- F1 Australian Grand Prix

Sydney to Hobart 1998 tragedy, 20 years on: Sword of Orion skipper Rob Kothe speaks

Rob Kothe could not have known it at the time, but safety was so close. Another hour of ploughing south on Bass Strait through the hellish storm of the 1998 Sydney to Hobart, and conditions would have eased off.

But having measured winds of 90 knots (167km/h), Kothe decided that it was time to retire from the race and pointed his boat - Sword of Orion, a Reichel-Pugh 44 - towards Melbourne. He thought it was the best chance of safe passage out of the chaotic low-pressure system, the worst the famous race had ever seen.

Kothe broke the race rules of the time by informing other boats of the extreme winds via radio, prompting 30-40 vessels to retire and seek port in Eden on the NSW South Coast.

“I thought, ‘People are going to die if they go into this’,” Kothe told Wide World of Sports . “I was disinterested in the result.”

Kothe and his crew had been well-placed in the race and therefore, were well past the safe haven of Eden. Charting north-west in an attempt to clear the storm, they were actually headed into more trouble; the extreme weather system was wrapping around the Victorian coast, and Sword sailed that way with mountainous waves to her back and side.

Sailors were given an ominous weather forecast before the race, though not to the catastrophic proportions that eventuated. Forecasts were Sydney-centric, Kothe said, rather than drawing far more accurate information from Victoria and Bass Strait readings. And there was precious little information during the race, per the rules. Boats could not relay weather observations, only their position.

“We were flying blind,” said Kothe, who was contesting just his second Hobart and had only owned the Sword since May.

At the yacht’s helm as it turned back was Glyn Charles, a 33-year-old British sailor who finished 11 th in the Star class at Atlanta 1996. He was a well-liked guy whom Kothe had met only a month before, as Charles prepared in Sydney for the 2000 Olympics.

A sailor who preferred smaller boats and reportedly did not much like ocean racing, Charles was one of two men on deck when the Sword was pounded by a 40-foot wave. It dropped down the face and completed a full 360-degree roll, like a tumbling barrel. Steering was lost.

After the boat snap-rolled, it was left to the sailor who had been spotting for Charles, Darren Senogles, to scream: ‘Man overboard!’

It is believed that Charles was hit by the boom, suffering serious injuries. The coroner later concluded that his safety harness also failed. He was in the water, without a life jacket and weighed down by wet weather gear and boots. He would never leave.

Kothe had been at the navigation station and was thrown upside down in the air. He took out the companionway steps with his head and injured his leg, landing beneath sails and other debris as 18 inches of water filled the boat. He needed other crew members to help free him, before they realised something was terribly wrong on deck.

“It was chaos, but everyone focused on the man overboard,” Kothe said.

“Darren Senogles went to put a rope around himself to dive in the water [to swim after Charles]. But the waves were so high and the wind was so strong that we were just blown away. Within 10 seconds, we were too far apart to reach him.”

All they could do was watch helplessly Charles drift away until he was out of sight. His body was never recovered. Kothe thinks of him often.

“I do. You think, ‘What could I have done differently?’” Kothe said.

“Obviously I shouldn’t have turned back but with the information I had, it seemed like the best decision. It totally wasn’t.”

There was no time to reflect on that call at the time, or to grieve for Charles. The motor was gone. The mast was wrapped around the boat; the tip up the side, the base inside, threatening to skewer the stricken vessel.

“As soon as Glyn had disappeared from sight, the focus turned to cutting away the rig to stop the boat being hole-punched and us all drowning,” Kothe said.

“People were in shock. They realised Glyn was gone. But there were many times through the night where we thought we were all gone.”

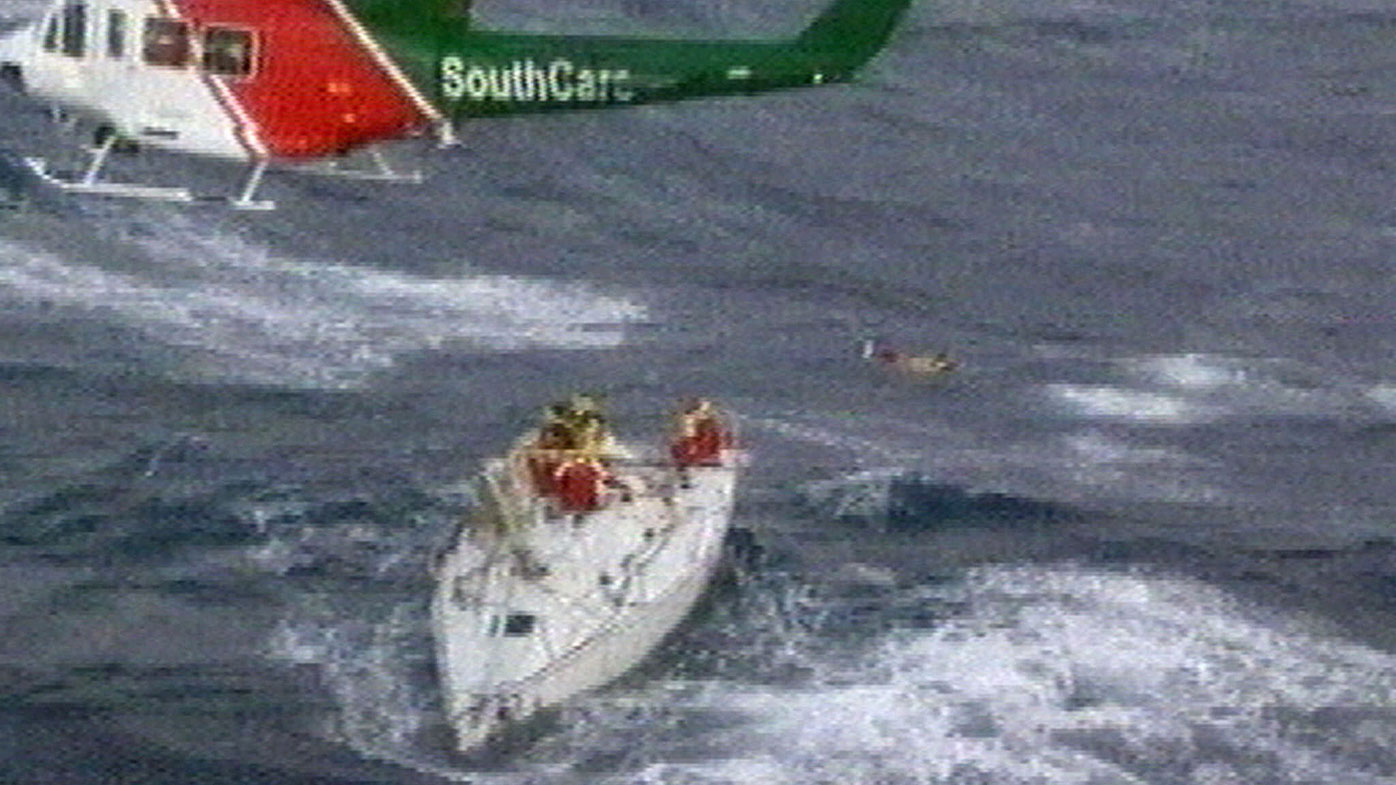

In those conditions, even getting rescued was extremely dangerous. A Navy Sea King helicopter reportedly spent two hours searching for the Sword before it was located.

Two sailors were rescued before a third – Steve Kulmar, a veteran on his 17 th Hobart – entered the water. Wearing a heavy kapok ‘Mae West’-style life jacket, Kulmar twice fell out of the harness connected to the helicopter winch and spent an exhausting half-hour in the water until he was found by a frogman, dispatched because the chopper was running low on fuel.

Kulmar’s crew mates thought he was dead, meeting the same fate as Charles.

“People were having awful trouble getting up to the helicopters,” Kothe said.

“Steve Kulmar was out of contact with our boat and the helicopter for three or four minutes. We thought he was gone. They actually did put a swimmer in the water, and that’s the only way they got him.”

The rest of the crew had to wait until first light, about 6am, for their ticket out. Conditions remained horrendous.

“I was standing in the belly of the boat trying to figure out why the helicopter was going up and down, and up and down. Of course, it was holding stationary – we were going up and down,” Kothe said.

The chopper spotlight gave Kothe a look at his boat. It had been ruined by the storm.

“The boat was just slowly twisting and tearing,” Kothe said.

“When we left the area, I had my eye on the boat and lost sight of it after about 15 seconds, because it was white and so were all the wave tops.

“The following day, they sent out a fishing boat to try and find it. It was never found. It just tore apart.”

Marc Pavillard was the navy chopper pilot who saved the remainder of the crew. One moment is burned in his mind.

“I’ll never ever forget the faces of the Sword crew as we abruptly broke clear of the storm on the way home,’’ he told the Daily Telegraph .

