget cruiser, Practical Sailor examined a field of used sailboats costing less than $75K and built between 1978 and 1984. We narrowed the field to boats with sufficient accommodations for four people and a draft of less than 6 feet. One way to approach a used-boat search is to look for sailboats with informed, active owners associations and high resale values. Practical Sailor’s quest for recession-proof cruisers led us to the Allied Princess 36, Bristol 35.5C, Endeavour 37, S2 11.0, Freedom 36, ODay 37, Niagara 35, C&C Landfall 38, and the Tartan 37. The report takes a more in-depth look at the Tartan, C&C Landfall, and Niagara.

Let’s say you’re looking to buy a boat for summer cruising along the coastal U.S. or on the Great Lakes, one that, when the time is right, is also capable of taking you safely and efficiently to Baja or the Bahamas, and perhaps even island-hopping from Miami to the West Indies. Like most of us, your budget is limited, so a new boat is out of the question. Let’s set more specifics:

- Passes a thorough survey by a respected surveyor and has been upgraded to meet current equipment and safety standards. (These are old boats, after all, prone to all sorts of potentially serious problems.)

- Fun to sail inshore (which means not too heavy and not too big).

- Sufficient accommodations and stowage to cruise four people for two weeks.

- Popular model (active owners support group for help and camaraderie) with decent resale value

- Under $75,000.

- Monohull (multihulls violate the price cap, anyway).

- Draft of less than 6 feet (for the islands, mon).

In the February 2008 issue, we examined 30-footers from the 1970s , which is just above the minimum length for the Big Three: standing headroom, enclosed head, and inboard engine. Too small, however, to satisfy our new criteria. So we need to jump up in size. As we culled through the possibilities, we found a fairly narrow range of boat lengths and vintages that satisfy the criteria. Of course, there always are exceptions, but basically it is this: 35- to 38-footers built between 1978 and 1984. Bigger or newer boats that meet our criteria cost more than $75,000.

Heres the list of nine models we came up with: Allied Princess 36, Bristol 35.5C, C&C Landfall 38, Endeavour 37, Freedom 36, Niagara 35, ODay 37, S2 11.0, and the Tartan 37. All were built by reputable companies in the U.S. or Canada, with underwater configurations ranging from full keels with attached rudders to fin keels and spade rudders. Displacements are mostly moderate.

Below we present notes on six of the finalists. Details of our 3 favorites are linked to the right of this page.

ALLIED PRINCESS 36

Allied Yachts developed an excellent line of cruising sailboats in the 1960s, including the first fiberglass boat to circumnavigate, the Seawind 30 ketch, which later was expanded to the 32-foot Seawind II. The handsome Luders 33 was the boat in which teenager Robin Lee Graham completed his historic circumnavigation. Arthur Edmunds designed the full-keel Princess 36 aft-cockpit ketch and the larger Mistress 39 center-cockpit ketch. None of these boats are fancily finished, but the fiberglass work is solid and well executed. They’re ocean-worthy, and affordable. The Princess 36 was in production from roughly 1972 to 1982. Wed look for a later model year; prices are under $50,000.

BRISTOL 35.5C

Bristol Yachts was founded by Clint Pearson, after he left Pearson Yachts in 1964. His early boats were Ford and Chevy quality, good but plainly finished, like the Allieds. Over the years this changed, so that by the late 1970s and early 1980s, his boats were between Buicks and Cadillacs in overall quality. This includes the Ted Hood-designed 35.5C. Its a centerboarder with a draft from 3 feet, 9 inches board up to 9 feet, 6 inches board down; a keel version also was available (named without the “C”).The solid fiberglass hull was laid up in two halves and then joined on centerline. It had an inward-turning flange on the hull, superior to the more common shoebox hull-to-deck joint. The 35.5C is very good in light air, but tender in a breeze. Pick one up for around $60,000.

ENDEAVOUR 37

The Endeavour Yacht Corp. was founded in 1974, and its first model was a 32-footer, built in molds given to it by Ted Irwin. Yup, the Endeavour 32 has the same hull as the Irwin 32. Its second model was the Endeavour 37, based on a smaller, little known Lee Creekmore hull that was cut in half and extended. Its not the prettiest boat in the world, and not very fast, but heavily built. Owners report no structural problems with the single-skin laminate hull. It has a long, shoal-draft keel and spade rudder. What helped popularize the Endeavour 37 was the choice of layouts: an aft cabin with a quarter berth, a V-berth and quarterberth, and a (rare) two aft-cabin model. Production ended after 1983. Prices are around $50,000.

After the Halsey Herreshoff-designed Freedom 40 that reintroduced the idea of unstayed spars, several other designers were commissioned to develop the model line-up. These included David Pedrick and Gary Mull; the latter drew the Freedom 36, in production from about 1986 to 1989. While the early and larger Freedoms were ketch rigged, models like the 36 were sloops, which were less costly to build and easier to handle. To improve upwind performance, a vestigial, self-tacking jib was added. Thats the main appeal of these boats: tacking is as easy as turning the wheel. The 36s hull is balsa-cored, as is the deck. Balsa adds tremendous stiffness, and reduces weight, which improves performance. The downside: Core rot near the partners on this boat could lead to a dismasting and costly hull damage. Interior finishing is above average. These boats sell right at our price break: low to mid-$70s.

This low-profile family sloop was second only to the ODay 40 in size of boats built by ODay under its various owners. Founded by Olympic gold-medalist George ODay to build one-designs and family daysailers, subsequent ownership expanded into trailer sailers and small- to medium-size coastal cruisers. Like the others, the 37 was designed by C. Raymond Hunt Associates. The center-cockpit is a bit unusual but some prefer it. The cruising fin keel and skeg-mounted rudder are well suited to shallow-water cruising, and the generous beam provides good form stability. The hull is solid fiberglass, and the deck is cored with balsa. Owners report it is well balanced and forgiving. Early 1980s models are on the market for less than $40,000.

Built in Holland, Mich., the S2 sailboat line emerged in 1973 when owner Leon Slikkers sold his powerboat company, Slickcraft, to AMF and had to sign a no-compete agreement. The 11.0 was the largest model, introduced in 1977. The designer was Arthur Edmunds, who also drew the Allied Princess 36, though the two are very different. Edmunds resisted some of the bumps and bulges indicative of the International Offshore Rule (IOR), but still gave the 11.0 fine ends, and a large foretriangle. Two accommodation plans were offered: an aft cockpit with conventional layout of V-berth, saloon, and quarter berth and galley flanking the companionway; and an unusual center-cockpit layout with V-berth forward immediately followed by opposing settees, and then galley and head more or less under the cockpit. The master suite is in the aft cabin, of course. The hull is solid fiberglass and includes the molded keel cavity for internal ballast; the deck is balsa-cored. Overall construction quality is rated above average. Prices range from about $30,000 to $50,000.

