Currency: GBP

- Worldwide Delivery

Mooring Warps and Mooring Lines

- LIROS 3 Strand Polyester Mooring Warps

- LIROS Braided Dockline Mooring Warps

- LIROS Classic Mooring Warps

- LIROS Green Wave 3 Strand Mooring Warps

- LIROS Handy Elastic Mooring Warps

- LIROS Moorex12 Mooring Warps

- LIROS Octoplait Polyester Mooring Warps

- LIROS Polypropylene Floating Mooring Warps

- LIROS Super Yacht Mooring Polyester Docklines

- Marlow Blue Ocean Dockline

Mooring Accessories

- Mooring Cleats and Fairleads

- Mooring Compensators

- Mooring Shackles

- Mooring Swivels

Mooring Strops

- LIROS 3 Strand Nylon Mooring Strops

- LIROS Anchorplait Nylon Mooring Strops

- Small Boat and RIB Mooring Strops

Mooring Bridles

- V shape Mooring Bridles

- Y shape Mooring Bridles

Mooring Strops with chain centre section

- 3 Strand / Chain / 3 Strand

- Anchorplait / Chain / Anchorplait

Bonomi Mooring Cleats

- Majoni Fenders

- Polyform Norway Fenders

- Dock Fenders

- Fender Ropes and Accessories

- Ocean Inflatable Fenders

Mooring Buoys

Max power bow thrusters.

- Coastline Bow Thruster Accessories

50 metre / 100 metre Rates - Mooring

Mooring information.

- Mooring Warps Size Guide

- Mooring Lines - LIROS Recommended Diameters

- Mooring Rope Selection Guide

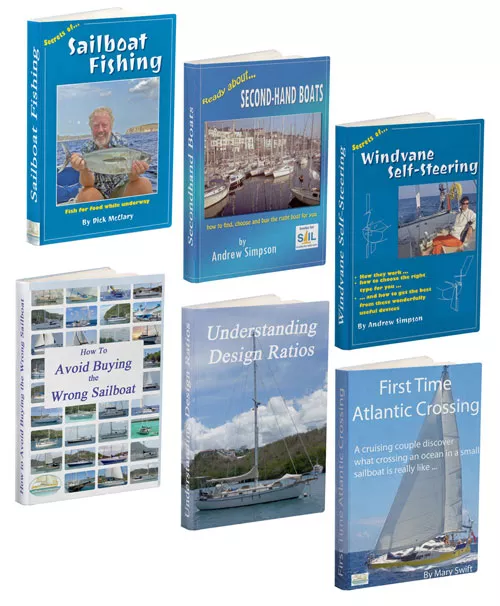

- Mooring Warp Length and Configuration Guide

- How to estimate the length of a single line Mooring Strop

- Mooring Ropes - Break Load Chart

- Mooring Compensator Advisory

- Rope Cockling Information

- Fender Size Guide

- Majoni Fender Guide

- Polyform Norway Fender Inflation Guide

Custom Build Instructions

- More Article and Guides >

Anchor Warps Spliced to Chain

- LIROS 3 Strand Nylon Spliced to Chain

- LIROS 3 Strand Polyester Spliced to Chain

- LIROS Anchorplait Nylon Spliced to Chain

- LIROS Octoplait Polyester Spliced to Chain

Anchor Warps

- Leaded Anchor Warp

- LIROS 3 Strand Nylon Anchor Warps

- LIROS 3 Strand Polyester Anchor Warps

- LIROS Anchorplait Nylon Anchor Warps

- LIROS Octoplait Polyester Anchor Warps

- Aluminium Anchors

- Galvanised Anchors

- Stainless Steel Anchors

Calibrated Anchor Chain

- Cromox G6 Stainless Steel Chain

- G4 Calibrated Stainless Steel Anchor Chain

- Lofrans Grade 40

- MF DAMS Grade 70

- MF Grade 40

- Titan Grade 43

Clearance Chain

Anchoring accessories.

- Anchor Connectors

- Anchor Trip Hooks and Rings

- Anchoring Shackles

- Bow Rollers and Fittings

- Chain and Anchor Stoppers

- Chain Links and Markers

50 / 100 metre Rates - Anchoring

Chain snubbers.

- Chain Hooks, Grabs and Grippers

- Chain Snubbing Bridles

- Chain Snubbing Strops

Drogue Warps and Bridles

- Lewmar Windlasses

- Lofrans Windlasses

- Maxwell Windlasses

- Quick Windlasses

Windlass Accessories

- Coastline Windlass Accessories

- Lewmar Windlass Accessories

- Lofrans Windlass Accessories

- Lofrans Windlass Replacement Parts

- Maxwell Windlass Accessories

- Quick Windlass Accessories

Anchoring Information

- How To Choose A Main Anchor

- Anchoring System Assessment

- Anchor Chain and Rope Size Guide

- The Jimmy Green Guide to the Best Anchor Ropes

- What Size Anchor Do I Need?

- Anchor Size Guides

- Anchor Rope Break Load and Chain Compatibility Chart

- How to Choose Your Anchor Chain

- How to Establish the Correct Anchor Chain Calibration?

- Calibrated Anchor Chain - General Information

- Calibrated Anchor Chain Quality Control

- Calibrated Chain - Break Load and Weight Guide

- Galvanising - Managing Performance and Endurance expectation

- Can Galvanised Steel be used with Stainless Steel?

- Windlass Selection Guide

- More Articles and Guides

Stainless Steel Wire Rigging and Wire Rope

- 1x19 Wire Rigging

- 7x19 Flexible Wire Rigging

- Compacted Strand Wire Rigging

- Insulated 1x19 Wire Backstays

Wire Rigging Fittings

- Swaged Terminals

- Swageless Terminals

- Turnbuckles / Rigging screws

- Turnbuckle Components

- Backstay Insulators

- Wire Terminals

Rigging Accessories

- Backing Plates

- Backstay Adjuster and Fittings

- Backstay Blocks

- Pins, Rings and Nuts

- Rigging Chafe Protection

Fibre Rigging

- DynIce Dux Fibre Rigging

- LIROS D-Pro Static Rigging

- LIROS D-Pro-XTR Fibre Rigging

- Marlow Excel D12 MAX 78 Rigging

- Marlow M-Rig Max Rigging

Fibre Rigging Fittings

- Bluewave Rope Terminals

- Colligo Marine Terminals

Dinghy Rigging

- Dinghy Rigging Fittings

- Fibre Dinghy Rigging

- Stainless Steel Dinghy Rigging

Wind Indicators

Guard wires, guardrails and guardrail webbing.

- Guard Rail Fittings

- Guard Rails in Fibre and Webbing

- Guard Wire Accessories

- Guard Wires

Furling Systems

- Anti-torsion Stays

- Headsail Reefing Furlers

- Straight Luff Furlers

- Top Down Furlers

Furling Accessories

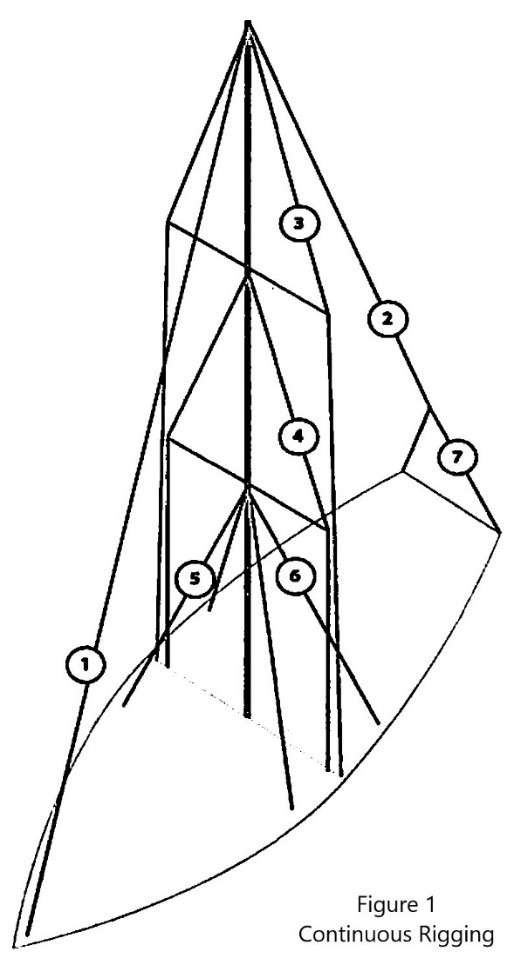

- Continuous Furling Line Accessories

- Furling Line Accessories

50 / 100 metre Rates - Wire and Fibre

Standing rigging assistance.

- More Articles and Guides >

- Cruising Halyards

- Performance Halyards

- Dinghy Halyards

Rigging Shackles

- Bronze Snap Shackles

- Captive and Key Pin Shackles

- hamma™ Snap Shackles

- Selden Snap Shackles

- Soft Shackles

- Standard Snap Shackles

- Tylaska End Fittings

- Wichard Snap Shackles

Lashing, Lacing and Lanyards

- LIROS 3 Strand Lashing, Lacing and Lanyards

- LIROS Braided Lashing, Lacing and Lanyards

- Cruising Sheets

- Performance Sheets

- Dinghy Sheets

- Continuous Sheets

- Tapered Sheets

Running Rigging Accessories

- Anti-Chafe Rope Protection

- Barton Sail Handling

- Lazy Jack Sail Handling

- Rodkickers, Boomstruts

- Sail Handling Accessories

- Slab Reefing

Shock Cord and Fittings

Control lines.