“It was as if this thick curtain had just been opened into the most magnificent blue sky day you have ever seen.

“I was shocked by it. They couldn’t believe what they were seeing. I got it because they had been in hell for a couple of days and just on the other side, within their reach, was this realisation of paradise.’’

That the Sword’s crew was rescued after remaining in the relative safety of their boat was a blessing. Three crew members of another yacht – John Dean, James Lawler and Michael Bannister, of Winston Churchill – drowned after leaving their vessel on a life raft.

Two other sailors – Bruce Raymond Guy and Phillip Charles Skeggs, of Business Post Naiad – died of a heart attack and drowning, respectively.

Six sailors died. Fifty-five had to be rescued. Five boats sank and seven were abandoned. Just 44 of 115 yachts finished the race.

The comfort that Kothe takes from the heartbreaking race is the dramatic changes that happened immediately afterwards, and have happened ever since.

A leading sailing journalist, Kothe just wrote his recollection of the ’98 race for Yachts and Yachting , outlining the extensive changes made after coronial recommendations and at the sport’s own initiative.

Key among them is the vastly different attitude towards sharing weather information.

“There’s been enormous changes. There were immediate changes for the ’99 Hobart,” said Kothe, who sailed a new Sword of Orion the following year.

“The most obvious one was that they changed the rule from the situation where there was no outside help on information about weather, to a compulsory situation (of weather information sharing).

“The whole scene grew up. People realised that lives were at stake in this thing and it was time to not be kids. That continued for quite a while.

“They didn’t die in vain. Because it forced a total rethink.

“I think about it a lot but I’m just cheered by the lessons learned. They haven’t just applied to people in that race, they’ve applied to people in other races, and cruising people. The advances in safety have helped fishermen, cruising sailors, commercial sailors … everybody. The lessons learned from that race have saved many lives.

“That’s the thing that I said to Glyn’s family, and say to everybody: they didn’t die in vain.”

Bill Sykes, who raced on Kendall Airways in ’98 and will contest his 30 th Hobart this year, said the loss of Charles weighed heavily on his fellow sailors.

“That was so sad. Such a young person. He was just a young kid,” he told Wide World of Sports .

“Most of us have come from smaller boats and we work up into the bigger boat. He was doing the same things we’ve all done and it just so happened that this wasn’t his race. It’s so sad. Such a nice kid.”

But the veteran sailor agreed that the safety advancements in sailing after the ’98 race had been remarkable.

“The sport’s much safer now than it ever has been,” Sykes said. “It changed every culture for racing.”

Kendall Airways was a 36-footer, the smallest boat Sykes has ever raced the Hobart on; certainly smaller than famed yacht Brindabella, on which he’d taken line honours the previous year. A mate with whom Sykes did his first-ever Hobart, Gary Eiszelle, talked him into making the voyage on the timber vessel.

Yet unlike the ill-fated Sword, Kendall Airways cleared the most dangerous weather and actually turned around to assist with search and rescue.

Sykes said the conditions were extreme.

“It was a shock to go through something like that,” he said.

“There are things you don’t remember, and then you remember what’s gone on in the race days later. We sailed through a pod of pilot whales, about 30 or 40. We nearly hit them, we were right in the middle of them. I didn’t remember that until I got back a couple of days later. It was just traumatic.

“When you’re involved in a traumatic event … you just don’t know what’s going on. It’s the middle of the night and there’s 40-foot waves coming at you, you could hear the roll of the little waves. There’s no wind down the bottom but there’s so much wind at the top. You do that for 24 hours, longer than that I think.

“That night-time stuff … you think about a lot of things.”

The thing that stuck in Sykes’ mind, amid everything else, was a freakish piece of poise and skill from Kendall Airways owner Jeff Cordell. A CSIRO technician, Cordell found that the yacht’s radio had come to grief and somehow managed to fix it as the storm raged around him.

“I’ve seen some people do some pretty smart things but in the middle of the race ... he soldered the radio back together again. And we helped with some of the coordination in the search and rescues,” Sykes said.

“This was in a boat pounding through in the middle of the night, headlight torches, soldering a radio back together. Pitch black, 40-50-foot waves smashing the boat and here he is soldering a radio back together. And here it is booming straight back out after that. Unbelievable. That’s probably the most vivid thing in my memory.”

The Kendall Airways crew had a simple mantra to stick to.

“It was a Tasmanian boat – it had to go home. That was the saying on the boat,” Sykes recalled.

In Hobart, the race’s tight-knit community was in deep shock. A memorial service was held. Apart from racing against Charles, Sykes knew Bannister from around the Manly area. Those lost sailors will never be forgotten and the pain of their loss remains 20 years on.

Their legacy to the race is that no more sailors need die as they did.

- sydney to hobart yacht race

More Sports News

Yachting World

- Digital Edition

1998 Sydney Hobart: Extract from The Proving Ground by G Bruce Knecht

- Tom Cunliffe

- April 20, 2020

Helpless crew can do nothing except watch as one of their own, swept overboard during a capsize, drifts away in a storm

Red flare and liferaft deployed – crew of the stricken yacht Stand Aside wait for rescue by helicopter in the 1998 Sydney Hobart Race. All photos: Richard Bennett

G Bruce Knecht, sometime foreign correspondent of The Wall Street Journal , has risen nobly to this challenge in his book The Proving Ground . Originally published in 2001 in the aftermath of the tragedy, the book is now available via Amazon – and it should be required reading for all who go offshore to compete.

Within a framework of the race in general, Knecht has concentrated mainly on the events surrounding four boats. Sword of Orion is ultimately abandoned in the direst distress, Winston Churchill is lost, but Sayonara and Brindabella finish.

From meticulous research and endless interviewing of those involved, Knecht has produced a book that is hard to put down. Not only does he describe the events accurately, he takes the bold step of looking critically into the characters and motivations of the dramatis personae.

The book is skilfully crafted by a master and not written as a linear time line, but this has made it difficult to find an extract of suitable length for publication in Yachting World . I have eventually centred on the loss of Glyn Charles, an Olympic sailor from Britain, one of the crew of Sword . Charles joined the crew late in the day as a ‘rock star’ helmsman.

What went wrong and why, as described below, brings us right on board the yacht and it makes for harrowing reading.

From The Proving Ground by G Bruce Knecht

At about 1600, the owner Kooky’s requirement for giving up the race was surpassed as the wind reached close to 70 knots. By then, the yacht was 90 miles from the safe haven of Eden. In racing terms, Sword of Orion was still doing well, but even so he told his shipmate Kulmar he was prepared to give up. ‘It’s up to the helmsmen. If they want to go back, we’ll go back.’

Kulmar already knew what Brownie and Glyn would say, but he quickly checked with both of them before telling Kooky it was unanimous. ‘Fine, let’s do it,’ Kooky said.

‘But where are we going to go?’ Dags the permanent hand interjected. ‘We can’t head directly to Eden. That would put the waves behind us.’

Article continues below…

The inside story of the nail-bitingly close 2019 Sydney-Hobart race

Had any of the crew of the nine yachts that finished the inaugural Sydney Hobart Yacht Race in 1945 been…

Fastnet Race 1979: Life and death decision – Matthew Sheahan’s story

At 0830 Tuesday 14 August 1979, aged 17, five minutes changed my life. Five minutes that, despite the stress of…

Hunched over a map, Kooky suggested that they head west, roughly in the direction of Melbourne, until it was safe to turn toward Eden. At 1644 Kooky announced Sword ’s retirement over the radio, Brownie got out of his bunk and told Kooky, ‘I’ll take the helm when we turn around.’ Kooky said no. ‘Glyn’s on the wheel; he can do it.’

Glyn already had a plan. ‘I’ll wait for a big wave,’ he said. ‘As soon as we’re over the top, I’ll turn the wheel hard as we go down the other side. There’ll be less wind between the waves, and we should be able to get around pretty fast.’

Being on deck was painful. The wind was ripping through the rigging, producing a constant high-pitched shriek. And having created the waves, the wind had gone into battle with them, shaving off the foam at their peaks and creating a jet stream of moisture that looked like smoke. The droplets slapped Glyn and Dags with skin-stinging speed.

All the waves were huge, but after letting several pass Glyn judged one to be larger than the others. ‘This is the one,’ he shouted. The angle increased dramatically as Sword climbed the 35ft wave. Just before it reached the top, Glyn pulled at the wheel, hand over hand.

As Sword passed over the crest and began to tilt forward, the rudder came out of the water. When it resubmerged a couple of seconds later, the Sword carved a tight arc as it skidded down the wave. By the time it reached the valley, it was on a new course.

‘Great job,’ Dags shouted, but he had already begun to worry about Glyn’s ability to drive the boat. Rather than steering the westerly course they had talked about, he was heading north.