NIAGARA 35: a handsome cruiser with Hinterhoeller quality.

Austria-born George Hinterhoeller emigrated to Canada in the 1950s and began doing what he did all his life: build boats, first out of wood, then fiberglass composites. He was one of four partners who formed C&C Yachts in 1969. He left in 1975 to again form his own company, Hinterhoeller Yachts. The company built two distinct model lines: the better known Nonsuch line of cruising boats with unstayed catboat rigs, and the Niagara line. About 300 Niagara 35s were built between 1978 and 1995.

Canadian naval architect Mark Ellis designed the Niagara 35 as well as all of the Nonsuch models. He gave the 35 a beautiful, classic sheer with generous freeboard in the bow, swooping aft to a low point roughly at the forward end of the cockpit, and then rising slightly to the stern. The classic influence also is seen in the relatively long overhangs; todays trend is to lengthen the waterline as much as possible, with near plumb bows, discounting the old belief that overhangs were necessary for reserve buoyancy. So the Niagara 35 has a somewhat shorter waterline than the others in our group of nine, but as the hull heels, the overhangs immerse and sailing length increases. The short waterline also accounts for the 35s moderately high displacement/length ratio of 329. There is a direct correlation between the D/L and volume in the hull, and for a cruising boat, there must be sufficient space for tanks and provisions. Unfortunately, tankage in the 35 isn’t that much: 80 gallons water, 30 gallons diesel fuel, and 25 gallons holding tank.

The cruising fin keel is long enough for the boat to dry out on its own bottom should the need arise, like drying out against a seawall in Bali to paint the bottom. (Sorry-just dreaming!) The spade rudder seems a little unusual for a cruiser. When asked about it, Ellis said that it provides superior control to a skeg-mounted rudder, and that skegs, which are supposed to protect the rudder, often aren’t built strong enough to do the job. Circumnavigator and designer/builder/developer Steve Dashew agrees that offshore, in nasty conditions, spade rudders are the way to go.

Construction

George Hinterhoeller and his associates at C&C Yachts were early advocates of balsa-cored hull construction, because it reduces weight, increases panel stiffness, and lowers costs. The worry, of course, is delamination of the core to the inner and outer skins should water penetrate through to the core. This is why quality builders remove balsa coring wherever through-hulls or bolts pass through the hull or deck, and fill the area with a mix of resin and reinforcements. Hinterhoeller was such a builder, but core integrity still deserves close inspection during a pre-purchase survey.

All bulkheads are tabbed to the hull and deck with strips of fiberglass, and this is an important detail for an offshore boat. Many mass-produced boats have molded fiberglass headliners that prevent tabbing bulkheads to the deck; rather, the bulkheads simply fit into molded channels in the headliner, which do not prevent them from moving slightly as the boat flexes in waves.

Hardware quality is good. One owner described the chocks and cleats on his Niagara as “massive.” Hatches are Atkins & Hoyle cast aluminum, which are about as good as you can buy. And the original rigging was Navtec rod. Owners report no structural problems.

Performance

With its moderately heavy displacement, conservative sailplan, and relatively large keel, the Niagara 35 is not a speed demon, and does not point as high as a boat with a deep, narrow fin keel. But thats not what were after here. The 35s specs are just about what we want for a versatile cruising boat. Owners say performance picks up quickly as the breeze fills in. If the sailplan were larger, for improved light-air performance, youd have to reef sooner, and reefing is work.

The long keel has another advantage, and that is improved directional stability over shorter keels, which means less effort at the helm. We tend to think that a powerful below-deck autopilot can steer any boat, but autopilots struggle, too. A boat thats easy for the crew to hand steer also is easy for the autopilot to maintain course.

A lot of Niagara 35s were equipped with Volvo saildrives rather than conventional inboard diesel engines. Advantages of the saildrive: improved handling in reverse and lower cost. Disadvantages: potential corrosion of aluminum housing and not as much power. Various inboard diesels were fitted: Westerbeke 27-, 33-, and 40-horsepower models, and a Universal M35D, all with V-drives. Owners rate access somewhat difficult.

Accommodations

Two interior layouts were offered: the Classic, in which the forepeak has a workbench, shelves, seat, and stowage instead of the usual V-berth; and the Encore, which has an offset double berth forward, and quarter berth and U-shaped galley aft. The saloon in the Classic, with settees and dining table, is farther forward than usual; the head and owners stateroom, with single and double berths, is aft. Both plans have their fans.

Headroom is 6 feet, 4 inches in the main cabin and 6 feet, 2 inches in the aft cabin. Berths are 6 feet, 7 inches long; a few owners say berth widths are a bit tight. A couple of thoughts on the double berths offered in these two plans: V-berths are subject to a lot of motion underway and so do not make great sea berths, but at anchor, ventilation via the forward hatch makes them far more comfortable than a stuffy aft cabin, where its much more difficult to introduce air flow. Offset double berths do not waste outboard space like V-berths do, but the person sleeping outboard must crawl over his/her partner to get out of bed.

Thirty-year-old boats should be surveyed thoroughly. Nothing lasts forever, but boats well maintained last a lot longer. Pay particular attention to the balsa-cored hull and deck. If either has large areas of delamination, give the boat a pass, because the cost to repair could exceed the value of the boat.

A few owners expressed concern about the boats handling off the wind, which surprises us somewhat. A test sail in lively conditions should answer that question.

We much prefer the inboard. If you prefer the saildrive, look for signs of corrosion and get a repair estimate.

Niagara 35 Conclusion

The Niagara 35 is a handsome, classically proportioned cruising sloop from one of the best builders of production boats in North America. It is not considered big enough these days to be a circumnavigator, but certainly large enough for a couple to leisurely cruise the Bahamas, Caribbean Sea, and South Pacific. We found asking prices ranging from around $54,000 to $89,000, with most in the $60,000 range.

C&C LANDFALL 38

As noted, George Hinterhoeller was one of four partners who formed C&C Yachts in 1969, at Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario. The others were Belleville Marine, Bruckmann Manufacturing, and the design firm of George Cuthbertson and George Cassian. From the beginning, the emphasis was on performance. Indeed, the 40-foot Red Jacket won the 1968 Southern Ocean Racing Circuit (SORC).