- Cruising Control Lines

- Performance Control Lines

- Dinghy Control Lines

- Continuous Control Lines

Classic Ropes

- 50 / 100 metres - Classic

- Classic Control Lines

- Classic Docklines

- Classic Halyards

- Classic Sheets

- LIROS Classic 3 Strand Polyester

50 / 100 metre Rates - Running Rigging

- 50 / 100 metres - Cruising Ropes

- 50 / 100 metres - Dinghy Ropes

- 50 / 100 metres - Lashing and Lanyards

- 50 / 100 metres - Performance Ropes

- LIROS Ropes

- Marlow Ropes

Running Rigging Resources

- Running Rigging Rope Fibres and Construction Explained

- How to Select a Suitable Halyard Rope

- How to select Sheets and Guys

- Dyneema Rope - Cruising and Racing Comparison

- Dinghy Rope Selection Guide

- Rope Measurement Information

- Running Rigging - LIROS Recommended Line Diameters

- Running Rigging Break Load Comparison Chart

- Colour Coding for Running Rigging

- Selecting the right type of block, plain, roller or ball bearing

- Replacing your Furling Line

- Recycling Rope

Running Rigging Glossary

Custom build instructions for sheets, halyards, control lines, low friction rings, plain bearing blocks.

- Barton Blocks

- Harken Element Blocks

- Seasure 25mm Blocks

- Selden Yacht Blocks

Wooden Blocks

Ball bearing blocks.

- Barton Ball Bearing Blocks

- Harken Ball Bearing Blocks

- Holt Dynamic Blocks

- Selden Ball Bearing Blocks

Ratchet Blocks

- Harken Ratchet Blocks

- Selden Ratchet Blocks

Roller Bearing Blocks

- Harken Black Magic Blocks

- Selden Roller Bearing Blocks

Clutches and Organisers

- Barton Clutches and Organisers

- Lewmar Clutches

- Spinlock Clutches and Organisers

Genoa Car Systems

- Barton Genoa Sheeting

- Harken Genoa Systems

- Lewmar HTX Genoa Systems

Traveller Systems

- Barton Traveller Systems

- Harken Traveller Systems

Deck Fittings

- Bungs and Hatches

- Bushes and Fairleads

- Deck Eyes, Straps and Hooks

- Pad Eyes, U Bolts and Eye Bolts

Rudder and Transom Fittings

- Pintles and Gudgeons

- Tiller Extensions and Joints

Stanchion Blocks and Fairleads

Snatch blocks.

- Barton K Cam Cleats

- Harken Ball Bearing Cam Cleats

- Holt Cam Cleats

- Selden Cam Cleats

- Spinlock PXR Cleats

Block and Tackle Purchase Systems

- Barton Winches, Snubbers and Winchers

- Coastline Electric Winch Accessories

- Harken Winches, Handles and Accessories

- Karver Winches

- Lewmar Winches, Handles and Accessories

- Winch Servicing and Accessories

Deck Hardware Support

- Blocks and Pulleys Selection Guide

- Barton High Load Eyes

- Dyneema Low Friction Rings Comparison

- Seldén Block Selection Guide

- Barton Track Selection Guide

- Barton Traveller Systems Selection Guide

- Harken Winch Selection Guide

- Karver Winch Comparison Chart

- Lewmar Winch Selection Guide - PDF

- Winch Servicing Guide

Sailing Flags

- Courtesy Flags

- Red Ensigns

- Blue Ensigns

- Flag Accessories

- Flag Staffs and Sockets

- Flag Making and Repair

- Signal Code Flags

- Galvanised Shackles

- Stainless Steel Shackles

- Titanium Shackles

- Webbing only

- Webbing Restraint Straps

- Webbing Sail Ties

- Webbing Soft Shackles

Hatches and Portlights

Sail care and repair.

- Sail Sewing

Maintenance

- Antifouling

- Fillers and Sealants

- Primers and Thinners

- PROtect Tape

Fixings and Fastenings

- Monel Rivets

- Screws, Bolts, Nuts and Washers

- U Bolts, Eye Bolts and Pad Eyes

Splicing Accessories

- Fids and Tools

- Knives and Scissors

General Chandlery

- Barrier Ropes

- Canvas Bags and Accessories

- Carabiners and Hooks

- Netting and Accessories

- Rope Ladders

Seago Boats and Tenders

Chandlery information, flag articles.

- Flag Size Guide

- Bending and Hoisting Methods for Sailing Flags

- Courtesy Flags Identification, Labelling and Stowage

- Courtesy Flag Map

- Flag Etiquette and Information

- Glossary of Flag Terms and Parts of a Flag

- Making and Repairing Flags

- Signal Code Message Definitions

Other Chandlery Articles

- Anchorplait Splicing Instructions

- Antifoul Coverage Information

- Hawk Wind Indicator Selection Guide

- Petersen Stainless - Upset Forging Information

- Speedy Stitcher Sewing Instructions

- Thimble Dimensions and Compatible Shackles

Jackstays and Jacklines

- Webbing Jackstays

- Stainless Steel Wire Jackstay Lifelines

- Fibre Jackstay Lifelines

- Jackstay and Lifeline Accessories

Safety Lines

Lifejackets.

- Children's Life Jackets

- Crewsaver Lifejackets

- Seago Lifejackets

- Spinlock Lifejackets

Buoyancy Aids

Life jackets accessories.

- Lifejacket Lights

- Lifejacket Rearming Kits

- Lifejacket Spray Hoods

Overboard Recovery

- Lifebuoy Accessories

- Purchase Systems

- Slings and Throwlines

Floating Rope

- LIROS Multifilament White Polypropylene

- LIROS Yellow Floating Safety Rope

- Danbuoy Accessories

- Jimmy Green Danbuoys

- Jonbuoy Danbuoys

- Seago Danbuoys

- Liferaft Accessories

- Seago Liferafts

Safety Accessories

- Fire Safety

- Grab Bag Contents

- Grab Bags and Polybottles

- Handheld VHF Radios

- Sea Anchors and Drogues

Safety Resources

- Guard Wires - Inspection and Replacement Guidance

- Guard Wire Stud Terminal Dimensions

- Webbing Jackstays Guidance

- Webbing Jackstays - Custom Build Instructions

- Danbuoy Selection Guide

- Danbuoy Instructions - 3 piece Telescopic - Offshore

- Liferaft Selection Guide

- Liferaft Servicing

- Man Overboard Equipment - World Sailing Compliance

- Marine Safety Information Links

- Safety Marine Equipment List for UK Pleasure Vessels

Sailing Clothing

- Sailing Jackets

- Sailing Trousers

- Thermal Layers

Leisure Wear

- Accessories

- Rain Jackets

- Sweatshirts

Sailing Footwear

- Dinghy Boots and Shoes

- Sailing Wellies

Leisure Footwear

- Walking Shoes

Sailing Accessories

- Sailing Bags and Holdalls

- Sailing Gloves

- Sailing Kneepads

Clothing Clearance

Clothing guide.

- What to wear Sailing

- Helly Hansen Mens Jacket and Pant Size Guide

- Helly Hansen Womens Sailing Jacket and Pant Size Guide

- Lazy Jacks Mens and Womens Size Charts

- Musto Men's and Women's Size Charts

- Old Guys Rule Size Guide

- Sailing Gloves Size Guides

- Weird Fish Clothing Size Charts

The Jimmy Green Clothing Store

Lower Fore St, Beer, East Devon, EX12 3EG

- Adria Bandiere

- Anchor Marine

- Anchor Right

- August Race

- Barton Marine

- Blue Performance

- Brierley Lifting

- Brook International

- Brookes & Adams

- Captain Currey

- Chaineries Limousines

- Coastline Technology

- Colligo Marine

- Cyclops Marine

- Douglas Marine

- Ecoworks Marine

- Exposure OLAS

- Fire Safety Stick

- Fortress Marine Anchors

- Hawk Marine Products

- Helly Hansen

- International

- Jimmy Green Marine

- Maillon Rapide

- Mantus Marine

- Marling Leek

- Meridian Zero

- MF Catenificio

- Ocean Fenders

- Ocean Safety

- Old Guys Rule

- Petersen Stainless

- Polyform Norway

- PSP Marine Tape

- Sidermarine

- Stewart Manufacturing Inc

- Team McLube

- Technical Marine Supplies

- Titan Marine (CMP)

- Ultramarine

- Waterline Design

- William Hackett

Clearance August Race Boat Cleaning Kit £26.00

Clearance LIROS Racer Dyneema £55.08

Clearance Folding Stock Anchor £123.25

Clearance LIROS Herkules £0.00

Clearance Barton Size 0 Ball Bearing Blocks - 5mm £10.13

Clearance Marlow Blue Ocean® Doublebraid £18.48

Mooring Clearance

Anchoring clearance, standing rigging clearance, running rigging clearance, deck hardware clearance, chandlery clearance, safety clearance, sailboat rigging can be divided in to 2 categories:.

Standing Rigging - the wires and ropes that hold up the mast, also known as shrouds or stays.