‘How are you feeling?’ Dags asked. Glyn, who had a stomach bug and was prone to seasickness, admitted to feeling terrible and then went on to say how bad he felt about not putting in more time at the wheel. ‘I haven’t done my job. I’ve let the team down.’

‘No, that’s not true. Shit happens. If you’re not feeling well, it’s not your fault.’

AFR Midnight Rambler , skippered by Ed Psaltis, battles through the atrocious conditions

The waves were no larger than before Sword changed course, but now they were far more dangerous. The almost northerly course Glyn was steering would take them directly to Eden, but it meant the waves were coming astern. That meant Sword was doing exactly what Dags had desperately wanted to avoid – surfing, vastly increasing the chances of going out of control and rolling over.

Glyn wasn’t really looking at the waves. Having cinched the cord in his hood so tightly around his face that he looked as if he were wearing blinkers, he seemed to be paying more attention to the instruments.

Dags, not sure what to do, shouted over the wind, ‘Do you want me to steer?’ With his eyes focused on the compass, Glyn replied, ‘No, I can do it. It makes me feel better.’ Almost pleading, Dags said, ‘But you can’t steer this way. We have to go into the waves.’

Glyn was obviously miserable. His jacket was equipped with rubber seals around his neck and wrists, which were supposed to keep water out, but a steady stream was trickling down his back and chest, causing him to tremble with cold. ‘This gear is worthless,’ he said bitterly. ‘I’m completely wet. I wish we could just get out of here.’

‘You have to stop surfing,’ Dags insisted. ‘Why don’t you let someone else steer?’ Glyn said nothing.

Dags wasn’t the only crewman who was worried about Glyn’s steering. Clipping his harness onto the safety line, the experienced Carl Watson made his way to the back of the boat. ‘Glyn, your course is too low — you have to come up so we can keep heading into the waves.’

‘Don’t worry,’ Glyn replied without making eye contact. ‘I had friends who died in the Fastnet Race . I know what to do.’

- 1. From The Proving Ground by G Bruce Knecht

- 2. Below decks

- 3. Drowning

- 4. The right response?

- 5. Dry land

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Man overboard!

Glyn Charles didn't see the 40ft wall of water until it was too late. It had approached the Sword of Orion from behind, slightly from the port side, and seconds after the yacht began to ride up ward, the wave began to break. When the tumbling white water caught up to the boat, it turned the Sword sideways to the wave and made it impossible for Glyn, a 33-year-old British Olympic sailor, to steer. At the same time, the torrent of water tipped the Sword on to its side, and as it fell down the wave, the mast was parallel to the surface of the sea. After the hull crashed into the trough, the momentum forced the Sword to capsize.

Darren 'Dags' Senogles, the only person who was on deck with Glyn, was connected to the Sword by his safety tether, which was secured to the deck at one end and to a harness that was wrapped around his chest at the other. Although the tether saved him from being washed away from the yacht, it then pulled him underwater. Seconds later, the inverted hull, hit by another wave, began to twist, turning until it completed a 360 roll, still dragging Dags along by his tether. When the Sword returned to its upright position, he was floating in the water, still connected to the Sword. It was lurching from side to side, giving Dags, who was 28 and energised with adrenaline, a chance to grab at a stanchion and pull himself back on board. Once there, he saw that the mast had fallen. The rigging, a tangled mess made of metal, lines and wires, was wrapped around the port side of the boat like spaghetti. The top half of the aluminium steering wheel wasn't there anymore either. It looked like it had been sheared off.

Something else was missing.

Where was Glyn?

At first, Dags guessed he was in the water, connected to the yacht but unable to hoist himself on to the deck. Then he saw Glyn's orange tether. One end was still attached to the deck, but at the other there was only frayed nylon. Looking up, Dags saw a small figure in the water, 30ft away. Frozen but then bursting, Dags emptied his lungs.

'Man overboard!'

One day earlier, on Saturday, 26 December 1998, Rob Kothe's alarm clock had sounded at 3.30am. It was less than 12 hours before the start of the Sydney to Hobart Race, one of yachting's most challenging contests. The owner of the Sword of Orion began the day by filling a mug with his favourite drink, Sustagen, a vitamin-fortified chocolate mix, into which he sprinkled a teaspoon of ground coffee beans. Walking into his study, he logged on to his computer and called up data from the same global weather models that professional forecasters use. He spent the next three hours comparing the models, printing out charts and data, while straining the largest of the coffee particles from his drink through his teeth.

Rob was relatively new to sailing. He bought his first boat in 1997, the same year he raced his first Hobart - but he believed he could make up for his lack of experience with the same sort of relentless striving that had made him a successful entrepreneur. A tall and gangly 54-year-old, he didn't have much hair on the top of his head, although he did have a broad snow-white moustache and a goatee, which extended out over a long, almost pointy chin. The overall impression was that of a mad professor, and for that reason many members of the Cruising Yacht Club, which has sponsored the Sydney to Hobart Race since 1945, called him Kooky Owner, or simply KO. The young men he recruited for his crew called him Kooky.

Although Kooky was a tall man, he had been short as a youth, and that had left him with an abiding hunger for the kind of glory that winning the Hobart could bring. 'I was the smallest kid in school until I was nine. I felt bad about that,' he said more than 40 years later. 'It gave me a point to prove.'

In 1998, Kooky was deeply committed to winning the legendary race from Sydney to Hobart, which lies 630 miles south on the east coast of Tasmania.

A month before the Hobart, Kooky had met Glyn Charles, a boyishly handsome professional sailor with a mop of curly dark hair. Kooky loved the idea of adding an Olympic-quality helmsman to his crew. Glyn had been in Australia working as a sailing coach. Since he hoped to represent Britain in the Sydney Olympic Games, he was also spending time sailing small boats across the harbour to develop an intimate understanding of its wind patterns. He was ranked fourth in the world for the Star Class, a 22.5ft, two-man keelboat, and he had placed 10th in the Atlanta Olympics. Small boats were his passion. They were what attracted him to sailing, and, unlike many sailors who move to bigger boats as their skills expand, Glyn revelled in the total control he could have over a small one.

Glyn didn't like ocean racing, in part because he was prone to seasickness. But even though he had been planning to leave Australia on 22 December so he could spend Christmas in England with his family and girlfriend, he agreed to meet Kooky 10 days before the race. If he joined the Sword, he could add the Hobart to his sailing résumé - and also make some money. He asked for £1,000. At first, Kooky said he couldn't pay an outright fee because it wasn't permitted under the race rules. A little later, though, he said, 'I'm sure we can come to some arrangement.' He eventually offered to reimburse Glyn for various expenses, including his flight to England, and to pay about a £1,000 for some 'consulting work'. Glyn accepted.

Just after the race started at 1pm, forecasters at the Bureau of Meteorology examined the latest output from several forecasting computer models, which had just arrived. Two of the models predicted a centre of low pressure with much more intensity than had been anticipated.

If the models held true, the first part of the race would be a joyride. The wind, like the current, would come from the north, providing a substantial but manageable tail wind. But it looked like the intensifying storm would hit the fleet some time after most of the yachts began crossing Bass Strait, which separates the Australian mainland from Tasmania. With no land to block the wind or waves from the east or west, the strait is the worst possible place to run into bad weather.

The forecasters didn't know precisely how dangerous the vortex would be, but at 2.14pm on Saturday, more than an hour after the race had begun, the bureau issued a 'storm warning', and predicted wind of 40 to 55 knots.

Glyn was at the Sword of Orion's wheel when the warning was issued. The spinnaker was up, there wasn't a cloud in the sky and the boat was moving through the water at an average speed of 13 knots.

Kooky knew the Sword was doing well, although he didn't project any sense of excitement. He spent most of his time below, seated in front of the navigational instruments at the 'nav station', gathering weather information from faxes and commercial radio stations, and jotting down the wind speeds and barometric pressure reported from various on-land locations. He wasn't really alarmed by the prospect of 40 to 55 knot winds. That would be more than the average Hobart, he thought, but not by much. What did concern him, though, was the lack of precise information about the storm's trajectory.

When Adam Brown, a burly 29-year-old who everyone called Brownie, took the Sword of Orion's wheel at 8am on Sunday, a line of black cloud stretched all the way across the horizon in front of the yacht, like a wall delineating another realm. The shape of the sea was also changing. The waves were further apart from each other and much taller, some of them 30ft high. The overall pattern also was becoming more irregular, and every half an hour or so, a particularly large wave moved in a direction that was somewhat at odds with the others. As the great cloud got closer, it still looked like a single mass, although it had begun to reveal dark grey vertical ribs that extended down to the sea. 'It's going to be a helluva downpour when we go under that thing,' Brownie said to Dags, who was helping him to spot the waves and turn the wheel.