In 1973, Cuthbertson retired to his Ontario farm, citing burn-out. Eight months later, he was back as president of C&C Yachts, telling staff that they ought to pursue more multi-purpose racer/cruiser models. C&C became the dominant boatbuilder in North America, with models ranging from the C&C 24 to the C&C 46, with models just about every 2 feet in between. The Landfall cruiser series was introduced in 1977, with the Landfall 42. It was followed by the Landfall 35, 38, and 48. Production of the 38 ran from 1977 to 1985, with about 180 built.

The C&C Landfall 38 is directly related to the earlier C&C 38. We wrote in our original 1983 review that the older hull design was “…modified with slightly fuller sections forward, a slightly raked transom rather than an IOR reversed transom, a longer, shoaler keel, and a longer deckhouse for increased interior volume.” The spade rudder is not everyones first choice on a serious cruising boat, but it does provide superior control. And the Landfalls have a higher degree of finish inside, along with layouts more suited to family cruising.

The Landfalls perform very well, thanks to lightweight construction and speedy hull forms. The Landfall 38s displacement/length ratio of 272 is the lowest of the three compared in this review.

Notable drawbacks: a V-berth that becomes quite narrow forward, and as noted in the 1983 review, “a hull that rises so quickly aft that C&Cs normal gas bottle stowage at the end of the cockpit is eliminated.” This on a cruising boat no less, where a hot meal is often the highlight.

Like nearly all the C&C designs, the Landfall 38 is attractively proportioned with sleek lines and a modern look, even several decades later. It appears most dated in the raked bow, but this better suits the anchoring duties on a cruising boat anyway.

Materials and building processes used in C&C Yachts are very similar to those of the Niagara 35, namely because of Hinterhoeller. Practices he established at C&C continued after he left, at least for the short-term. So what we said about the Niagara 35s balsa-core construction also applies to the Landfall 38, where it is found in the hull, deck, and cabintop.

The hull-deck joint is through-bolted on 6-inch centers, through the teak toerail, which gaves the Landfall series a more traditional look than the distinctive L-shaped anodized aluminum toerail Cuthbertson designed and employed on the rest of the C&C models. The joint is bedded with a butyl tape, which does a good job of keeping out water, but doesn’t have the adhesive properties of, say, 3M 5200. On the other hand, if you ever had to remove the deck-heaven forbid!-it would be a lot easier.

Deck hardware is through-bolted with backing plates or large washers, although some of the fasteners come through on the underside, where the core transitions into the core-less flange. We also saw this on our old 1975 C&C 33 test boat. It means two things: water migrating down the fastener after the bedding fails can contact a little bit of balsa, and uneven stresses are placed on the fastener, which above deck can cause gelcoat cracks.

Proper bronze seacocks protect the through-hulls, and hoses are double-clamped for added security. The mast butt is not deep in the bilge where it can corrode in bilge water, but rests on two floor timbers in the sump, above any water that would typically collect.

The external lead-ballast keel is bolted through the keel sump in the hull. Its run is flat, and the boat can sit on its keel, allowing it be careened against a seawall for bottom painting, prop repairs, or other work in locales where boatyards are rare.

In our earlier review, we noted that the engine compartment has no sound insulation, despite its proximity to the owners berth, but gluing in some lead-lined foam is within the capability of most owners.

Despite being 2,000 pounds heavier than the C&C 38, the Landfall 38 is still a quick boat. Its old PHRF rating of 120 is just a little higher than the Cal 39 at 114, and less than the Tartan 37 we’ll look at next.

The mast is a little shorter than that of the C&C 38, but as with most boats of the IOR era, the Landfall 38 has a large foretriangle of 385 square feet. A 150-percent genoa measures 580 square feet, which is a handful for older crew. Roller furling with maybe a 135 percent genoa would be a logical way to minimize the effort required to tack this boat.

Strangely, the Landfall 38 did not come standard with self-tailing winches; a highly recommended upgrade. The main halyard, Cunningham, and reefing lines are led aft to the cockpit, while the headsail halyards run to winches on deck near the mast.

The boat is stiff and well balanced. Owners like the way it handles and appreciate its speed.

The standard engine was a 30-hp Yanmar diesel. The early Yanmar Q series had a reputation for being noisy and vibrating a lot. At some point, C&C began installing the Yanmar 3HM which replaced the 3QM. Power is adequate. The standard prop was a solid two-blade. Engine access leaves a lot to be desired.

The interior is pushed well into the ends of the boat to achieve a legitimate three-cabin accommodation plan. The standard layout was a V-berth forward with cedar-lined hanging locker. The berth narrows quickly forward so that tall people might not find enough foot room. Moving aft, there is a dinette and settees in the saloon, U-shaped galley and large head with shower amidships, and a double berth in the port quarter, opposite a navigation station. In rainy or wild weather, youll want to close the companionway hatch and keep weather boards in place so that water doesn’t spill into the nav station. Installing Plexiglas screens on either side of the ladder will help.

Oddly, there is no place to install fixed-mount instruments outboard of the nav table; that space is given to a hanging locker, but could be modified. Other than this, about the only other shortcoming is that the toilet is positioned so far under the side deck that persons of average size cannot sit upright. And, the head door is louvered, which compromises privacy.

There is not a lot to complain about with the Landfall 38 that we havent already said: the V-berth forward is tight, theres no sitting upright on the toilet, theres no place to install electronics at the nav station, and the nav station and aft berth invite a good soaking through the companionway.

Construction is above average, but have a surveyor sound the hull and decks for signs that the fiberglass skins have delaminated from the balsa core. Small areas can be repaired, but our advice is not to buy a boat with widespread delamination.

Landfall 38 Conclusion

The Landfall 38 is an excellent family boat and coastal cruiser. Its popularity in the Great Lakes region is not surprising. Island hopping to the Caribbean is also within reach, but any longer cruises will likely require more tank capacity and stowage. Standard tankage is 104 gallons water and 32 gallons of fuel. Prices range from around $55,000 to $65,000.

TARTAN 37: shoal draft and S&S styling.

In the early years of fiberglass boat construction, the major builders-Columbia, Cal, Morgan, Tartan, and others-commissioned well-known naval architects to design their models. Today, this work is more often done by a no-name in-house team over which the company has more control. Tartan Yachts of Grand River, Ohio, relied almost exclusively on the prestigious New York firm of Sparkman & Stephens; they’d drawn the Tartan 27 for the company’s antecedent, Douglass & McLeod, and were called on again to design the Tartan 37, which had a very successful production run from 1976 to 1988.