Running Rigging - the ropes (and wires) that control the sails on a yacht.

There are a large number of different terms that cover the use for which each rope is employed.

The most common generic terms are sheets and halyards.

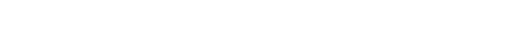

Normally attached to the clew of the sail and control the shape and angle to the wind - each individual sheet is identified by the name of the sail as a prefix e.g. Jib sheets, genoa sheets, yankee sheets, staysail sheets, code zero sheets, gennaker sheets, cruising chute sheets, mainsheets, mizzen sheets - where these are a pair, they may also be classified as port or starboard. Spinnaker Sheets are used in conjunction with Spinnaker Guys and a spinnaker pole to control the shape of the spinnaker on either gybe.

Attached to the head of a sail and used to haul a sail up the mast - in the same way as sheets, each halyard is identified by the name of the sail as a prefix e.g. main halyard.

Sheets and halyards are part of a more generic category: Control Lines or a little more obscurely, Preventers. Control Lines include sheets and halyards and all the other ropes and wires that contribute to the efficient mangement of a yacht's sail area. A rope that stops an accidental gybe is commonly referred to as a preventer. However, most of the ropes that comprise a yacht's running rigging can be described as preventers i.e. a rope that is preventing something or control lines i.e. a rope that is controlling something.

Control Lines:

Tack Line - attached to the tack of a sail to make the length of the luff adjustable - common on loose footed reaching/running headsails e.g. gennakers but also used on more traditional rigs e.g. dipping lugsails

In Hauler or Tweaker - attached to a headsail (jib/genoa/yankee/code zero) sheet and used to bring the angle of the lead nearer to the centreline than the normal setting.

Barber Hauler - attached to a headsail sheet and used to create more downward pressure and generally from a point further outboard than the normal fairlead setting.

Downhaul or Cunningham - attached to the tack of a mainsail and used to create tension in the luff.

Kicker or Vang - diagonal line or purchase system (block and tackle) from base of mast to a point on the underside of the boom - used to create downward tension on the boom and subsequently the leach of the sail.

Outhaul - generally attached to the clew of a mainsail to adjust the foot tension.

Reefing Line or Reefing Pennant - Lines reeved through the boom and the mainsail to facilitate a reduction in mainsail area.

Lazyjack Line - used for guiding and controlling the mainsail as it is dropped.

Running Backstays or Checkstays - adjustable version of the backstay, generally consisting of a very low stretch standing part (single line) attached to a purchase system for adjusting the tension.

Preventer - line deployed to prevent the mainsail boom from accidentally gybing or control the speed of the boom's transition during a gybe.

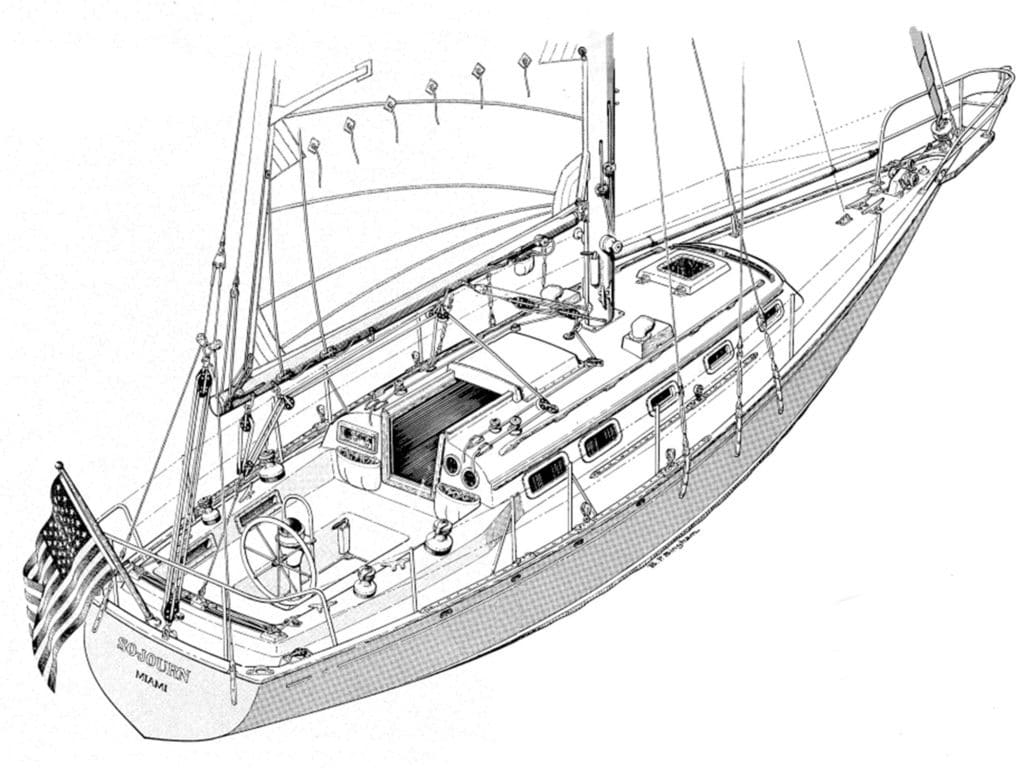

- Types of Sailboats

- Parts of a Sailboat

- Cruising Boats

- Small Sailboats

- Design Basics

- Sailboats under 30'

- Sailboats 30'-35

- Sailboats 35'-40'

- Sailboats 40'-45'

- Sailboats 45'-50'

- Sailboats 50'-55'

- Sailboats over 55'

- Masts & Spars

- Knots, Bends & Hitches

- The 12v Energy Equation

- Electronics & Instrumentation

- Build Your Own Boat

- Buying a Used Boat

- Choosing Accessories

- Living on a Boat

- Cruising Offshore

- Sailing in the Caribbean

- Anchoring Skills

- Sailing Authors & Their Writings

- Mary's Journal

- Nautical Terms

- Cruising Sailboats for Sale

- List your Boat for Sale Here!

- Used Sailing Equipment for Sale

- Sell Your Unwanted Gear

- Sailing eBooks: Download them here!

- Your Sailboats

- Your Sailing Stories

- Your Fishing Stories

- Advertising

- What's New?

- Chartering a Sailboat

- Running Rigging

Sailboat Rigging: Part 2 - Running Rigging

Sailboat rigging can be described as being either running rigging which is adjustable and controls the sails - or standing rigging, which fixed and is there to support the mast. And there's a huge amount of it on the average cruising boat...

- Port and starboard sheets for the jib, plus two more for the staysail (in the case of a cutter rig) plus a halyard for each - that's 6 separate lines;

- In the case of a cutter you'll need port and starboard runners - that's 2 more;

- A jib furling line - 1 more;

- An up-haul, down-haul and a guy for the whisker pole - 3 more;

- A tackline, sheet and halyard for the cruising chute if you have one - another 3;

- A mainsheet, halyard, kicker, clew outhaul, topping lift and probably three reefing pennants for the mainsail (unless you have an in-mast or in-boom furling system) - 8 more.

Total? 23 separate lines for a cutter-rigged boat, 18 for a sloop. Either way, that's a lot of string for setting and trimming the sails.

Many skippers prefer to have all running rigging brought back to the cockpit - clearly a safer option than having to operate halyards and reefing lines at the mast. The downside is that the turning blocks at the mast cause friction and associated wear and tear on the lines.

The Essential Properties of Lines for Running Rigging

It's often under high load, so it needs to have a high tensile strength and minimal stretch.

It will run around blocks, be secured in jammers and self-tailing winches and be wrapped around cleats, so good chafe resistance is essential.

Finally it needs to be kind to the hands so a soft pliable line will be much more pleasant to use than a hard rough one.

Not all running rigging is highly stressed of course; lines for headsail roller reefing and mainsail furling systems are comparatively lightly loaded, as are mainsail jiffy reefing pennants, single-line reefing systems and lazy jacks .

But a fully cranked-up sail puts its halyard under enormous load. Any stretch in the halyard would allow the sail to sag and loose its shape.

It used to be that wire halyards with spliced-on rope tails to ease handling were the only way of providing the necessary stress/strain properties for halyards.

Thankfully those days are astern of us - running rigging has moved on a great deal in recent years, as have the winches, jammers and other hardware associated with it.

Modern Materials

Ropes made from modern hi-tech fibres such as Spectra or Dyneema are as strong as wire, lighter than polyester ropes and are virtually stretch free. It's only the core that is made from the hi-tech material; the outer covering is abrasion and UV resistant braided polyester.

But there are a few issues with them:~

- They don't like being bent through a tight radius. A bowline or any other knot will reduce their strength significantly;

- For the same reason, sheaves must have a diameter of at least eight times the diameter of the line;

- Splicing securely to shackles or other rigging hardware is difficult to achieve, as it's slippery stuff. Best to get these done by a professional rigger...

- As you may have guessed, it's expensive stuff!

My approach on Alacazam is to use Dyneema cored line for all applications that are under load for long periods of time - the jib halyard, staysail halyard, main halyard, spinnaker halyard, kicking strap and checkstays - and pre-stretched polyester braid-on-braid line for all other running rigging applications.