Everyone else was below. Not that the cabin was a comfortable sanctuary. Everything was wet, it was too loud to talk without raised voices, and the air reeked of vomit. Standing was difficult, both because of the turbulence and because it added to the feeling of nausea. Most of the crewmen were lying in bunks or on the floor of the cabin.

By late morning, the Sword's anemometer was indicating sustained wind speeds greater than 50 knots. Steve Kulmar, the Sword's most experienced crewman, was more nervous than he had ever been in a lifetime of ocean sailing, and he was beginning to wonder if they should abandon the race. 'In 17 Hobarts, I've never seen anything like this,' he told Kooky. 'In 1993, we had steady 40-knot wind and there were gusts of 75 and 80 - but the gusts were brief and there weren't these big waves.'

A little later, he added, 'We should think about going back.'

'We can't do anything until we know where the low is,' Kooky replied.

The very idea of quitting was repulsive to Kooky. Besides, leaving the race might be more dangerous that staying in it. The Sword was already south of Eden, the nearest port. At this point, turning toward it would have required the Sword to sail away from the waves, which would have been dangerous. On the other hand, finding shelter along Tasmania's eastern coast would require the Sword to cross Bass Strait. Without knowing where the storm was centred or where it was moving, Kooky thought it was impossible to evaluate the options.

For Steve, a successful advertising executive who had sailed his own yacht in Britain's Admiral's Cup regatta and who had never had much respect for Kooky, the idea that he was making the big decisions seemed absurd. Going on deck to have another first-hand look at the conditions, Steve said to Brownie: 'This isn't sailing. Don't you think we should be thinking about dropping out?'

'Absolutely,' said Brownie.

After the wind gusted to more than 70 knots, Steve confronted Kooky again. 'I'm very uncomfortable. I've never seen anything like this, and we don't have a choice: we need to retire.'

'We can't. We have to know more about what's going on with the weather.'

On deck, Brownie continued to get plenty of first-hand insight into the storm. When Dags, who had returned to the cockpit, spotted a 40-foot wave, he screamed. 'Bad wave - this one is huge!'

Brownie reminded himself of what he had to do: carve into the wave, maintaining enough speed to make it over the top, but not so much that the yacht charged off the peak. Not making it over the top would be the worst disaster, but he also had to avoid crashing into the trough on the other side with hull-cracking momentum. Brownie's execution was flawless, but he knew he had been wrestling with the waves far too long and that he wouldn't be able to handle many more like the previous one. Yet no one offered to relieve him. Cold and exhausted, he began pounding on the deck for attention. Even then, there was no reaction. Every minute was an ordeal. His arms were burning with pain, and he knew he was putting everyone at risk by continuing.

Finally, Steve appeared on the deck and took the wheel. Brownie had been steering for more than five hours. His muscles were trembling, as was his lower lip, which had turned blue. After he staggered below and sat at the foot of the stairs, Kooky thought he was suffering from hypothermia. Or worse. 'He's going into shock,' Kooky declared. 'For Christ's sake, give him something to drink.'

Thirty minutes after Steve took the wheel, Glyn got out of his bunk and told Kooky he wanted to drive. He had been badly seasick for several hours, but he knew there was a shortage of helmsmen. Since he, unlike the others, was being paid, he felt guilty about not doing more. He also hoped that being in fresh air and having something to do would help him feel better.

'How are you feeling?' Kooky asked.

'Well enough to take it on - and I won't be as sick if I'm on deck.'

'OK, but take another seasickness tablet.'

'I can't. They won't stay down, but I'll be fine.'

Glyn was clearly in bad shape. Just before he climbed up the stairs to the cockpit, he vomited on the shoulder of Simon Reffold, another crewman.

While Dags was opposed to the idea of turning around, he also was troubled by the degree of contrary thinking, particularly among the best helmsmen. All of them - Steve, Glyn and Brownie - wanted to quit. Even more to the point, Dags worried about who would steer the boat in conditions that required the most seasoned crew members. Brownie, the only one of the three who wasn't seasick, was a wreck. Dags thought Steve seemed reluctant to be on deck. And it was not at all clear that Glyn could do the job for long. Dags also recognised that there was an emotional component as well: although it may have been impossible to make a truly informed judgment on how to find calmer water or avoid going back into the storm, he knew most of the crew would be comforted by the idea, regardless of its merit, that they were heading toward land.

'Maybe we should go back,' he said to Kooky. 'We may end up going right back into the worst of it - but everyone's spirits are really down. Going back would give them a lift.'

'You may be right,' Kooky said. 'The last thing I want to do is quit, but it's hard to find logic in hell. This isn't racing any more - and it's getting worse all the time. Let's do this: if the wind gets up to 60 knots again - and stays there - we go back.'

At about four o'clock on Sunday afternoon, Kooky's requirement for giving up the race was met and surpassed as the wind reached close to 70 knots. By then, the yacht was 90 miles from Eden. In racing terms, the Sword was doing extremely well. Kooky estimated that the Sword was in fifth or sixth place. Even so, he said he was prepared to quit.

'But where are we going to go?' Dags asked. 'We can't head directly to Eden. That would put the waves behind us.'

Hunched over a map, Kooky suggested that they head to the west, which would take them roughly in the direction of Melbourne, until it was safe to turn toward Eden. Actually, he hoped it would be a temporary move. As soon as the wind abated, Kooky intended to resume racing. If the storm ended soon enough and the wind direction changed in the way he believed it would, he thought the Sword might still win the race on adjusted time.

At 4.44pm, Kooky got on the radio and announced the Sword's retirement. He hoped others would make the same decision, in part for their own good and also because it could help the Sword's competitive position if it was later able to rejoin the race.

Dags went back on deck to talk to Glyn about the new course and how to redirect the boat amid the mammoth seas. Glyn already had a plan. 'I'll wait for a big wave,' he said. 'As soon as we're over the top, I'll turn the wheel hard as we go down the other side. There'll be less wind between the waves, and we should be able to get around pretty fast.'

The surface of the sea was light grey, scored by wispy veins of white. The wind was ripping through the rigging, producing a constant high-pitched shrieking that sounded like a distant human voice. Being on the deck was painful. The wind, having created the waves, had gone into battle with them, shaving off the foam at their peaks and creating a jet stream of moisture that looked like smoke. The droplets were hitting Glyn and Dags with skin-stinging speed.

All the waves were huge, but after letting several pass, Glyn, squinting to give the salt water less of an opportunity to punish his eyes, judged one to be larger than the others. 'This is the one,' he shouted. The angle of the Sword increased dramatically as it climbed the wave. Just before it reached the top, Glyn pulled at the wheel, hand over hand. As the Sword passed over the crest and began to tilt forward, the rudder briefly came out of the water, rendering it useless. When it resubmerged a few seconds later, the Sword carved a tight arc on the way downhill, and by the time it reached the valley, it was on a new course.

'Great job,' Dags shouted, exuberantly slapping Glyn on the shoulder. 'That was perfect. Absolutely perfect.'

Glyn said, 'Thanks' but nothing else. A few minutes later, Dags had already begun to worry about Glyn's ability to drive the boat. Rather than steering the westerly course Dags and Glyn had talked about, he was heading north.

'How are you feeling?' Dags asked.

Glyn admitted to feeling terrible and then went on to say how bad he felt about putting in so little time at the wheel. 'I haven't done my job. I've let the team down.'

'No, that's not true. If you're not feeling well, it's not your fault. There's nothing you can do about it.'

The waves were no larger than before the Sword changed course, but they were far more dangerous. The previous course to the south took the Sword almost directly into them. With that angle to the waves, the Sword wouldn't capsize unless it failed to make it over one of them or it was struck by a rogue. The almost northerly course Glyn was steering would take the Sword directly to Eden, but it meant the waves were hitting the yacht from the rear or slightly to the side. The Sword was doing exactly what Dags wanted to avoid - surfing. He thought the speed was dangerous, vastly increasing the chances that it would go out of control and roll upside down.

Glyn wasn't really looking at the waves. Having cinched the cord that tightened the hood on his rain jacket so tightly around his face that it looked as if he were wearing blinders, he seemed to be paying more attention to the instruments.

Dags, not sure what to do, shouted over the wind, 'Do you want me to steer?'

With his eyes focused on the compass, Glyn replied, 'No, I can do it. It makes me feel better.'

Almost pleading, Dags said: 'But you can't steer this way. We have to go into the waves.'

Dags didn't know what to do. He believed Glyn needed to be forcibly told to steer a different course - or he needed to be relieved. It was, Dags thought, a job for Kooky - but he was still below, seemingly chained to the nav station and still more interested in the weather than anything else. He hadn't ventured on deck all day.

'You have to stop surfing,' Dags said. 'Why don't you let someone else steer?'

Glyn said nothing.