The Tartan 37 has the modern, clean, strong lines that typified S&S designs. The bow is raked, and the angle of the reverse transom is in line with the backstay-an easily missed detail that nevertheless affects the viewers impression of the boat. Freeboard is moderate and the sheer is gentle. In an early review, we wrote: “Underwater, the boat has a fairly long, low-aspect ratio fin keel, and a high-aspect ratio rudder faired into the hull with a substantial skeg.” In addition to the deep fin keel, a keel/centerboard also was offered. A distinctive feature is how the cockpit coamings fair into the cabin trunk. Its displacement/length ratio of 299 and sail area/displacement ratio of 16.1 rank it in the middle of the 9-model group (see table, page 9), so while it looks racy, its not going to smoke the other nine.

From its beginning, Tartan Yachts set out to build boats of above average quality, and this can be seen in both the finish and fiberglass work. Some unidirectional rovings were incorporated in the hull laminate to better carry loads; like the vast majority of boats of this era, the resin was polyester. Vinylester skin coats, which better prevent osmotic blistering, had yet to appear. Some printthrough is noticeable, more on dark-color hulls. The hull and deck are cored with end-grain balsa, which brings with it our usual warnings about possible delamination. The hull-deck joint is bolted through the toerail and bedded in butyl and polysulfide. Taping of bulkheads to the hull is neatly executed with no raw fiberglass edges visible anywhere in the interior. Seacocks have proper bronze ball valves. One owner advises checking the complex stainless-steel chainplate/tie rod assembly, especially if its a saltwater boat.

Shortcomings: Pulpit fasteners lack backing plates. Scuppers and bilge pump outlets have no shutoffs.

Under sail, the Tartan 37 balances and tracks well. As noted earlier, its not a fireburner, but not a slug either. Its no longer widely raced, but the few participating in PHRF races around the country have handicaps ranging from 135-177 seconds per mile. The Niagara 35 now rates 150-165, and the C&C 38 126-138.

The deep fin-keel version points a little higher than the keel/centerboard because it has more lift, however, the deep draft of 6 feet, 7 inches is a liability for coastal cruising.

Because of the large foretriangle and relatively small mainsail, tacking a genoa requires larger winches and more muscle than if the relative areas of the two were reversed. For relaxed sailing, jiffy reefing of the main and a roller-furling headsail take the pain out of sail handling.

The 41-horsepower Westerbeke 50 diesel provides ample power. Standard prop was a 16-inch two blade. A folding or feathering propeller reduces drag, thereby improving speed. Access to the front of the engine, behind the companionway ladder, is good. Unfortunately, the oil dipstick is aft, requiring one to climb into the starboard cockpit locker-after you’ve removed all the gear stowed there.

The layout below is straightforward with few innovations: large V-berth forward with hanging locker and drawers; head with sink and shower; saloon with drop-down table, settee, and pilot berth; U-shaped galley to starboard; and to port, a quarterberth that can be set up as a double. To work at the navigation station one sits on the end of the quarterberth. This plan will sleep more crew than most owners will want on board, but its nice to have the option. Pilot berths make good sea berths but often fill with gear that can’t easily be stowed elsewhere.

The fold-down table, like most of its ilk, is flimsy. Underway, tables should be strong enough to grab and hold on to without fear of damaging it or falling-thats not the case here. And the cabin sole is easily marred trying to get the pins in the legs to fit into holes in the sole.

Finish work in teak is excellent, though this traditional choice of wood makes for a somewhat dark interior. Today, builders have worked up the nerve to select lighter species such as ash and maple.

Eight opening portlights, four ventilators, and three hatches provide very good ventilation.

The standard stove was alcohol, which few people want anymore, owing to low BTU content (which means it takes longer to boil water), the difficulty in lighting, and almost invisible flame. Propane is a better choice, but there is no built-in stowage on deck for the tank, which must be in a locker sealed off from the interior and vented overboard. (You could mount the tank exposed on deck, but that would not complement the boats handsome lines.)

Theres not much to pick at here, but we’ll try. Centerboards come with their own peculiar set of problems: slapping in the trunk while at anchor, broken pendants and pivot pins, and fouling in the trunk that inhibits operation.

Often what sets apart higher-quality boats from the rest of the fleet is the cost of materials and labor in making up the wood interior. They look better than bare fiberglass, work better because they have more drawers and stowage options, and are warmer and quieter. The unnoticed flip side is that the joinerwork tends to hide problems, like the source of a leak. When all the fasteners are neatly bunged and varnished, it takes courage to start pulling apart the interior!

Checking engine oil is unnecessarily difficult, and to operate emergency steering gear (a tiller) the lazarette hatch must be held open, which could be dangerous. Lastly, the companionway sill is low for offshore sailing; stronger drop boards would help compensate.

Tartan 37 Conclusion

The enthusiasm for this boat is strong. In fact, theres a whole book written about it, put together with the help of the Tartan 37 Sailing Association (link below). You’ll pay in the mid- to high-$60s, which ranks it with the Niagara 35 and Freedom 36 as the most expensive of our nine. While Tartan 37s have made impressive voyages, and are as capable as the Niagara 35 and C&C Landfall 38, like them, its not really a blue-water design. We view it rather as a smart coastal cruiser and club racer. Good design and above-average construction give it extra long life on the used-boat market.

Classic Cruisers For Less Than $75,000

Niagara 35 Sailnet Forum

C&C Photo Album

Tartan Owners

Tartan 37 Sailing Association

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

27 comments.

Great article, but why did you leave out your namesake build – Camper Nicholsons Nicholson 35. Very similar to the Niagara 35, except that it trades the (less than useful – my opinion) quarter berths for two GIGANTIC cockpit lockers. And I find the transverse head on the Nic a civilized alternative to telephone booth head/shower combinations.

While the Nic claims 6 berths, you’ll never find that many on ours. Cocktails for 6, dinner for 4, sleeps 2 is our mantra

This is great information and a good guideline to go by. Thanks for the heads up on theses vessels.

Every time Practical Sailor does a review of boats in the 35- to 38-footers built between 1978 and 1984, they always leave out the Perry designed Islander Freeport 36 and 38. Many people are still cruising in these great boats, and among Islander Yachts designs this one is a wonderful cruiser.

I was also sad to see that. We sail a ’79 I-36, and it is stiff, fast, forgiving, and a very comfortable cruising platform. While many of the 800+ built are ready for the wrecking ball, there are some excellent, well cared for boats available. They are lovely sailors.

Couldn’t agree more, with Islander Freeport 36 & 38 raised coachroof that opens up all sort of possibilities and transom based swim ladder, her utility is unmatched.