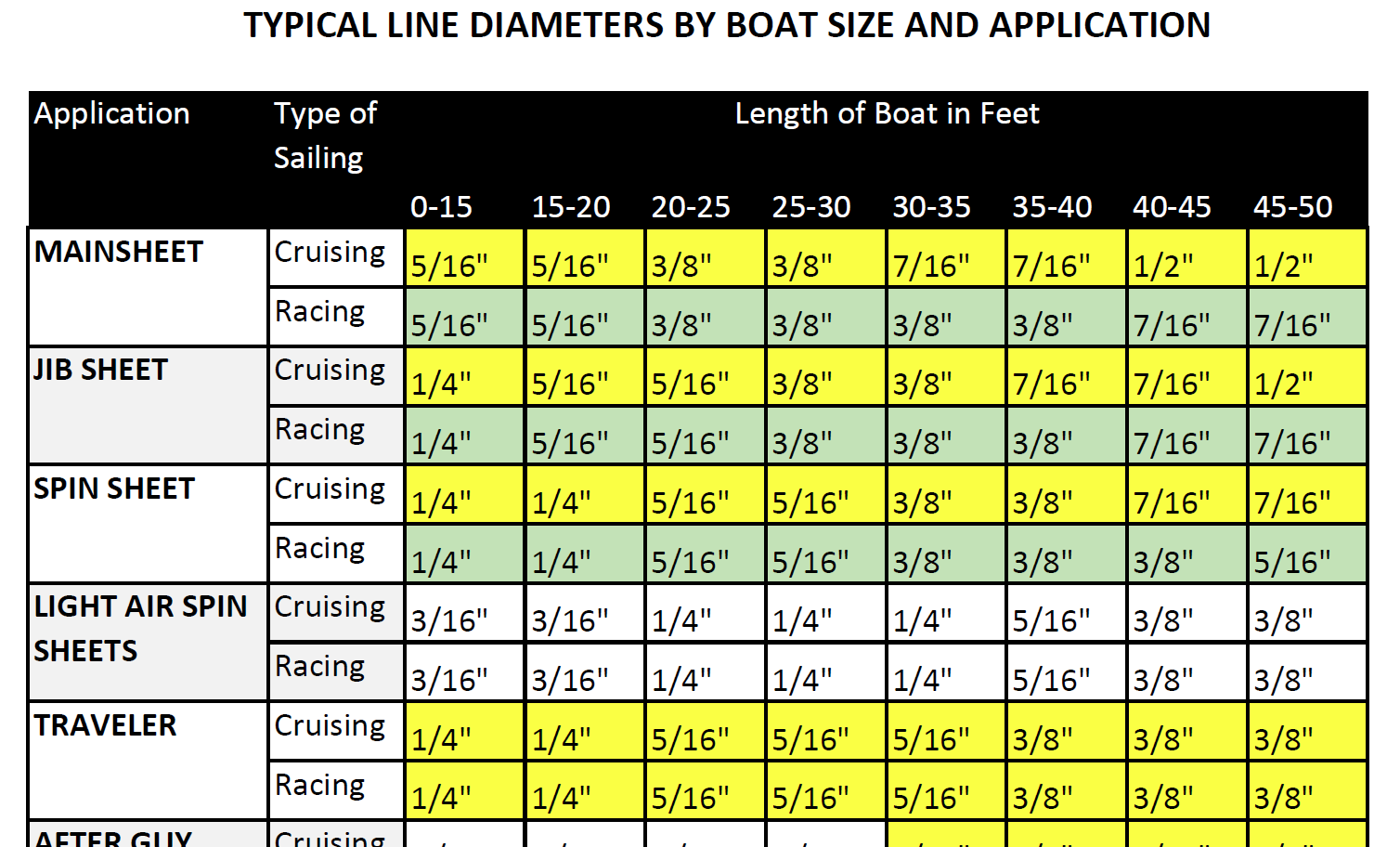

Approximate Line Diameters for Running Rigging

But note the word 'approximate'. More precise diameters can only be determined when additional data regarding line material, sail areas, boat type and safety factors are taken into consideration.

Length of boat

Spinnaker guys

Boom Vang and preventers

Spinnaker sheet

Genoa sheet

Main halyard

Genoa / Jib halyard

Spinnaker halyard

Pole uphaul

Pole downhaul

Reefing pennants

Lengthwise it will of course depend on the layout of the boat, the height of the mast and whether it's a fractional or masthead rig - and if you want to bring everything back to the cockpit...

Read more about Reefing and Sail Handling...

Headsail Roller Reefing Systems Can Jam If Not Set Up Correctly

When headsail roller reefing systems jam there's usually just one reason for it. This is what it is, and here's how to prevent it from happening...

Single Line Reefing; the Simplest Way to Pull a Slab in the Mainsail

Before going to the expense of installing an in-mast or in-boom mainsail roller reefing systems, you should take a look at the simple, dependable and inexpensive single line reefing system

Is Jiffy Reefing the simplest way to reef your boat's mainsail?

Nothing beats the jiffy reefing system for simplicity and reliability. It may have lost some of its popularity due to expensive in mast and in boom reefing systems, but it still works!

Recent Articles

'Natalya', a Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 54DS for Sale

Mar 17, 24 04:07 PM

'Wahoo', a Hunter Passage 42 for Sale

Mar 17, 24 08:13 AM

Used Sailing Equipment For Sale

Feb 28, 24 05:58 AM

Here's where to:

- Find Used Sailboats for Sale...

- Find Used Sailing Gear for Sale...

- List your Sailboat for Sale...

- List your Used Sailing Gear...

Our eBooks...

A few of our Most Popular Pages...

Copyright © 2024 Dick McClary Sailboat-Cruising.com

Running Rigging

Jib Tack, Jib Halyabds, and Jib Sheets.

The jib tack requires to be of great strength, and is made indifferently, accordingly to the judgment of the person who has the fitting out of the yacht, of rope, chain, or flexible wire rope. Rope does very well in vessels under 40 tons, but wire is to be preferred, and it is found to stand better than chain. The jib tack t is fast to the traveller a (Fig. 15), and leads down through a sheave hole * at the bowsprit end (inside the cranse iron) a block is shackled to the end of the tack through which the outhaul is rove. The standing part of the outhaul is put over one of the bitts with a running eye; the hauling part leads on board by the side of the bowsprit. A single rope inhaul is generally fast to the traveller.

The score in the end of the bowsprit has necessarily to be very large, and frequently it is made wider than it need be; at any rate the sheave hole is a source of weakness, and generally if the end of the bowsprit comes off it is close outside the sheave hole, the enormous lateral strain brought on the part by the weather shroud (%) causing the wood to give way. To avoid such accidents as these one or two yachts have the sheave outside the iron, as shown by to. The tack n passes between the ears or "lugs" on the cranse iron at o and p. To o the topmast stay is fitted, and the bobstay block at p. Of course if the score and sheave were put at m, the other score and sheave * would be dispensed with. Generally when the end comes off at the sheave 8 the bowsprit immediately afterwards breaks close off at the stem, unless some one is very smart at letting the jib sheets fly, or in putting the helm down. With the sheave hole at m no such accident would happen.

Jib halyards are, as a rule, made of chain, as it runs better and does not stretch, and the fall stows in a smaller compass when the jib is set; in fact, the fall is generally run through one of the chain pipes

into the forecastle, where it helps a trifle as ballast.* However, several large vessels, such as Livonia, Modwena, and Arrow, have had Manilla rope. The jib halyards are rove through an iron (single) block (which is hooked or shackled to the head cringle of the jib), and then each part leads through an iron (single) block on either side of the masthead (see Fig. 5). The hauling part usually leads down the port side of the mast; the purchase is shackled to the part that leads through the block on the starboard side. In vessels above 40 tons a flexible wire runner is invariably used in addition to the purchase; one end of the runner is shackled to an eye bolt on deck, and the other, after leading through a block on the end of the jib halyard, is shackled to the npper block of the purchase. The purchase consists of a double and single block, or two double; in the former case the single block is below, with the standing part of the tackle fast to it; but where two blocks are used, the standing part of the tackle is made fast to the upper block. As a great deal of "beef" is required to properly set up a jib, it is usual to have a lead of some kind for the " fall" * of the purchase on deck, such as a snatch block. It is, of course, necessary to have a " straight" luff to a jib, but very frequently the purchase is used a little too freely; the result is that the forestay is slacked, and perhaps a link gives way in the halyards; or the luff rope of the jib is stranded (generally near the head or tack, where it has been opened for the splice), and sometimes the bobstay-fall is burst. (We once saw the latter mishap occur on board the Oimara during the match at Southsea.) These mishaps can be generally averted by "easing" the vessel whilst the jib is being set up, choosing the time whilst she is in stays or before the wind, and watching to see that the forestay is not slackened.

Jib sheets in vessels under 80 tons are usually single, but in vessels larger than 80 tons they are double. In the latter case there are two blocks, which are put on the clew cringle; a sheet is rove through each block, and the two parts through the jib sheet holes in the wash strake of the bulwarks; one part of the sheet is then made fast and the other hauled upon.

Fobs Halyards, Fobe Tacks, and Fobb Shebts.