Dags wasn't the only crewman who was worried about Glyn's steering. Less than half an hour after they turned around, Brownie decided he had to do something. Each time the Sword picked up speed, he thought the boat was about to spin totally out of control. Twice, he braced himself against rides that he thought would end in capsizing. Furious, he pulled himself up from his bunk and stood on the second step so his head reached into the cockpit. 'Turn into the waves,' he shouted to Glyn. 'You can't do this any more.'

Even though the wheel was just a few feet from the hatch, Glyn and Dags couldn't understand what Brownie was saying, so Dags slid forward in the cockpit until he was sitting near Brownie. 'We have to change course,' Brownie declared. 'It doesn't matter where we're heading - but we can't let the waves hit us like this.'

It was already too late. Before Brownie said another word, a monstrous wave capsized the Sword.

After Dags climbed back on deck and spotted Glyn in the water, his mind was racing with questions. Can he swim to us? Should I swim after him? Should I tie a line around myself first? Can we get the boat to him? Will the engine start?

In fact, not only was the mast gone, but the rigging was under the boat, so turning on the engine, even if it did work, wouldn't have got them very far. The lines that were in the water would wrap around the propeller, stopping the engine. And given what had happened to the wheel, steering would have been impossible. Dags scrambled to throw a life ring toward Glyn, but it went almost nowhere against the wind. Even without a mast or sails, the Sword was being pushed away from Glyn, who, with only his head exposed to the wind, appeared to be almost stationary except for the way he was riding up and down the waves. He wasn't wearing a life preserver. Like everyone else on the Sword, he had been relying on his tether.

'Swim, Glyn!' Dags screamed. 'Come on, Glyn. You can do it. Swim.'

Glyn's eyes were wide open and Dags believed they were focused on him. He assumed Glyn had heard his cries because he began to swim. But he took only six half-strokes, using only his left arm, before he stopped. His face was locked in a grimace, perhaps because of pain or perhaps because he couldn't understand his predicament or why Dags wasn't coming to get him. Dags couldn't believe what he was seeing either. Like yachtsmen everywhere, he had been trained not to swim after someone who had gone overboard, certainly not without being tied to the yacht by a line. The chances that a would-be rescuer can swim to his target and bring him back to safety are too small. But bouncing back and forth on the balls of his feet while keeping his eyes trained on Glyn, Dags believed he had no option but to go in the water.

Brownie was the first man from below to climb on deck. 'Glyn's in the water,' Dags screamed. 'I've got to get him. Get me a long line. I'm going in.'

Although he was already 50ft from the boat, Brownie didn't have any trouble spotting Glyn. He looked small, utterly helpless.

Finding the long lines that controlled the spinnaker, Brownie knotted them together. He tied one end to Dags and the other to the deck. Each of the lines was 80ft long, but Brownie already had second thoughts. By the time Dags swam to Glyn, Brownie thought the lines might not be long enough to cover the rapidly expanding gap between Glyn and the Sword. Even if they were, Brownie worried that their weight could make it impossible for Dags to keep himself and Glyn above water. From the water, it would be difficult for Dags to even see Glyn through the waves. But Dags wanted to go. Immediately. He had been trying to strip off his foul weather gear until he gave up, deciding he didn't have time. Brownie knew that the extra clothing would make it even more difficult to reach Glyn.

'You won't get to him,' Brownie said. 'It's too late.'

'No! I have to go. I have to.'

Dags was bursting with emotional energy. Breathing hard, almost hyperventilating, tears were already rolling down his cheeks. Brownie also felt the weight of what was happening but, recognising that two lives were in his hands, he was trying to be as rational as he could. He thought one life was probably already lost, and he was beginning to believe that Dags, too, would be doomed if he went into the water. After a wave expanded the distance to Glyn by what looked like another 20ft, Brownie was certain. Grabbing the chest straps of Dags's harness, he looked into his friend's eyes.

'You're not going. You'll never get there. There's no way you can get to him.'

Dags realised that Brownie was probably right, and he didn't argue. He just stood near the back of the cockpit, staring at Glyn. By then, several other members of the crew were on the deck, all of them doing the same thing.

Glyn was already having a hard time keeping his head out of the water, and everyone quickly reached the same unthinkable conclusion: Glyn was going to die and there was nothing they could do but watch.

For most of the Sword's crew, there was a strange sense of unreality about all of this, although not because there was anything abstract about it. They could still see Glyn, and they knew how easily they could be in precisely the same position.

Just 10 minutes after the roll, it was becoming more difficult to see Glyn. His head submerged into each of the passing waves, and it seemed to be taking him longer to get back to the surface.

'I can't see him any more,' Dags cried out. 'We're losing him.'

- The Observer

Most viewed

Sydney to Hobart tragedy leaves lasting legacy for sailors and those who raced to help

When this year's Sydney to Hobart fleet sets sail, it will do so bearing the memory of those who lost their lives doing so 20 years ago.

Key points:

- Sailor John Saul recalls waves 25 metres high

- Eden volunteer heard "screaming", desperation on radio

- Tragedy resulted in changes in race weather information

Six sailors died during the 1998 race as a result of some the worst weather conditions seen in the history of the Bluewater Classic.

Hobart-based sailor John Saul was there. He skippered Computerland that year and recalls when the race morphed from sport to survival, and adrenaline took over.

"It's a bit like skidding a car; you don't think about it when the car's skidding, you think about it when the car stops," he said.

Saul recalls his boat being battered by the huge southerly buster which struck the fleet the day after Boxing Day.

Wind gusts reached 90 knots and there were reports of waves 25 metres high.

"We knocked the wind gear off the top of the mast in a wave with a knockdown, broke the safety fence around the side of the boat. A fair few things were falling off," Saul said.

"We were just getting knocked down too much pointing it at Hobart, so we pointed it at New Zealand and she held together."

Computerland managed to navigate to calmer waters and make it to Hobart relatively unscathed.

"We had good people on board. We made good decisions, and we were bloody lucky. Simple as that," he said.

Others were not so fortunate. Tasmanian yacht Business Post Naiad was hammered, and two of its crew would perish.

Another entry, the Winston Churchill, was claimed by the Southern Ocean, taking with it three men. Glyn Charles on Sword of Orion also died.

During the mayhem, 55 sailors were winched to safety, in what remains the largest search and rescue effort in Australian peacetime history.

'You could hear the desperation'

When it became apparent the race was no longer one to Hobart, but one for survival, crews retreated to the New South Wales town of Eden.

Barry Griffiths was working as the divisional commander of the Eden volunteer coastal patrol.

He pulled a 32-hour shift that year, manning radios and helping to coordinate the rescue effort.

"There was a terrible lot of screaming. You could hear the desperation in some of the voices," he said.

"Sometimes their radios went dead, and there could have been a multitude of reasons; [they] were dismasted, some lost power or had too much moisture getting into the radio."

"I reckon looking out the window there that the top of the waves was nearly as high as this window. It was mountainous seas."

Griffiths would be one of a multitude of townspeople whose lives would be changed by the events of '98, as Eden became the centre of the sailing universe.

Kari Esplin is another. She took 16 stricken sailors into her home, providing them with food and shelter.

They slept on the floor of the Esplin family room, and some ended up staying for weeks.

"We couldn't help with the rescue, but we knew people would need warm drinks, dry clothes and a bed to sleep in," she said.

"Sailors were coming in drenched and desperate, and just needed a refuge.

"They were tying their boats down and trying to get everything back together, and at about 3:00am we were back picking up people to bring home so they could get a good night's sleep.

"We are a seafaring town, and we take care of seafarers. It's part of our history, and I've known that since I was a child."

'A sad job'

The events of '98 continue to ripple through the life of crane operator Chris Timms.

After the tragedy, he was given the grisly task of breaking up Business Post Naiad when the insurer declared it unsellable.

It would be a job that would stick with him two decades on.

"Some of the yachts had been out at sea for three or four days, most of them were dismasted," he said.

"I remember B52 was almost broken in half, we had to make a special cradle to lift her out.

"Business Post Naiad was the saddest one.

"It was a sad job, all their personal belongings were on board. I found a wallet belonging to Bruce Guy with a lot of money in it, which we made sure his wife received.

"And Phil Skeggs had bought two nice keyrings with his children's names … I sent them off to Tassie to his family."

'Something we'll never forget'

Out of the tragedy came an inquest which saw a Cruising Yacht Club of Australia (CYCA) race director resign, and the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) increase the depth of its forecasting.

It has become known as the legacy of those who lost their lives in 1998, and has ensured experienced sailors like Skeggs and Guy did not die in vain.

"We've put a lot of work into making sure we've improved on what was already a pretty safe race," CYCA past commodore David Kellett said.

"But if you get those extreme conditions, you have to be ready to face it.

"It's something we think about every time we go through Bass Strait, it's something we will never forget.