These are all nice boats. I have sailed most of them. I owned a Tartan 37 for 4 yrs. As A US Sailing Cruising instructor, I have sailed and cruised hundreds of boat. This is one of the best balanced and behaved boats that I have sailed. She will sail on jib alone with no lee helm and sail main alone with minimal weather helm. Few boats will do this. She tracks quite well in a seaway. There are only 2 instances that you need to put the centerboard down: clawing off a lee shore or racing upwind. Otherwise she is just fine with board up. I have not had problems with the board slapping in a rolley anchorage. I keep the board up tight all the way and no problem. And my boat a 1983 had a built in propane vented locker. Also my dipstick was forward port and easy to reach, but not so for the filter so I remote mounted it forward. S & S did a great job on this design. And a 4 foot draft is wonderful and special feature for a boat that sails so well.

Surprising that the author did not address the obvious question, “if you had to pick one of these for a bluewater cruise, which one would it be?”

I too would appreciate the author’s response to this question.

Every time I star liking one of these I see the word ‘balsa’

Why did you not look at the Catalina 36. They are sea kindly; easy to repair and get parts; there’s a lot of them; and newer ones are in the price range you are talking about.i.e. my 2002, well fitted, is $72500.

Good article, thanks.

Pearson 365 conspicuously missing from this list.

Excellent article with factors that almost all of us who own vintage older cruising sailboats have considered at one time or another. However, when making my choice and before putting my money down, I also included PHRF as a factor. Without degenerating into a large discussion of pros and cons of PHRF (or any other indexes of performance), I think that you should consider performance in the equation. While livability is important (and I am a comfort creature), the ability to run away from a storm or handle tough conditions, is also important, you don even mention it. Paraphrasing Bill Lee, “faster is fun”. After weighing all of the factors discussed above, and adding considerations for performance, I purchased a 1984 Doug Peterson designed Islander 40 for $65,000 and am still in love with the boat 15 yrs later. It still is a “better boat than I am a sailor” and is also very comfortable. The only drawback is that it draws 7’6″ which in SF Bay, is not a problem. On the “right coast” that might be a problem, but on the “correct coast” it has not been.

Hate to be picky but you left out of this old list a high quality design and blue water capable cruiser designed and made by quality Canadian company–Canadian Sailcraft, namely CS 36 T. A Sailboat 36.5 feet with all the necessary design and sailing numbers needed to be attractive , safe, and fast.

No one likes to see their favorite boat left off a list like this, but it must be done. But my Ericson 38 has almost none of the cons of the boats in this article, and most of the desireable pros. After 13 years of ownership, it hasn’t even hinted at breaking my heart. Great design pedigree, glassed hull/deck joint, ahead of its time structural grid, points high, extremely liveable interior, and the list goes on…so much so that I’m glad I didn’t buy ANY of the boats in the article instead.

Missing are the CSY 37 and 44. Ernest M Kraus sv Magic Kingdom CSY 44 walkover cutter

Very useful article. Thanks! I’d love to see the same framework for a selection of length 40′-50’ft coastal cruisers.

I know that it is hard to include all boats, but you missed a boat that fills all the requirements. I’m speaking about the Bob Perry designed and Mirage built 35. It has all the capabilities and handling characteristics that you would want in a capable cruiser and the speed of a steady over-performing racer-cruiser. It has 6’5″ headroom and all the standard features that are a must in a strong well built beauty with 5 foot draft, light but rigid and strong. Great for the Chesapeake bay or other depth challenging bodies of water.

Great publication through the year’s. Still miss my print version to read on rainy day. Owned a Cal 27 T-2 and Irwin Citation over the years. Sailed on the Chesapeake. The Irwin ended up in Canada. JA

We have a Swallow Craft Swift 33. The boat was made in Pusan Korea in 1980. For a 33′ boat it is cavernous. We live aboard 1/2 the year. I thought it might be a boat you would be interested in looking at. I call it a mini super cruiser.

How about the Pearson 367?

Surely this is a joke. I’ll put the Nonsuch 30 Ultra against anyone.

Good article, but another vote for the CS36T. No better value for an offshore capable, fast cruiser and built to last.

Great article

The list looks familiar to the list I was working with back around 2004. Back then the prices were even higher of course. To fit my budget, I got a great boat… Freedom 32. That is a Hoyt design from TCI. All I really gave up was some waterline. Below deck, the boat is as roomy as many 35-36 footers due to the beam. I find it to be a great boat for me. I do not see a move up to the sizes on this list to improve my lot. I could be tempted by a Freedom sloop over 44′ but that is retirement noise.

which edition of month/year of the PS Magazine is this covered in please, it would be great to know?

A great article, but what about the Young Sun 35 Cutter! a great offshore boat that I have sailed single handed from Canada to Hawaii and back, single handed, in rough conditions, but which was an incredible 30 days each way. Overall 40 ft. and 11 ft. beam. I believe also built by Bob Perry!

LEAVE A REPLY Cancel reply

Log in to leave a comment

Latest Videos

Island Packet 370: What You Should Know | Boat Review

How To Make Starlink Better On Your Boat | Interview

Catalina 380: What You Should Know | Boat Review

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- Online Account Activation

- Privacy Manager

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Newsletters

- Sailboat Reviews

- Boating Safety

- Sailing Totem

- Charter Resources

- Destinations

- Galley Recipes

- Living Aboard

- Sails and Rigging

- Maintenance

- Best Marine Electronics & Technology

- By Quentin Warren

- Updated: August 5, 2002

Among the more comfortable new cruising catamarans to make 1996 debuts, the impressive Manta 40 consolidates roomy accommodations, refined deck systems and first-rate construction.

At 40 feet, the hulls are long and sleek enough to counteract visually the freeboard required for volume below. The fine, plumb bows, cutting a strikingly delicate wake, are spanned by a composite beam that supports port and starboard foredeck trampolines and ties structurally into the decks. The bridge deck’s rounded pod is fit with wraparound portlights forward. Our test boat was equipped with a “Radar Arch/Hardtop/Dinghy Davit Pac,” featuring a welded, anodized-aluminum Bimini structure and davits for a sizable tender. The superstructure is substantial, but suits the boat’s cruising agenda.

Construction is fastidious, benefiting from the experience of Manta’s Pat Reischmann who has been involved in state-of-the-art composite technology since it first began to change the face of boatbuilding. All elements of the boat are vacuum bagged. Hull, deck and bulkheads utilize a varying schedule of traxial, biaxial and unidirectional cloth applied with isophthalic and vinylester resins. Below the waterline, the hulls feature solid glass and vinylester; above the waterline and in the deck, Nida-Core polyproylene honeycomb reduces weight and increases stiffness and strength. Where deck fittings occur, aluminum backing plates are inserted into the actual layup. The hulls-to-deck detail includes 3M 5200 adhesive sealant, mechanical fasteners on 10-inch centers and glass tabbing.