The fore halyards are usually fitted as follows: The standing part is hooked or shackled to an eye bolt under the yoke on the port side, then through a single block hooked to the head of the sail, and up through another single block hung to an eye bolt under the yoke on the starboard side. The downhaul is bent to the head cringle or to the hook of the

* The "fell" of a tackle is the pert that is taken hold of to haul upon.

block. No purchase is necessary, as the sail is set on a stay; but in yachts above 10 tons the luff of the sail is brought taut by a tackle hooked to the tack; the tack leads through the stem head. The tackle oonsists of a single and double block, or two doubles according to the size of the yacht. In yachts of 40 tons and upwards the tack is usually made of flexible wire rope.

Fore sheets in yachts under 15 tons are usually made up of two single blocks. The standing part is made fast to the upper block (hooked and moused or shackled to the clew of the sail). In larger vessels a double, or single, or two double blocks are used, the hauling part or fall always leading from the upper block. In very large vessels, such as 100-ton cutters or yawls, or 140-ton schooners , "runners" are used in addition to tackles. These are called the standing parts of the sheets: one end is hooked on the tackle by an eye; the other end is passed through a bullseye of lignum vitss on the clew of the sail, and is then belayed to a cavel. The sail is then Bheeted home with the tackle.

Main and Peak Halyards, Main Tack, Main Sheet, and Main

The main or throat halyards are generally rove through a treble block at the masthead, and a double block on the jaws of the gaff. The hauling part of the main halyards leads down the starboard side of the mast, and is belayed to the mast bitts. The main purchase is fast to the standing part, and usually consists of a oouple of double blocks, and the lower one is generally hooked to an eye bolt in the deck on the starboard side. In vessels under 15 tons it is unusual to have a main purchase, and when there is no purchase the upper main halyard block is a double one, and the lower a single. However, racing 10-tonners have a main purchase, and many 5-tonners have one. The principal object in having a main purchase in a small craft is that the mainsail can be set better, as in starting with "all canvas down" the last two or three pulls become very heavy, especially if the hands on the peak have been a little too quick; and a much tauter luff can be got by the purchasfl^than by the main tack tackle. Of course the latter is dispensed with in small vessels where the purchase is used, and the tack made fast by a lacing round the goose-neck of the boom. By doing away with the tack tackle at least 6in. greater length of luff can be had in a 5-tonner, and this may be of some advantage. The sail cannot be triced up, of course, without casting off the main tack lacing; but some yacht sailers oonsider this an advantage, as no doubt sailing a vessel in a strong wind with the main tack triced up very badly stretches the sail, looks very ugly.

The peak halyards in almost all vessels under 140 tons are rove through two single blocks on the gaff and three on the masthead, as shown in Plate I. and Fig. 5. Some vessels above 140 tons have three blocks on the gaff, and in such cases the middle block on the masthead is usually a double one. The standing part of the peak halyards to which the purchase is fast leads through the upper block and down on the port side.

The usual practice in racing vessels is to have a wire leather-covered span (copper wire is best) with an iron-bound bullseye for each block on the gaff to work upon, and this plan no doubt causes a more equal distribution of the strain on the gaff. The binding of the bullseye

has an eye to take the hook of the block. In Fig. 16 a is a portion of the gaff, b is the span; c c are the eyes of the span and thumb cleats on the gaff to prevent the eyes slipping, d is the bullseye with one of the peak halyard blocks hooked to it.

The main tack generally is a gun tackle purchase, but in vessels above 60 tons a double and single or two double blocks are used. In addition, some large cutters have a runner rove through the tack cringle, one end being fast to the goose-neck of the boom, and the other to the tackle. In laced mainsails the tack is secured by a lacing to the goose-neck.

The main boom is usually fitted to the spider hoop round the mast by a universal joint usually termed the main boom goose-neck.

The main sheet should be made of left-handed, slack-laid, six-stranded Manilla rope. The blocks required are a three-fold on the boom, a two-fold on the buffer or hone, as the case may be, and a single block on each quarter for the lead. Yachts of less than 15 tons have a double block on the boom, and single on the buffer.

Many American yachts have a horse in length about one-third the width of the counter for the mainsheet block to travel on. For small vessels, at any rate, this plan is a good one, as the boom can be kept down so much better on a wind, as less sheet will be out than there would be without the horse. A stout ring of indiarubber should be on either end of the horse, to relieve the shock as the boom goes over.

The mainsail outhaul is made np of a horse on the boom, a shackle as traveller, a wire or chain runner outhaul (attached to the shackle, and rove through a sheave hole at the boom end), and a tackle. (See Fig. 17.) In small vessels the latter consists of one block only; in large vessels of two single, or a double and single, or two double blocks.

The old-fashioned plan of outhaul, and one still very much in use, consists of an iron traveller (a large leather-covered ring) on the boom end, a chain or rope through a sheave hole and a tackle. This latter plan is perhaps the stronger of the two; but an objection to it is that the traveller very frequently gets jammed and the reef cleats have to be farther forward than desirable, to allow the traveller to work.

Sometimes, instead of a sheave hole, the sheave for the outhaul is fitted right at the extreme end of the boom, on to which an iron cap is fitted for the purpose.

Topsail Halyards, Sheets, and Tacks.

The topsail halyards in vessels under 10 tons consist of a single rope rove through a sheave hole under the eyes of the topmast rigging.

Yachts of 10 tons and over have a block which hooks to a strop or sling on the yard, or if the topsail be a jib-headed one, to the head cringle. The standing part of the halyard has a running eye, which is put over the topmast, and rests on the eyes of the rigging; the halyard is rove through the block (which has to be hooked to the yard), and through the sheave hole at the topmast head. It is best to have a couple of thumb cleats on the yard where it has to be slung; there is then no danger of the strop slipping, or of the yard being wrongly slung.

When the topsail yard is of great length, as in most yachts of 40 tons and upwards, an upper halyard is provided (called also sometimes a tripping line or trip halyard, becausfe the rope is of use in tripping the yard in hoisting or lowering). This is simply a single rope bent to the upper part of the yard, and rove through a sheave hole in the pole, above the eyes of the topmast rigging. The upper halyards are mainly useful in hoisting and for lowering to get the yard peaked; however, for very long yards, if bent sufficiently near the upper end, they may in a small degree help to keep the peak of the sail from* sagging to leeward, or prevent the yard bending.

The topsail sheet is always a single * Manilla rope, as tarred hemp rope would stain the mainsail in wet weather. It leads through a cheek block on the gaff end, then through a block shackled to an eye bolt under the jaws of the gaff; but in most racing vessels nowadays a pendant or whip is used for this block, as shown in Plate I. The pendant should go round the mast with a running eye. By this arrangement the strain is taken off the jaws of the gaff and consequently off the main halyards. A common plan of fitting this block and whip is shown in Pig. 18. The hauling part of the sheet is generally put round one of the winches on the mast to " sheet home " the topsail.

The topsail tack is usually a strong piece of Manilla with a thimble spliced in it, to which the tack tackle is hooked.

Jib-topsail halyards and main-topmast-staysail halyards are usually single ropes rove through a tail block on topmast head; but one or two large vessels have a lower block, with a spring hook, which is hooked to the head of the sail. In such cases, the standing part of the halyards is fitted on the topmast head with a running eye or bight.

• The Oimara, cutter, had doable topsail sheets rove in this way : one end of the sheet was made fast to the gaff end; the other end of the sheet was rove through a single block on the clew of the sail; then through the oheek block at the end of the gaff, through a block at the jaws of the gaff, and round the winch.

Spinnaerb Halyards, Outhaul, &c.

Spinnaker halyards are invariably single, and rove through a tail block at the topmast bead.

The spinnaker boom is usually fitted with a movable goose-neck at its inner end. The goose-neck consists of a universal joint and round-neck pin, and sockets. (Square iron was formerly used for the neck, but there was always a difficulty in getting the neck shipped in the boom, and round iron was consequently introduced.) The pin is generally put into its socket on the mast, and then the boom end is brought to the neck.

At the outer end of the boom are a couple of good-sized thumb cleats, against which the running eye of the after and fore guy are put. The fore guy (when one is used) is a single rope; the after guy has a pendant or whip with a block at the end, through which a rope is rove. The standing part of this rope is made fast to a cavel-pin on the quarter, and so is the hauling part when belayed. The after guy thus forms a single whip-purchase (see Plate I.). The outhaul is rove through a tail block* at the outer end of the spinnaker boom, and sometimes a snatch block is provided for a lead at the inner end on th§ mast. The topping lift consists of two single, a double and single, or two double blocks, according to the size of the yacht.

The upper block of the topping lift is a rope strop tail block, with a running eye to go round the masthead. The lower block is iron bound, and hooks to an eye strop on the boom.

Formerly a bobstay was used ; but, if the boom is not allowed to lift, it will bend like a bow; in fact, the bobstay was found to be a fruitful cause of a boom breaking, if there was any wind at all, and so bobstays were discarded. The danger of a boom breaking through its buckling up can be greatly lessened by having one hand to attend to the topping lift; as the boom rears and bends haul on the lift, and the bend will practically be "lifted" out.