"But we've learnt from it and we're much better prepared for it."

On the second day of the race, a minute's silence will be observed by those at sea — remembering those who never made it to port two decades ago.

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related Stories

One man predicted 'six men will be lost overboard', 17 years before sydney to hobart disaster.

When the sea turned, Mike Walker could only look on as his best mate was claimed by the waves

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

YACHT RACING

YACHT RACING; Death Toll Reaches 5 As Storm Ravages Race

By The Associated Press

- Dec. 29, 1998

The Australian Maritime Safety Authority confirmed today that five sailors were dead -- one of them the British Olympian Glyn Charles -- and one remained missing in the wake of Sunday's storm in which 90 mile-an-hour winds and towering seas turned 40-foot yachts into tub toys in the Sydney-to-Hobart yacht race.

Charles, 33, was washed off the Sword of Orion yacht Sunday night and declared drowned today. Race officials said Charles had represented Britain in the Star Class at the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta, where he finished 11th.

''We've taken 54 people off the boats in this race,'' said one of the Authority's officers in charge of operations. ''We've been working 24 hours a day with 10 people on each ship. It's like war in here.''

Royal Australian Navy Aircraft helicopters hovered over 35-foot swells to hoist about 50 other sailors to safety off Australia's southeast coast, 250 miles south of Sydney. Also, 38 civil aircraft and local police and hundred of volunteers took part in the rescue mission.

Many of the sailors were injured -- with broken bones, dislocated shoulders, cuts on the face and hands -- from being struck by broken rigging or tossed upside down when their boats capsized.

Emergency flares sent streams of red smoke to speed the rescue effort.

The 725-mile race continued despite the worst tragedy in its 54-year history. Of the 115 yachts that entered, 59 were forced to seek shelter and several boats were abandoned, race officials said. There was no list of the approximately 1,000 sailors who set off in the race.

The American maxi yacht Sayonara, the 1995 winner, crossed the finish line this morning on the Derwent River at Hobart. Last year's winner, Brindabella, was second with Ragamuffin a seemingly sure third and 35 other boats still competing.

Sayonara's owner, Larry Ellison, the chief executive and founder of Oracle Corporation, was aboard the boat. Oracle is one of the largest computer technology firms in the world, with $8 billion in annual revenue.

Ellison, in tears after battling through the horror of the race, said he had never experienced worse conditions at sea. Asked if he'd come back again, Ellison said, ''My first reaction is not if I live to a thousand years. But who knows?''

Ellison said the race should not have continued: "You know this is not what this is supposed to be about. Difficult yes, dangerous no, life-threatening definitely not. And I think a lot of us are upset."

Said Hugo van Kretschmar, commodore of the host Cruising Yacht Club of Australia in Sydney: ''I don't think less of him because of what he siad. Many people say they won't come back but they keep coming back because it's a real sense of achievement.van Kretschmar had pulled out of the race earlier because of a dead radio.

The Winston Churchill skipper Richard Winning, one of those rescued from a life raft, told of a frantic struggle to stay alive.

''After we got into the life raft and became separated from the others, the damned thing capsized twice on these great seas at night -- which is bloody frightening, let me tell you,'' Winning said. ''I wouldn't want to have spent another night out there.''

The American John Campbell was swept overboard when his yacht capsized. After less than an hour in the water, Campbell was so crippled by hypothermia that a helicopter dropped a policeman down on a line to scoop him up. ''There was a point I didn't think I was going to survive,'' Campbell said.

Some 27 navy ships searched for survivors after the first call of ''Mayday! Mayday! Mayday!'' on radio.

Two Australian sailors were killed when their 40-foot boat, Business Post Naiad, capsized 60 miles off the New South Wales town of Merimbula: the skipper Bruce Guy and the crew member Phil Skeggs. Guy suffered an apparent heart attack during one of the boat's two rollovers and Skeggs drowned when he was unable to release his safety harness.

Their bodies were left on the boat but attempts were being made to recover them as soon as possible, rescue officials said.

''Dad loved sailing,'' said Guy's son, Mark. ''He loved the competition. He also loved a beer and a talk after the race. Dad simply loved life.''

Six crew members from the Winston Churchill were hoisted to safety from two life rafts late Monday, but three others with them -- Jim Lawler, Mike Bannister and John Dean, all from Sydney -- were washed out to sea, rescue officials said.

One man's body was recovered Monday. Officials did not immediately identify the sailor, but believed he was from the Winston Churchill.

Explore Our Weather Coverage

Preparing Your House for the Cold: Here are steps to take to prepare for bitter cold, strong winds and other severe winter conditions at home.

Wind Chill Index: Even if the ambient temperature stays the same, you might feel colder when you are hit by a gust of wind. This is how meteorologists measure the feeling of cold .

On the Road: Safety experts shared some advice on how snow-stranded drivers caught in a snowstorm can keep warm and collected. Their top tip? Be prepared.

Is It Safe to Go Outside?: Heat, flooding and wildfire smoke have made for treacherous conditions. Use this guide to determine when you should stay home .

Climate Change: What’s causing global warming? How can we fix it? Our F.A.Q. tackles your climate questions big and small .

Evacuating Pets: When disaster strikes, household pets’ lives are among the most vulnerable. You can avoid the worst by planning ahead .

Extreme Weather Maps: Track the possibility of extreme weather in the places that are important to you .

- Subscribe Now

- Digital Editions

Sydney-Hobart skipper cleared

The skipper of a boat that sailed past the distressed Sword of Orion during the Sydney-Hobart Race 1998 has been exonerated

The meteorological bomb that hit the Bass Strait during the 1998 Sydney Hobart Race brought tragedy to many, not least the crew of Sword of Orion, the boat from which Britain’s Olympic Star helmsman Glyn Charles was lost.

During the storm, but after a towering wave swept Glyn Charles from the wheel and snapped his harness, the Margaret Rintoul II passed close to the stricken yacht and reported its position but did not stop. After the race, the incident was reported and the investigation has just concluded.

Rule 1.1 of the Racing Rules of Sailing (RRS) ‘requires all boats and competitors to give all possible help to any person or vessel in danger.’ Richard Purcell, the skipper of the Margaret Rintoul II, had not done so.

Having heard all the evidence, the Protest Committee exonerated Purcell, citing that in the light of the extreme weather conditions at the time, and the fact that Margaret Rintoul II’s own engine was no longer working, the decision not to turn back and render direct assistance was appropriate. The Committee did mention deficiencies in radio procedure onboard Margaret Rintoul II but concluded that those deficiencies were not intentional and did not constitute a gross breach of the rule.

“The New South Wales Coroner made his own findings and comments in relation to this incident,” said CYCA Commodore Hans Sommer. “They are not inconsistent with the findings of the Protest Committee, and the criticisms made by him remain part of the record in the Coroner’s Report.”

Terror in the Tasman: Remembering the 1998 Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, 20 years on

It began, as they all do, at 1pm on Boxing Day in Sydney Harbour.

Just 48 hours later, six lives had been lost in what became the deadliest incident in Australian sailing history.

Less than half of all starters made it to the finish line. Some 24 boats were completely abandoned or written off and 55 sailors had to be rescued, by both aircraft and Royal Australian Navy ships. In all, it was our nation’s biggest ever peacetime rescue operation.

Twenty years on from the 1998 edition of the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, Foxsports.com.au looks back at how the terrible tragedy unfolded.

At the starters’ gun, 115 yachts took off through Sydney Harbour and out into the Tasman Sea, to make the 628-nautical mile journey to the south-east of Tasmania.

Yet there were already troubling signs.

A few hours earlier, at the final briefing conducted by the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia, sailors were warned of a low pressure system forming off the coast.

“It’s going to be very hard in Bass Strait, so get ready for a nasty one,” Bob Thomas, navigator and co-owner of AFR Midnight Rambler, told skipper Ed Psaltis in comments reported by Fairfax Media .

Don Buckley, a crew member on B52, spoke to NSW Police a month after the race .

“We had a last-minute update and ... the night before it had been pre-empted that perhaps the low was forming and that would be the only spanner in the works, that we might have some hard stuff,” Buckley said.

“It was hard to know how strong it would be but he (the team’s weather expert) certainly said, ‘you’ll get hammered’.

“Most people expect at some time in the Hobart race you’d have a southerly, and it’s just the cycle of the race. So I guess it didn’t ring any more alarm bells than, OK, it will hit us at some stage.

“We felt comfortable.”

Billionaire tech mogul Larry Ellison, a keen sailor, was skippering the yacht Sayonara, which eventually took line honours. But even he wasn’t expecting to get out as well as they did.

“After what was a beautiful day on Sydney Harbour the wind got more intense and the skies slowly, slowly darkened and I remember after 12 hours we were further ahead than the record holder was in 24 hours,” he told News Corp in 2009 .