Access to twin 30-horsepower Volvos with Sail Drives is excellent. Plumbing lines, thru-hulls, filters, strainers, wiring, tankage and the like are impeccably organized and easily serviced and are fit with first-rate hardware. Two house battery banks totaling 360 amp-hours and a pair of dedicated 75-AH start batteries complement a 110-volt shore-power system that includes a 50-amp converter for battery charging. The Manta’s “Comfort Pac,” from extra batteries and high-output alternators to a generator and an electric head, can take power options into the realm of luxury.

The light and cheerful interior, with a lot of easily maintained vinyl and acrylic, is accented with varnished teak trim and highly durable synthetic teak-and-holly soles. On the bridge deck, a brilliant U-shaped galley to port serves the dinette, across from which a serious navigation station sits. The hulls are reserved for sleeping and ablutions, the port hull for the owner’s double cabin aft and private head with shower forward.

Sail control lines in the cockpit are nicely choreograhed. A very roachy, full-batten main with controls at the helm and a self-tacking Camber Spar jib that virtually takes care of itself on the bow provide good but easily managed power. The boat is solid enough and stable enough to relish a blow; our light-air test at least gave us the opportunity to confirm that the 40 is a responsive performer in a wide range of conditions.

This newest Manta pleasingly blends sophisticated technology and beautiful construction with the features to fulfill the needs and desires of a typical cruising couple.

Manta Enterprises Inc. 7855 126th Avenue North Largo, FL Phone:(813) 536-8446

Manta 40 Specifications:

- LOA: 39’8″ (12.1 m.)

- LWL: 39’0″ (11.9 m.)

- Beam (max): 21’0″ (6.4 m.); 53% LOA

- Draft: 3’8″ (1.12 m.)

- Disp: 13,000 lbs. (5,897 kgs.)

- Sail area: 798 sq.ft. (74.2 sq.m.)

- Mast above water: 59’6″ (18.2 m.)

- Length/Beam (hulls): 9.5:1

- Underwing clearance: 2′; 5% LOA

- Cabin Headroom: 6’4″ (1.93 m.)

- Disp/Length: 97.8

- SA/Disp: 23.1; Bruce #: 1.2

- Fuel: 100 gal. (378 ltr.)

- Water: 100 gal. (378 ltr.)

- Holding: 30 gal. (114 ltr.)

- Auxiliary: 2 x 30-hp Volvo diesel

- Designer: Manta Enterprises

- Base price: $204,950

- More: 2001 - 2010 , 31 - 40 ft , catamaran , Coastal Cruising , manta catamarans , multihull , Sailboat Reviews , Sailboats

- More Sailboats

Balance 442 “Lasai” Set to Debut

Sailboat Review: Tartan 455

Meet the Bali 5.8

Celebrating a Classic

Kirsten Neuschäfer Receives CCA Blue Water Medal

2024 Regata del Sol al Sol Registration Closing Soon

US Sailing Honors Bob Johnstone

Bitter End Expands Watersports Program

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Email Newsletters

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

TAKING ACTION

Concrete solutions against pollution

Reducing marine plastic pollution through innovative technology. This is MANTA INNOVATION’s mission, The SeaCleaners integrated engineering bureau, with the support of a pool of industrial and academic partners.

Rising up to the challenge

Under the banner of MANTA INNOVATION, the technical team develops a range of groundbreaking solutions against plastic pollution among which a bold and original project: the Manta . This first-of-a-kind processing ship is designed to collect, treat and repurpose large volumes of floating plastic debris present in highly polluted waters, along the coasts, in estuaries and in the mouths of large rivers.

In 2022, Bureau Veritas, the leading ship classification company, awarded the Manta with “Approval In Principle” certification. The Manta is now fit to be built.

Explore the Manta

The Manta, a giant of the seas against pollution

Collection systems.

Objective of 5 to 10,000 tonnes per year.

The Manta extracts both floating macro-waste and smaller debris from 10 millimetres upwards and up to one metre deep.

Depending on the density and closeness of the layers of waste, the Manta can collect between 1 to 3 tonnes of waste per hour, with the objective of collecting 5 to 10,000 tonnes per year. It can operate for up to 20 hours a day, 7 days a week.

The Manta is equipped with four complementary collection systems:

- Waste-collecting conveyors, which bring the waste on board. - Three floatable collection systems, which have a collection span of 66 metres, and pick up surface waste. - Two small, multi-purpose collection boats, or “Mobulas,” which can pick up both micro- and macro-plastic waste from the shallowest and narrowest parts of the ocean that the Manta can’t get to. - Two lateral cranes, which pull out the largest pieces of floating debris from the water.

Waste Recycling

90% of waste processed at sea.

The Manta is the first self-sufficient workboat capable of processing 90 to 95% of the collected plastic waste whilst at sea. This is all thanks an innovative, eco-friendly system, which consists of:

- A waste sorting unit: this manually separates the waste, according to its type, and packages it in a way that boosts its energy efficiency. - A waste-to-energy conversion unit: this converts the collected waste into electricity which, in turn, powers all of the Manta’s electrical equipment. This eco-friendly method emits hardly any CO2 or pollutants into the air.

Nothing is discarded during this process. All the collected waste is converted into useful components, in line with the principles of a circular economy.

Storage Capacities

200 m3 of storage for of all types of waste.

The Manta’s primary purpose is converting waste into energy, as opposed to storing it, as this increases the ship’s weight and energy consumption.

The waste that isn’t immediately repurposed is packaged into big bags and stored on the deck or the hulls, before it is eventually converted into energy.

The storage capacity for the plastic waste is 140 m3 (around 50 tonnes). In addition to this, there are two 33 m3 containers: one for drift nets and one for dangerous waste.

In rare cases where the waste isn’t converted into energy, it is entrusted to local waste treatment or recycling plants during stopovers.

Eco-conception

100% eco-conscious.

We have carried out a complete Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of the Manta: we assessed the environmental impact associated with all the stages of the boat's life cycle. This includes everything from the first stage of the Manta’s assembly (the extraction of necessary resources), all the way to the last stage of its life cycle. The LCA enabled us to determine the highest quality, most eco-friendly, and most recyclable materials, as well as those with the lowest carbon footprint.

As a result, the hulls of the Manta will be made of 95% recyclable steel and the superstructure, with a cabin and wheelhouse, will be made of 100% recyclable aluminium.

This assessment also made it possible to find the right balance between the boat’s materials and its weight, ensuring that the Manta is as energy-efficient as possible.