Small yachts seldom have a fore guy to spinnaker boom, but bend a rope to the tack of the sail (just as the outhaul is bent) leading to the bowsprit end; this rope serves as a fore guy, or brace, to haul the boom forward; and when the spinnaker requires to be shifted to the bowsprit, the boom outhaul is slackened up and the tack hauled out to bowsprit end. Thus double outhauls are bent to the spinnaker tack cringle, and one

• Formerly a hole vu out in the boom end, and a sheaye fitted for the outhaul to run through; this plan is now abandoned, as, unless the boom happens to oome with one partionlar side uppermost, an unfair lead may result rove through the sheave hole or block at the spinnaker boom end, and the other through a block at bowsprit end. But generally the large spinnaker (set as such) has too much hoist for the jib spinnaker, and a shift has to be made for the bowsprit spinnaker, which is hoisted by the jib topsail halyards if that sail be not already set; even in such case no fore guy is used in small vessels, but to ease the boom forward one hand slackens up the topping lift a little, and another the after guy, and, if there be any wind at all, the boom will readily go forward. In a five-tonner the after guy is a single rope without purchase, and the topping lift is also a single rope, rove through a block under the lower cap.

A schooner has a main and fore spinnaker fitted in the manner just described, and the usual bowsprit spinnaker as well, which is usually hoisted by the jib topsail halyards.

As spinnaker booms are now carried so very long, they will not go under the forestay; consequently, when the spinnaker has to be shifted, the boom must be unshipped. To shift the boom, the usual practice is to top it up, lift it away from the goose-neck, and then launch the inner end aft till the outer end will clear the forestay, or leech of foresail if that sail be set. If the boom is not over long, the inner end can be lowered down the fore hatch or over the side of the vessel until the other end will clear the forestay (see als<J page 79).

When spinnakers were first introduced no goose-neck was used, the heel of the boom being lashed against the mast. A practice then sometimes was to have a sheave hole at either end of the boom, with a rope three times the length of the boom rove through each sheave hole. One end of this rope served as the outhaul, the other for the lashing round the mast. To shift over, the boom was launched across to the other rail, and what had been the inboard end became the outboard end. Of course the guys had to be shifted from one end to the other. As spinnaker booms are now of such enormous length, it would be almost impossible, and highly dangerous, to work them in this way, although it might do for a five-tonner.

Spinnaker booms when first fitted with the goose-neck were no longer than the length from deck to hounds, so that they could be worked under the forestay without being unshipped. However, it would appear that the advantages of a longer boom are greater than the inconvenience of having to. unship it for shifting, and now, generally, a spinnaker boom when shifted and topped up and down the mast, reaches above the upper cap.

The following plan was worked during the summer of 1876 in the Lily, 10-tonner, but we have never met with it elsewhere. The arrangement was thus described: Take a yacht of say 65 tons, and suppose her 70ft. long and 15ft. beam, with a mast measuring 60ft. from deck to cap, from which if 9ft. is subtracted for masthead, and 4ft. more allowed for the angle made by the forestay, a spinnaker boom, to swing over clear, cannot exceed 43ft. (as the goose-neck is 3ft. from deck), which of course is much too little to balance the mainboom and sail. It is proposed to have a boom of 42ft., and another smaller one of 21ft. made a little heavier than the long one, and fitted with two irons 7ft. apart; the longer one to be made in the usual manner, with bolts in both ends, for the goose-neck; but the sheaves in the ends to be, one vertical, and the other horizontal. It will then make a very snug storm boom for the balloon jib when shipped singly, whilst the smaller one, by leading a tack rope (or outhaul) through the block on the outer iron will do very well for the staysail. See Fig. 19: in case No. 1, the boom is on end and ready for letting fall to starboard; and in Ho. 2 dipped and falling to port. A A (No. 1) represents the 42ft. boom, and B B the 21-footer; the dotted line b b the arc the boom would travel if not let run down; and the dotted line c c the actual line it travels when housed. C in the small diagram represents the outer iron or cap on the end of the small

boom (which can be made square or round; in the diagram it is made square, to prevent twisting), and a a bolt to which the standing part of the heel rope is made fast by clip hooks; the rope passes through the horizontal sheave at h, and back to the block on the cap at/. The fall can be belayed to a cleat on the small boom, or would greatly ease the strain on the gooseneck if made fast on the rail or to the rigging. When gybing it would only be necessary to top the boom by the lift, let go the heel rope, and let it run down; then swing over, lower away, and haul out the boom when squared. It would be better to hook on the Burton purchase to the cap at e, both as an extra support and to make sure of the boom whilst swinging. This plan would not only obviate the danger and trouble of dipping the boom, but give a 57ft. spar, besides giving greater strength, the boom being double where the most strain comes; and the extra weight is a positive advantage, as helping to balance the main boom. Of course this plan would allow of almost any length of spars, as a 40ft. lower boom would give a 74ft. spar, and still leave 8ft. between the irons; and in these days of excessive spars and canvas no doubt it would be attempted to balance a ringtail, but the lengths given seem a good comparative length for any class.

A more simple plan for " telescoping " a spinnaker boom is shown by

Fig. 20, a is the inner part of the boom; c is a brass cylinder with an

angular slot in it at 8. This cylinder is fixed tightly to the outer part of the boom by the screw bolts i i. The two parts of the boom meet inside the cylinder at the ticked line t. When the two parts "of the boom are to be used together, the ring m is put on the cylinder. The inboard part of the boom is then put into the cylinder, and the whole is firmly screwed up by the thumb-screw x. Both parts of the boom have their ends " socketed " so as to take a goose-neck, and thus either part can be used alone.

Was this article helpful?

Recommended Programs

Myboatplans 518 Boat Plans

Boat Alert Hull ID History Search

3D Boat Design Software Package

Related Posts

- Standing Rigging - Boat Sailing Guide

- Plan Drawing Fregatt - Rigging

- How Are Catamaran Masts Fixed Down

- Rigging a singlehanded dinghy

- Rigging a twohanded dinghy

- Rig Construction - Ship Design

Readers' Questions

What is yacht running rigging?

Yacht running rigging is the ropes and cables used to control the movement of the sails and spars of a sailing yacht. It generally consists of halyards, sheets, guys, and sometimes vangs, used to raise, lower, and angle the sails.

Nautical Terminology 101 – Running Rigging

October 5th, 2023 by team

by B.J. Porter (Contributing Editor)

Last month we talked about standing rigging – the fixed, permanent parts of your boat. This month, we’re on to running rigging – the various lines that you move, pull, and release to sail the boat. Running rigging has at least one free end. For this article, we’re talking about the rigging on a modern sloop, a comparatively simple rig compared to many older rig styles.

The astute observer will note I used the word “lines,” not “ropes.” With only a few exceptions, there are no “ropes” on a sailboat. There are many things made of rope on a sailboat, but the proper names for them once they have a job do not include the word “rope.” Sailors talk mostly about lines, sheets, halyards, and so on.

(Ten bonus points for anyone who can name some of the only “ropes” on a boat in the comments. Hint: We find at least one on sails without hanks or cars.)

A sheet is a line which controls a sail. It’s used to trim the sail (tighten it in) or ease it (loosen and let it out). The name for the sheet is {sailname} + “sheet.” Sheets always attach to the clew of the sail.

Main sheet – Controls trim on the mainsail. Usually run through a series of blocks to get purchase for easier trimming.

Jib/genoa sheet – Handles the first, largest headsail. They will turn around blocks and run through a car to change sheeting angles , but there isn’t a purchase involved. Instead, headsail sheets run to the primary (largest) cockpit winches. Like the sail name itself, the use of jib and Genoa is often interchangeable and informal. So you may well be flying a giant overlapping Genoa from the headstay while people in the cockpit are telling you to work all the knots and kinks out of the “jib sheet.”

Staysail sheet – if there is a staysail, this runs through its own adjustable deck car back to the cockpit.

Spinnaker sheet – trims the spinnaker, and attaches to the leeward side of the sail (remember windward/leeward from August?).

Headsail and spinnaker sheets are usually paired and run to each side of the boat for use on different tacks and gybes. One line is taught with the sail load, and the other one is the “lazy” sheet, because it isn’t doing anything.

Halyards haul sails up to the top of their set position and hold them there. They attach to the head of the sail, run through a sheave at the top or middle of the mast, and back down to deck level. Some halyards are external (outside the mast) but many run inside the mast and only appear through slots near deck level.

Many halyards have a rope clutch on them to hold the rope. But rope clutches can slip a little with high loads, so most also have a cleat or self-tailing winch to ensure there is no slipping once the sail loads up.

Halyards are made from very low stretch lines, and race boats often strip the outer cover off the halyards to save weight.

Primary halyards are the main halyard , jib/genoa halyard , staysail halyard , and spinnaker halyard .

Many boats have one or more spare halyards, in case one breaks or the crew needs to go up the rig while other halyards are in use. Halyards may end at the mast, or run back to the cockpit.

Control lines

Other lines are used to control the sails, trim the rig, and operate the boat. We’ll group them by functional groups, so you can explore and identify them easily the next time you’re on a boat.

IMPORTANT NOTE: Not all boats have all the controls and lines listed.

Mainsail lines

- Outhaul , or clew outhaul – line to the clew of the mainsail that adjusts foot tension and the fullness of the main.

- Cunningham – adjusts the luff tension. It’s usually a line through a grommet near the tack of the sail a little way up the luff.

- Reef lines – used to reef (shorten) the sail, these run through grommets (or cringles ) near the luff the sail at fixed reef points.