“We were going twice as fast as the boat that had set the record on that race and I remember thinking, 'well that’s exciting, but what’s going on?’

“Sayonara was going over 21 knots and I kept saying, she’s not supposed to go that fast. As yet it was just a storm. We really didn’t know what we were getting into at all.”

The leaders began to enter the Bass Strait in the early morning of December 27; even smaller boats were travelling faster than anyone expected.

“It was a very fast ride. Our top speed was 21 knots, surfing a wave on an absolute knife-edge,” Psaltis told Fairfax Media .

“The yacht was going so fast there was a big rooster tail off the stern like a speedboat. We suffered two massive broaches during that period.

“They were really out-of-control capsizes – people in the water, absolute mayhem. Both times the little boat just jumped back up and kept going, showing how strong she was.”

On the 27th, the conditions just continued to worsen.

From 30, to 40, to 50 and then 60 knots in just minutes; the boats were battling horrendous winds, massive waves and the corresponding spray which made things incredibly difficult.

Overnight, some were lucky, like the late Gerry Schipper.

Schipper was a Victorian policeman who became a boat safety advocate after his experience in the 1998 race. His friend Tim Stackpool told ABC’s RN Breakfast in 2015 what happened when he went overboard while sailing on Challenge Again at around 1am.

“In the middle of the night, he was working on deck. He didn’t have any safety gear on; no buoyancy vest, he wasn’t attached to the deck. And he got washed overboard,” Stackpool said.

“He heard the call, ‘man overboard, man overboard’, and he found himself, in the middle of the night, huge seas, and just wondering how this boat was going to come and pick him up.

“He saw it disappearing into the distance, and the waves ... they’re like cliffs. So the boat would disappear and reappear as the waves washed over him.”

With no electronic positioning device - now a necessity for sailors - Schipper was left stranded in stormy seas.

“Then he remembered he had one of waterproof torches in his hand; that’s all he had to signal the crew to come and save him. Because of course they couldn’t see either, it was pitch black.

“He was in the water for half an hour; in the end it was a textbook rescue. They turned the boat around and they almost landed on top of him. They turned around ... so the weather would wash him into the boat.”

Gusts of wind were recorded at terrifying speeds of 90 knots (166km/h) around Wilson’s Promontory with crew members having to battle waves that some estimated reached heights of 30 metres.

“We just felt the boat roar up a wave and I think there were screams from the guy steering - ‘look out’. Then we just went straight over, upside down, and it was mayhem,” Don Buckley later recalled.

“It sounded like a motor accident. Just as loud, it was just horrific.”

After a particularly bad wave, Buckley and the crew tried to recover.

“When it came up it was probably worse than when we went down because we had a lot of water in it, and there was stuff everywhere. I was pinned. I had sailed came down on top of me and I was up to [my] neck in water.

“I was screaming at them to get the sails off me, so I could come out, all I wanted to do was run up the hatch.”

A stove top struck a female crew member in the head and she was trapped underwater. One man got his head stuck in the steering wheel and had to snap himself out of his safety harness; that left him 40 metres away from the boat. Fortunately he was able to swim back to safety.

Others weren’t so lucky. A former British Olympian, Glyn Charles, was swept over board from Sword of Orion and died.

Three men, Mike Bannister, Jim Lawler and John Dean, drowned when their life raft fell apart, following the sinking of their yacht Winston Churchill.

Two perished on Business Post Naiad; the skipper Bruce Guy, who is suspected of suffering a heart attack, and crew member Phil Skeggs who passed from injuries suffered when the boat rolled.

Those who were able to kept sailing towards Hobart; 44 yachts made it. Many others had to try and make their way to Eden, in southern New South Wales.

Barry Griffiths, a member of the Eden volunteer coastal patrol, told the ABC he worked a 32-hour shift to co-ordinate rescues on radios.

“There was a terrible lot of screaming. You could hear the desperation in some of the voices,” he said.

“Sometimes their radios went dead, and there could have been a multitude of reasons; [they] were dismasted, some lost power or had too much moisture getting into the radio.”

“I reckon looking out the window there that the top of the waves was nearly as high as this window. It was mountainous seas.”

Sayonara took line honours at around 8am on December 29 - but the victory celebrations were of course cancelled.

“This is not what racing is supposed to be,” Larry Ellison said after the race.

“Difficult, yes. Dangerous, no. Life-threatening, definitely not. I’d never have signed up for this race if I knew how difficult it would be.”

The billionaire still thinks about 1998.

“I think about it all the time. It was a life-changing experience,” he said a decade later.

“We knew there were boats sinking when we got in, we knew people were in trouble still out there in the midst of it and we were enormously grateful having made it.

“We were the first survivor to get in and finish the race. It was a race for survival, not for victory, trophies or anything like that.”

The 44th and final yacht to arrive, Misty, made it to Hobart on December 31. A day later, on Constitution Dock, a public memorial was held for the six lives lost.

Hugo van Kretschmar, commodore of the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia (who organise the race), read out this statement:

“Mike Bannister, John Dean, Jim Lawler, Glyn Charles, Bruce Guy, Phil Skeggs.

“May the everlasting voyage you have now embarked on be blessed with calm seas and gentle breezes.

“May you never have to reef or change a headsail in the night.

“May your bunk be always warm and dry.”

If the same conditions seen in 1998 were facing the starters of 2018’s race, things would go much differently.

With better weather forecasts and more safety equipment required on board, the yachts would likely avoid the worst of the storm altogether and be better placed to deal with what does eventuate. Rob Kothe, who was on Sword of Orion in 1998, explained part of the difference to Sail World in 2008 .

“At the 12:30pm sked on Dec 27th 1998, the weather forecast read out by race control was winds up to 50 knots,” he said.

“On Sword of Orion we were experiencing 78 knots. Under racing rules we could not tell anyone, because we weren’t allowed to give other boats assistance by informing them of the weather ahead.

“We decided this was a life and death situation; it was not a game. We broke the rules to report to the wind strengths to the fleet, which soon reached 92 knots.

“It was too late to warn everyone. Many boats were close behind us, but about 40 boats retired to Eden as a result of our actions.

“Under today’s more sensible rules wind speeds above 40 knots have to be reported; therefore sudden unpredicted storm cells will not catch everyone unawares.

“Across the board, the equipment has improved, including better life jackets, better harnesses, personal EPIRBS. There’s also much better education and training. Better weather data and a change in the mind set of Race officials and race participants have made the biggest change, but all these moves have made racing safer.”

The tragic circumstances of 1998 have therefore helped save lives since then.

Twenty years on, a moment’s silence will be performed on race radio to remember the fallen.

- CLASSIFIEDS

- NEWSLETTERS

- SUBMIT NEWS

New 'Sword of Orion' - For Hobart Race Survivor

Related Articles

- CLASSIFIEDS

- NEWSLETTERS

- SUBMIT NEWS

Boats for sale

Sword of Orion triumphs in five hour match race.

Related articles.

The global authority in superyachting

- NEWSLETTERS

- Yachts Home

- The Superyacht Directory

- Yacht Reports

- Brokerage News

- The largest yachts in the world

- The Register

- Yacht Advice

- Yacht Design

- 12m to 24m yachts

- Monaco Yacht Show

- Builder Directory

- Designer Directory

- Interior Design Directory

- Naval Architect Directory

- Yachts for sale home

- Motor yachts

- Sailing yachts

- Explorer yachts

- Classic yachts

- Sale Broker Directory

- Charter Home

- Yachts for Charter

- Charter Destinations

- Charter Broker Directory

- Destinations Home

- Mediterranean

- South Pacific

- Rest of the World

- Boat Life Home

- Owners' Experiences

- Interiors Suppliers

- Owners' Club

- Captains' Club

- BOAT Showcase

- Boat Presents

- Events Home

- World Superyacht Awards

- Superyacht Design Festival

- Design and Innovation Awards

- Young Designer of the Year Award

- Artistry and Craft Awards

- Explorer Yachts Summit

- Ocean Talks

- The Ocean Awards

- BOAT Connect

- Between the bays

- Golf Invitational

- Boat Pro Home

- Pricing Plan

- Superyacht Insight

- Product Features

- Premium Content

- Testimonials

- Global Order Book

- Tenders & Equipment

Orion One: New details of Orion Yachts' in-build 43m motor yacht revealed

Yalova-based Orion Yachts and Red Yacht Design have offered a first look inside the 43-metre superyacht Orion One as it approaches completion.

Construction began in 2022 with Orion One's hull and superstructure now "almost finished". The launch is scheduled for the end of 2024.

Red Yacht Design is responsible for the interior and exterior design of the 480GT yacht, giving her an elegant flared bow, cascading aft decks and generous lines of glazing. New interior imagery reveals the use of light woods and a neutral colour scheme offset by "aquamarine" and "emerald" details.