Autonomy of action

Target: 50 to 75% energy autonomy.

The Manta can operate without using fossil fuels between 50% to 75% of the time, making it the first workboat to have such a high level of energy self-sufficiency. In order to minimise its energy consumption and carbon footprint, the sails and riggings are its preferred means of propulsion.

Due to its high energy independence, the boat also has an almost unlimited range, which allows it to rapidly reach intervention zones all over the world. These are typically mouths and estuaries of great rivers where the layers of waste are concentrated, or areas hit by climate hazards and/or natural disasters.

Its embedded clean shipping technologies make the Manta a model of "green ship" and "smart ship".

Green energy

500 kW of clean energy.

The Manta has several pieces of on-board equipment designed to generate renewable energy, which enables it to minimise its environmental footprint and consumption of fossil fuels, and simultaneously increase its energy self-sufficiency:

Two wind turbines (100kW)

Almost 500m² of photovoltaic solar panels (100 kWp)

Two hydrogenerators (100 kW) by means of a propeller driven by the sail-powered forward movement of the boat

The waste-to-energy conversion unit (100 kW)

To comply with regulatory requirements, the Manta has 2 diesel motors on-board in order to facilitate low-speed manoeuvres and to guarantee the safety of the crew.

Hybrid propulsion

Top speed of 12+ knots.

The Manta is fitted with a hybrid propulsion system, combining automated rigging from the DynaRig model, and propeller propulsion units driven by electric motors.

The electricity needed to power the rigging and electric motors is supplied by the on-board equipment designed to generate renewable energy, the waste-to-energy conversion unit and conventional generators.

Sailing is the Manta’s preferred mode of transport. The hybrid propulsion system allows manoeuvring at low speed for sensitive operations (such as the entry to and exit from ports), as well as waste collections, which are carried out at 2 or 3 knots, all whilst maintaining a reduced ecological footprint.

Agile and energy-efficient, the Manta can reach a top speed of over 12 knots.

Scientific laboratories

10 scientists on-board.

The Manta is a place of work for institutional research teams from all over the world, with the purpose of advancing the knowledge of the scientific community in the fields of geolocation, quantification and the characterisation of plastic waste.

6 to 10 scientists at a time can come aboard the Manta for on-board assignments. Whilst at sea, they’ll have oceanographic equipment and four research spaces at their disposal: two research labs, a study room and an analysis room.

The data collected will be completely accessible via Open data.

Educational platform

60 m² conference space for up to 80 people.

Also hailed as an ambassador boat for the protection and decontamination of oceans, the Manta is open to the public during on-land stopovers to foster individual and collective action in support of marine conservation.

The 60 m² conference room on-board the Manta can accommodate up to 80 people, providing a space to raise awareness about marine conservation amongst the general public.

The Manta also serves as a platform that presents a tangible example of effective technological solutions that, in turn, aid in the development of circular economy systems at a local level. Economic stakeholders and local authorities will have the opportunity to visit the Manta and discover its waste repurposing unit, the Mobulas, its collection systems, its scientific labs, etc.

Batteries Electric motors of the propulsion units Waste water treatment Freshwater production Technical premises Rudders Propellers (submerged)

Dimensions of the Manta: Height: 62 m Width: 26 m (66 m with outriggers) Length: 56.5 m Weight: 1,800 tons

Rafts for MOBULAs 8 and 10 Storage area for navigational waste Food storage area and cold storage Sports hall Technical premises Generating sets

Collectors Wind turbines Sorting and preparation plant for collected waste Waste-to-energy conversion unit Conference room Analysis office and scientific laboratories Hydro-generators (submerged) Waste storage area Storage containers for hazardous waste and large waste (drift nets) Gantries for outriggers and haling floatable collections systems Infirmary Technical premises

Wheelhouse Gantries for side outriggers and floatable collections systems Outdoor waste storage area Rescue boat Diving boat Cranes Cabins Kitchen Cafeteria & Mess

Automated rigging Fixed solar panels Retractable wings equipped with solar panels Sundeck

Acting where the need is

Launch of the manta in 2025.

- Finalisation of the technical feasibility study

- Demonstrator testing of collection systems

- Preliminary design studies

- Detailed design studies

- System selection

- Shipyard research phase

- Launch of the MOBULA 8

- 1st shipyard consultations

- Integration studies and systems testing

- Equipment selection

- 1st MOBULA 8 campaigns

- Circulation of consultation specifications

- Request for Interest (RFI) to shipyards

- Approval in Principle with Bureau Veritas

- Request for Proposals (RFP) to shipyards

- Launch of the Detailed Design and Procurement

- Commissioning of MOBULA 10

- Selection of a shipyard

- Start of construction of MANTA

- Systems' integration

- Separate commissioning of systems

- Integrated commissioning of systems

- Completion of MANTA construction

- Launching of MANTA

Our latest articles

25 January 2024

Why should plastic waste be collected at sea?

2024 action plan: milestones and challenges for The SeaCleaners

17 July 2023

Successful new sea trials for Manta’s surface collection systems for floating waste

19 June 2023

Manta, Mobula, awareness… How was the Z Event money used?

15 February 2023

There is no such thing as a small gesture!

17 January 2023

1st successful sea tour for MANTA’s surface waste collection systems

18 July 2022

“Approval in Principle” of the plastic-hunter ship The Manta: the giant of the seas fit for construction

14 June 2022

The MANTA ready to level up

12 April 2022

Expanding our horizon

14 March 2022

How much progress on the Manta Project?

The Manta Boat : from an utopia to a giant of the seas

The Manta Boat

New steps in the design of the giant of the seas

Technical Consortium

The result of 3 years of Research and Development, the Manta mobilized a technical consortium of 17 industrial partners and 5 research laboratories for its design, including world leaders in their field. Since 2018, 60 engineers, technicians and researchers have worked more than 45,000 hours to bring the Manta’s vision to fruition. Each of the ship’s “technological bricks” is the result of a synergy of unique know-how. In 2022, Bureau Veritas, a leader in ship classification, awarded the Manta “Approval In Principle” certification. The Manta is now fit to be built.

Waste-to-energy unit

Automated rigs, energy management and optimisation, manta (naval & plant architecture), collection boats (mobulas), production of renewable energy, eco-design (ecoplex project), belt collection systems, collection systems by nets, detection and guidance systems, certification (approval in principle), why remove floating marine waste.

Because action speaks louder than words

The Manta is designed to collect floating marine debris in zones where it collects in large volumes, before it disperses and permanently enters the marine ecosystem. A virtuous circle will ensue: by restoring the ecosystems and local economies damaged by plastic pollution it will demonstrate fast, visible results which will in turn increase awareness, mobilise public authorities, private companies, communities and individuals.