- Vang – or “Boom vang” runs from the bottom of the boom to the deck and keeps the boom height constant. This may be a block and tackle with lines, or a hydraulic or mechanical cylinder on larger boats.

- Traveler – controls the angle of attack of the mainsail. The mainsheet runs through a block on the traveler, but the traveler itself is an adjustable car usually moved with a line run between blocks for purchase.

- Topping lift – supports the boom from the masthead when the boat is at rest. The topping usually runs to the masthead. Some owners use an old halyard for the topper, so it can act as a spare halyard.

- Leech lines and foot lines – small lines along the edges of the sail to set the tension or curve in the sail edge.

Headsail lines

- Leech lines and foot lines – identical in function on head sails and the mainsail, but headsails don’t have foot lines as often.

- Furling line – manual sail furlers often use a line to turn the furling drum which wraps onto the drum when the sail is out.

- Barber hauler – a temporary replacement sheet run through a separate block to get better sheeting angles sailing off the wind.

Spinnaker and pole lines

Symmetrical spinnakers need more lines than asymmetrical sails, because they use a pole to support the sail and keep it open. The pole must be trimmed to keep the angle of attack correct.

- Spinnaker guy – or “brace” for our friends on the other side of the pond, is the line attached to the windward side of a symmetrical spinnaker. it runs through the spinnaker pole jaws. NOTE: Some boats, usually smaller ones, do not run a separate sheet and guy on each side of the boat. One line runs to each corner of the sail, and is called the sheet when it’s used to trim the sail, and the guy when it trims the pole.

- Tack line – on asymmetrical spinnakers, a tack line runs from the sail tack to a deck fitting or pole. It’s usually adjustable for wind conditions.

- Twing – light line usually with a block to adjust the angle of the spinnaker sheet. Often left off, especially in light air racing.

- Pole downhaul – runs from the bottom of the spinnaker pole to a deck fitting, used to keep the spinnaker pole level and prevent it from “skying” or flying up on the end.

- Pole topping lift – pulls the pole up and level.

Names and Variations

As I hinted with the spinnaker guy/brace name differences between North America and the U.K., there are some different names which may be used based on where you’re sailing. But you may hear a vang called a “kicker” or other terms used that aren’t here for the same things anywhere.

For sure we’ve missed a few things, and I’d love to hear some of your local variations in the comments!

- Posted in Blog , Boat Care , Boating Tips , Cruising , Fishing , iNavX , iNavX: How To , News , Sailing , Sailing Tips

- No Comments

- Tags: halyards , line , mainsail , rigging , sheets , spinnaker

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Send us a message

- AROUND THE SAILING WORLD

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Email Newsletters

- Best Marine Electronics & Technology

- America’s Cup

- St. Petersburg

- Caribbean Championship

- Boating Safety

Simple Ways to Optimize Running Rigging

- By Erik Shampain

- December 6, 2022

It’s easy to underestimate the benefits of good running rigging. There are many rope products on the market, and there is a time and a place for most of them. Let’s take a look at lines that need the most attention and why, as well as basic rules for using low-stretch line, using lightweight or tapered line where most beneficial and using rope that is easy to work with.

Let’s start up front with the headsail halyard. Luff tension greatly affects shape and thus performance of the jib or genoa, so having a halyard that is as low-stretch as possible is paramount. Saving a little weight aloft is also key, so find a lightweight rope as well. It’s a little against the norm, but for club racing boats that aren’t tapering their halyards, I really like some of the Vectran-cored ropes. Products like Samson’s Validator and New England Ropes V-100 are easy on the hands and easy to splice. For a little more grand-prixed tapered halyard, talk to our local rigger about using a DUX core, or other heat-set Dyneema, with a Technora-based cover. Lately, I’ve been using a lot of Marlow’s D12 MAX 78 and 99. Tapering the halyard saves weight aloft as well. I like soft shackles for jib halyards. There, weight savings aloft generally outweighs the little extra time a bowman needs to attach the sail. This is especially true in sprit boats where the jib is rarely removed from the headstay.

Pro Tip: When not racing, use a halyard leader to pull the halyards to the top of the mast, getting the tapered section out of the sun. For extra protection, put all the halyard tails into an old duffle bag at the base of the mast when not in use.

For jib sheets, I follow the same low-stretch rule as the jib halyard. I don’t want the jib sheet to stretch at all when a puff hits. On boats with overlapping genoas, I don’t generally recommend tapering the line because by the time the genoa is trimmed all the way in, the clew is really close to the block. On boats with non-overlapping jibs, tapering is an easy way to save a little weigh. Plus, the smaller core size runs through across the boat more easily in tacks. I’ve been using soft shackles on the jib or genoa sheets for a while now, mostly because they don’t beat the mast up during tacks. There also a bit “softer” when they hit you.

What about jib lead adjusters? There are a couple of approaches here. Some believe a little stretch is okay, as it allows the lead to rock aft a couple of millimeters in puffs, which twists the top of the jib off slightly. This can be fast as it helps the boat transition through puffs and lulls. I am a fan of this as long as it isn’t too stretchy. I use low-stretch Dyneema for the gross part of the purchase and then a friendlier-on-the-hands rope for the fine tune side, the part that is being handled. Samson Warpspeed or New England Enduro Braid work well.

Spinnaker sheets are a fun one. They should be relatively low-stretch but not necessarily the lowest stretch. I’ve found that near-zero stretch lines can wreak havoc on people and hardware when flogging or when the chute is collapsing. They have to be easy on the hands, as they are the most moved sheets on the boat, and they should be tapered as far as you can get away with. Tapering saves weigh, which is very important in keeping the spinnaker clew lifting up, especially in light air when sails want to droop. Again, Samson Warpseed and New England Enduro braid are good. For boats with grinders or even small boats with no winches, a cover that is a little grippier or stronger is good. Most Technora-based covers work well for this purpose.

Pro Tip No. 2: On boats with asymmetric spinnakers I like to connect the ‘Y’ sheet with a soft shackle that also goes to the spinnaker. This saves weight. I sew a Velcro strip around one part of the shackle (see picture) so that the soft shackle stays with the ‘Y’ sheet when open. This is beneficial when you have to quickly disconnect or re-run a sheet, replace one sheet, or even quickly replace a soft shackle. On most boats I will keep one spare spinnaker sheet with soft shackle down below as a spare side, changing sheet, or code zero sheet. On boats with a symmetric spinnaker, we’ll splice the spinnaker sheet to the afterguy shackle to save weight in the clew.

The spinnaker halyard has a couple of more options. For halyards supporting code zeros, zero stretch is important. The same principals we used when talking about the jib halyard apply here. For boats without code zeros, I like a little softer halyard with a touch of give. Those tend to run though sheaves better without kinking. Enduro and Warpseed are good for these applications. Most bowmen prefer a shackle that is quick and easy to open. Since a happy bowman is a good thing, I will generally use an appropriately sized Tylaska shackle or dogbone style shackle for those halyards

For symmetric spinnaker boats, the afterguy must be very low stretch line. I go back to products like covered Vectran for club-level sheets. I also find that afterguys generally last longer if I don’t taper them. When the pole is squared back, the afterguys often run pretty hard across the lifelines, producing a fair amount of chafe. Covered lines help minimize that.

For tack lines on asymmetric boats, I like matching spinnaker halyard material on club-level boats and using low-stretch heat-set Dyneema cores with a chafe resistant cover for grand prix and sportboats.

Like the headsail halyard, a near-zero stretch main halyard is also important. For me the same line applications apply. Keep the mainsail head at full hoist at all costs. I will often match the material I use for main and jib halyards.

It is most important that the main sheet sit in the winch jaws well and tail perfectly. This is a strict combination of sizing and pliability. I’ve found that the New England Ropes Enduro braid and the Samson Warpspeed II work well for club-level boats with and without winches. For a slightly longer lasting product with some chafe resistance, try any manufacturer’s Technora-based covered line.

The most under-appreciated and least thought about rope on a boat always seems to be the outhaul. The last thing you want when the wind comes up is for your mainsail to get fuller. Spend some time here and use very low-stretch rope. Most heat-set Dyneemas will work great for the gross tune side of the purchase.

Pro Tip No. 3: Minimizing the last purchase of an outhaul greatly increases the ease with which it can be pulled on or eased out. For example, you could have a 6-to-1 to one pulling a 2-to-1, pulling a 2-to-1 and then to the sail for a 24-to-1. Or, better yet, you could have a 4-to-1 pulling a 3-to-1, pulling a 2-to-1 for a 24-to-1 as well. The latter example will work better. Trust me. I’m a doctor . . . sort of. We built an outhaul like this on a SC50. I can pull it on upwind in heavy air with little problem. On the flip side, in light air downwind, it eases just as well. In fact, if memory serves me right, we did a 3-to-1 in the end rather than the 4-to-1 for a total of 18-to-1 and it worked well.

Runners and backstays should have extremely low stretch. A pumping mast and sagging forestay in breeze isn’t fast. Runner tails, like the mainsheet, should perfectly fit the winch and tail easily without kinking.

With so many options readily on the market now, it can be very confusing. I always recommend contacting your local rigger if you have any questions at all about what rope is right for you. They’ll get you pulling in the right direction.