"The choice of light colours, the playful infusion of tones, and the thoughtful incorporation of contemporary elements aim to provide a serene yet dynamic setting for discerning yacht enthusiasts," added Cana Gokhan of Red Yacht Design.

There is a total of five cabins including the owner's cabin, arranged in a way that makes Orion One suitable for use as a private charter yacht .

Naval architecture on the new yacht has been completed by Alfa Marine Engineering. Special consideration has been given to the use of al fresco areas, with key features including a foredeck sunpad area and Portuguese bridge, plus a sundeck with a unique waterfall installation that feeds water into the dip pool.

Orion One will be the first vessel built under the Orion Yachts brand. The brand is the superyacht branch of Hersek Gemi .

More stories

Most popular, from our partners, sponsored listings.

- Show Spoilers

- Night Vision

- Sticky Header

- Highlight Links

Follow TV Tropes

http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Recap/SportsNightS01E18TheSwordOfOrion

Recap / Sports Night S 01 E 18 The Sword Of Orion

Edit locked.

Directed by Robert Berlinger

Written by David Handelman , Mark McKinney , Aaron Sorkin , & Joan Binder Weiss (uncredited)

Jeremy comes back from his trip to his parents, but seems more interested in doing a story about a famous shipwreck than telling Natalie what happened with his visit. Dan tries to get Rebecca to watch a baseball game with him.

- Author Appeal : This won't be the last time an Aaron Sorkin show works in a joke about time zones .

- Also, Dan's interest in sailing and boats comes through when he explains what the Governor's Cup is.

- Department of Redundancy Department : Dan: Did Orlando Rojas pitch this afternoon? Natalie: That's a good question. Dan: Thank you very much. Did he pitch this afternoon?

- Does This Remind You of Anything? : Jeremy's trying to figure out what went wrong with the Sword of Orion in the same way he's trying to figure out his father's transgression.

- Get Out! : Rebecca: Dan, do you see that I have work to do? Dan: I see that you have work to do but I'm not entirely convinced that you know what it is. Rebecca: Get out.

- Hypocritical Humor : Natalie: You wanna know how good I am? I'm not even gonna ask why you didn't call. Jeremy: Thank you, 'cause what I really gotta do right now is get a hold of- Natalie: Why the hell didn't you call?

- Title Drop : The Sword of Orion is the name of a yacht that steered off course into a storm ten years earlier during the Governor's Cup. Jeremy wants to do a piece on it.

- Sports Night S 01 E 17 How Are Things In Gloca Morra

- Recap/Sports Night

- Sports Night S 01 E 19 Elis Coming

Important Links

- Action Adventure

- Commercials

- Crime & Punishment

- Professional Wrestling

- Speculative Fiction

- Sports Story

- Animation (Western)

- Music And Sound Effects

- Print Media

- Sequential Art

- Tabletop Games

- Applied Phlebotinum

- Characterization

- Characters As Device

- Narrative Devices

- British Telly

- The Contributors

- Creator Speak

- Derivative Works

- Laws And Formulas

- Show Business

- Split Personality

- Truth And Lies

- Truth In Television

- Fate And Prophecy

- Edit Reasons

- Isolated Pages

- Images List

- Recent Videos

- Crowner Activity

- Un-typed Pages

- Recent Page Type Changes

- Trope Entry

- Character Sheet

- Playing With

- Creating New Redirects

- Cross Wicking

- Tips for Editing

- Text Formatting Rules

- Handling Spoilers

- Administrivia

- Trope Repair Shop

- Image Pickin'

Advertisement:

Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race 2023

Dresdner Sword of Orion

Competitor details.

- Line Honours

Full Standings available approximately three hours after the start.

OFFICIAL ROLEX SYDNEY HOBART MERCHANDISE

Shop the official clothing range of the Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race and the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia in person at the Club in New South Head Road, Darling Point or online below.

From casual to technical clothing, there is something for all occasions. Be quick as stock is limited!

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Sydney to Hobart 1998 tragedy, 20 years on: Sword of Orion skipper Rob Kothe speaks. By Tim Elbra. Dec 25th, 2018. ... At the yacht's helm as it turned back was Glyn Charles, ...

Sword of Orion was flipped on its side as if it were nothing more than a balsawood model. Its mast hit the water below 90 degrees and the yacht plunged on its side down a curling 50m face.

The yacht, Sword of Orion, abandoned after losing its mast. Credit: Andrew Taylor Mr Winning and three crewmates were rescued virtually unharmed from their life raft on Monday evening.

By then, the yacht was 90 miles from the safe haven of Eden. In racing terms, Sword of Orion was still doing well, but even so he told his shipmate Kulmar he was prepared to give up. 'It's up ...

The 1998 Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race was the 54th annual running of the "blue water classic" Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race. It was hosted by the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia based in Sydney, ... 28 December 1998); and Glyn Charles (Sword of Orion, drowned, 27 December 1998).

Glyn Charles didn't see the 40ft wall of water until it was too late. It had approached the Sword of Orion from behind, slightly from the port side, and seconds after the yacht began to ride up ...

Glyn Charles on Sword of Orion also died. During the mayhem, 55 sailors were winched to safety, in what remains the largest search and rescue effort in Australian peacetime history. 'You could ...

Tasmanian yacht Business Post Naiad was hammered, and two of its crew would perish. ... Glyn Charles on Sword of Orion also died. During the mayhem, 55 sailors were winched to safety, in what ...

In the 1998 Sydney to Hobart race, six men lost their lives, 30 civil and military aircraft helped rescue 55 sailors from 12 stricken yachts, five boats sank and seven were abandoned. Just 44 of ...

Charles, 33, was washed off the Sword of Orion yacht Sunday night and declared drowned today. Race officials said Charles had represented Britain in the Star Class at the 1996 Summer Olympics in ...

Shop the official clothing range of the Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race and the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia in person at the Club in New South Head Road, Darling Point or online below. From casual to technical clothing, there is something for all occasions. Be quick as stock is limited! BUY NOW

The skipper of a boat that sailed past the distressed Sword of Orion during the Sydney-Hobart Race 1998 has been exonerated. The meteorological bomb that hit the Bass Strait during the 1998 Sydney Hobart Race brought tragedy to many, not least the crew of Sword of Orion, the boat from which Britain's Olympic Star helmsman Glyn Charles was lost.

Rob Kothe, who was on Sword of Orion in 1998, explained part of the difference to Sail World in 2008. "At the 12:30pm sked on Dec 27th 1998, the weather forecast read out by race control was ...

British Olympic Star sailor Glyn Charles, in Australia to compete at the 1999 world championships in Melbourne, died after being swept overboard from the Sydney yacht Sword of Orion. SAILING ...

The Cruising Yacht Club of Australia released the Report, Findings and Recommendations of the 1998 Sydney to Hobart Race Review Committee - and announced that it had already made substantial progress towards implementing the majority of the recommendations. ... The Committee investigated reports from Sword of Orion of a yacht not responding to ...

by Peter Campbell on 8 Mar 1999. Rob Kothe, rescued from his sinking yacht Sword of Orion in the tragic Telstra Sydney to Hobart, is returning to ocean racing with a new Sword of Orion. The yacht, the Sydney AC 40 which previously raced as Sharp Hawke 5, will make its debut under Kothe's ownership in this month's Sydney - Mooloolaba race.

The Yachts; 1999; Sword of Orion; Sword of Orion . Competitor Details. Yacht Name: Sword of Orion: Sail Number: 2006: Owner: Rob Kothe: Skipper: Rob Kothe: State: NSW: Club: CYCA: CYCA SHOP. OFFICIAL ROLEX SYDNEY HOBART MERCHANDISE. Shop the official clothing range of the Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race and the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia.

Rob Kothe's high performance Sydney 40 Sword of Orion revelled in a moderating 12-15 knot South East wind to win the IMS class match race over Wayne Millar's sloop Zoe in the Joico Big Boat series.

Shop the official clothing range of the Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race and the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia in person at the Club in New South Head Road, Darling Point or online below. From casual to technical clothing, there is something for all occasions.

10 January 2024 • Written by Katia Damborsky. Yalova-based Orion Yachts and Red Yacht Design have offered a first look inside the 43-metre superyacht Orion One as it approaches completion. Construction began in 2022 with Orion One's hull and superstructure now "almost finished". The launch is scheduled for the end of 2024.

Sports Night S 01 E 18 The Sword Of Orion. Written by David Handelman, Mark McKinney, Aaron Sorkin, & Joan Binder Weiss (uncredited) Jeremy comes back from his trip to his parents, but seems more interested in doing a story about a famous shipwreck than telling Natalie what happened with his visit. Dan tries to get Rebecca to watch a baseball ...