Because the capabilities exist and need to be shared

The Manta will be an ambassador vessel, showcasing innovative, efficient, viable and easily replicated technologies to collect and repurpose plastic waste. The capabilities on board will be made available to local stakeholders so that they can in turn contribute to the circular economy in their own country.

Because several activities can be located in one place

The Manta will be a pioneering scientific platform for observation and research into plastic pollution, as well as a learning centre to raise awareness among the general public and communities directly affected by the problem.

To know more : read the article Why do we need to collect plastic waste ?

Become a sponsor

Join the Manta project by becoming a sponsor

The collectors are located between the vessel’s two hulls. They bring waste aboard quickly so that it can be treated in the on-board plant. The collectors operate during the day, “sucking up” the waste while the vessel continues to be maneuvered.

Floatable Collection Systems

Waste floating on the surface is collected using floatable collection devices: two nets are attached to each side of the Manta via outriggers, and a central net is attached to the stern. Floatable collection systems are preferably used at night in coastal areas where there is less marine traffic and surface trawling is permitted.

The collection nets are hung on the outriggers. When deployed, the outriggers give the Manta a collection span of 66m.

Two side cranes, located on the main deck, extract larger floating debris (such as drifting fishing nets or debris from ashore) from the water. Specially trained divers also help with this operation. This debris is then stored on board and brought back to shore to be processed via the appropriate channels.

The Manta carries aboard Mobula 8, a multi-service, multi-purpose 8m collection boat that can be used in calm and/or protected waters such as rivers, slow-moving waters, ports, lakes, areas with stilt housing and mangroves.

Mobula 10 is a multi-service, multi-purpose 10m collection boat that can be used in rivers with strong currents and in coastal waters less than 5 nautical miles off the coast. Both Mobula are carried aboard inside the Manta’s hulls, but can also be deployed autonomously for localized clean-up projects.

Sorting unit

After collection the waste is sent to a sorting unit where it is transported to sorting tables manned by three operators. The operators are responsible for manually separating plastic waste from other types of waste such as metals, organic materials, glass, aluminum or containers that could contain toxic, hazardous or unknown products. Plastic waste is then conditioned to increase its energy efficiency, i.e., dried, ground and homogenized, prior to being repurposed.

To avoid any harm to marine life, organic waste, such as wood, algae and living organisms, is immediately returned to the water through a hatch on the sorting plant floor.

Solid residue

The heat generated during the process is captured for use by the Manta. The solid residue (char), which represents about 10% of the processed plastic, is stored to be repurposed ashore in the form of asphalt, cement, fuel, etc. Thanks to the processing and filtration system, this process emits very little CO 2 and very few polluting emissions into the air, in compliance with European regulatory standards.

Waste that is not immediately repurposed is packaged in large waste bags and stored, to be converted into energy at a later date as needed – either during the same mission, to sail from one patch of waste to another, or during a future mission.

Large waste storage

Two 20-foot waste storage containers are located on Deck 3. They are used to store both hazardous and large waste such as drifting fishing nets.

Storage capacity

Storage capacity for plastic waste on-board the Manta has been optimized, representing approximately 206 cu.m (140 cu.m + two 33 cu.m containers), i.e., more than 50 tonnes.

Energy self-sufficiency

The Manta features a number of innovative technologies designed to maximize its energy self-sufficiency and limit its overall carbon footprint. The materials used to build the boat were also carefully chosen to limit its environmental footprint.

Life Cycle Assessment

Conducting a Life Cycle Assessment helped us rise to the challenge of making the Manta a technological marvel, perfectly adapted to its missions, while making the most environmentally friendly choices in the short, medium and long term.

Environmental impact

Everything aboard the Manta has been designed to minimize the boat’s environmental impact. Take, for example, its hybrid propulsion system, which relies mainly on sail power, its various renewable energy production equipment (wind turbines, solar panels, hydro‑generators), its waste-to-energy conversion unit and its propulsion units powered by electric motors.

Sails and riggings

In order to minimize the boat’s energy consumption, carbon footprint and operating costs, whenever possible the Manta uses its sails and riggings to get around, enabling it to run autonomously 50% to 75% of the time, without using fossil fuels.

The Manta’s large energy production and storage capacity, as well as its hybrid propulsion system (sail and engine), give it maximum autonomy for its cruising and operating phases.

The Manta is an ocean-going vessel capable of covering 3,500 nautical miles (6,500 km), the equivalent of a transatlantic crossing, without having to sail along the coast or make stopovers.

Wind turbines

Two wind turbines located on Deck 3 on the boat’s stern produce 100 kW of electricity.

Solar panels

Nearly 500 sq.m of photovoltaic solar panels are installed on the bow. About two‑thirds of their surface area are fixed in place, with the rest on retractable wings. These wings are what gave the boat its name – when they are extended, the boat looks like a manta ray. The solar panels produce about 100 kWp of electricity.

Hydro-generators

Two hydro-generators located under the boat produce 100 kW of electricity. The hydro-generators work using a propeller that is powered by the boat’s movement through the water when sailing.

The waste-to-energy conversion unit adds 100 kW to the energy mix. Through this unique combination of marine-based renewable energy sources, the Manta is powered by wind, sun, sea… and plastic.

Sails are the Manta’s preferred mode of travel. The riggings are improved Dynarig models that have been specially developed to reduce energy costs and the ecological footprint of sailboats.

Hybrid propulsion combines automated rigging, which supports the sails, and propeller propulsion units powered by electric motors. These conventional generators are used for sensitive maneuvers, such as entering and exiting ports, and low-speed operations, such as waste collection.

Energy management

A customized on-board energy management system determines the most efficient combination of energy sources from among those available on board to meet the consumption needs of current missions. The unique system includes a routing module that looks at the weather forecast and determines the most efficient routes in terms of energy production and hybrid propulsion (engine and/or sails).

The Manta will sail at an average of 6 knots and have a top speed of more than 12 knots using either the sails only or both the sails and the engine. In collection mode, the vessel travels at just 2 to 3 knots, to avoid harming marine life.

Scientific missions are carried out on board in order to geo-position, quantify and record details of waste patches during collection campaigns. At their disposal are work rooms, a dry lab, a wet lab, and oceanographic equipment.

The scientific missions also facilitate interdisciplinary discussions and accelerate the implementation of preventive and corrective measures. Research results will be published and data collected will be available in an “open data” platform. The aim is to advance the fight against plastic pollution backed by scientific results.