- More: cordage , running rigging , sailboat gear

Wingfoiling Gear: A Beginner’s Guide

Suiting Up with Gill’s ZenTherm 2.0

Gill Verso Lite Smock Keeps it Simple

A Better Electronic Compass

Brauer Sails into Hearts, Minds and History

Anticipation and Temptation

America’s Offshore Couple

Jobson All-Star Juniors 2024: The Fast Generation

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

Guide to Understanding Sail Rig Types (with Pictures)

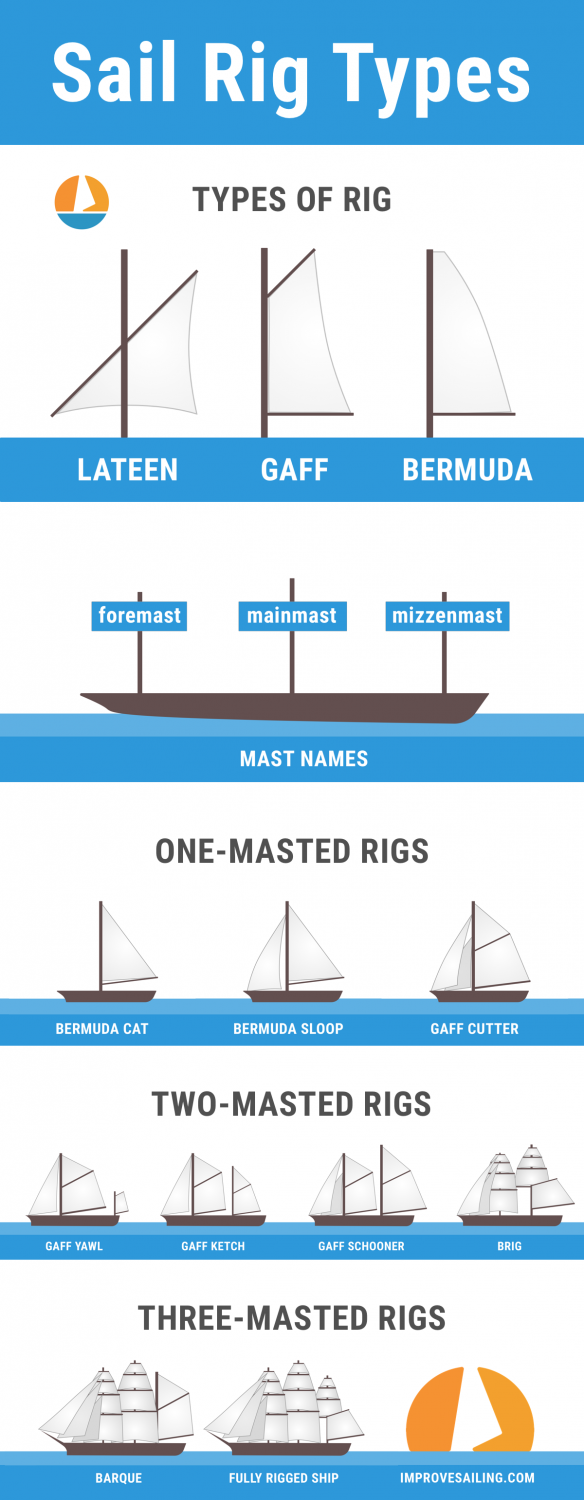

There are a lot of different sail rig types and it can be difficult to remember what's what. So I've come up with a system. Let me explain it in this article.

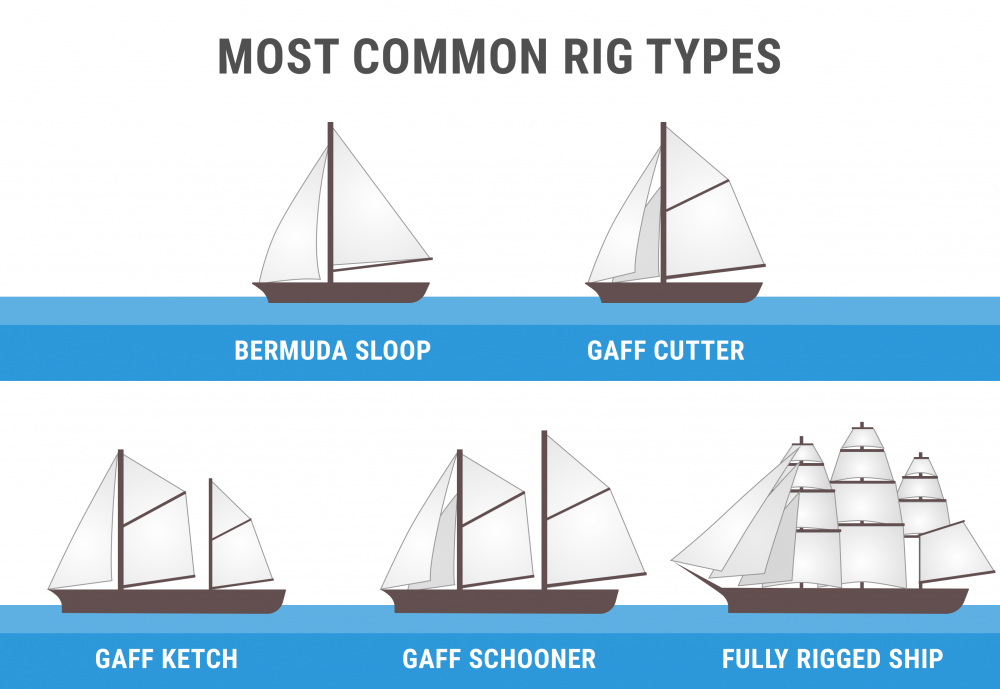

What are the different types of sail rig? The sail rig is determined by the number of masts and the layout and shape of sails. Most modern ships are fore-and-aft rigged, while old ships are square-rigged. Rigs with one mast are sloops and cutters. Ketches, yawls, brigs, and schooners have two masts. Barques have three masts. Rigs can contain up to seven masts.

'Yeah, that's a gaff brig, and that a Bermuda cutter' - If you don't know what this means (neither did I) and want to know what to call a two-masted ship with a square-rigged mainsail, this article is definitely for you.

On this page:

More info on sail rig types, mast configurations and rig types, rigs with one mast, rigs with two masts, rigs with three masts, related questions.

This article is part 2 of my series on sails and rig types. Part 1 is all about the different types of sails. If you want to know everything there is to know about sails once and for all, I really recommend you read it. It gives a good overview of sail types and is easy to understand.

The Ultimate Guide to Sail Types and Rigs (with Pictures)

First of all, what is a sail rig? A sail rig is the way in which the sails are attached to the mast(s). In other words, it's the setup or configuration of the sailboat. The rig consists of the sail and mast hardware. The sail rig and sail type are both part of the sail plan. We usually use the sail rig type to refer to the type of boat.

Let's start by taking a look at the most commonly used modern sail rigs. Don't worry if you don't exactly understand what's going on. At the end of this article, you'll understand everything about rig types.

The sail rig and sail plan are often used interchangeably. When we talk of the sail rig we usually mean the sail plan . Although they are not quite the same. A sail plan is the set of drawings by the naval architect that shows the different combinations of sails and how they are set up for different weather conditions. For example a light air sail plan, storm sail plan, and the working sail plan (which is used most of the time).

So let's take a look at the three things that make up the sail plan.

The 3 things that make up the sail plan

I want to do a quick recap of my previous article. A sail plan is made up of:

- Mast configuration - refers to the number of masts and where they are placed

- Sail type - refers to the sail shape and functionality

- Rig type - refers to the way these sails are set up on your boat

I'll explore the most common rig types in detail later in this post. I've also added pictures to learn to recognize them more easily. ( Click here to skip to the section with pictures ).

How to recognize the sail plan?

So how do you know what kind of boat you're dealing with? If you want to determine what the rig type of a boat is, you need to look at these three things:

- Check the number of masts, and how they are set up.

- You look at the type of sails used (the shape of the sails, how many there are, and what functionality they have).

- And you have to determine the rig type, which means the way the sails are set up.

Below I'll explain each of these factors in more detail.

The most common rig types on sailboats

To give you an idea of the most-used sail rigs, I'll quickly summarize some sail plans below and mention the three things that make up their sail plan.

- Bermuda sloop - one mast, one mainsail, one headsail, fore-and-aft rigged

- Gaff cutter - one mast, one mainsail, two staysails, fore-and-aft rigged

- Gaff schooner - two-masted (foremast), two mainsails, staysails, fore-and-aft rigged

- Gaff ketch - two-masted (mizzen), two mainsails, staysails, fore-and-aft rigged

- Full-rigged ship or tall ship - three or more masts, mainsail on each mast, staysails, square-rigged

The first word is the shape and rigging of the mainsail. So this is the way the sail is attached to the mast. I'll go into this later on. The second word refers to the mast setup and amount of sails used.

Most sailboats are Bermuda sloops. Gaff-rigged sails are mostly found on older, classic boats. Square-rigged sails are generally not used anymore.

But first I want to discuss the three factors that make up the sail plan in more detail.

Ways to rig sails

There are basically two ways to rig sails:

- From side to side, called Square-rigged sails - the classic pirate sails

- From front to back, called Fore-and-aft rigged sails - the modern sail rig

Almost all boats are fore-and-aft rigged nowadays.

Square sails are good for running downwind, but they're pretty useless when you're on an upwind tack. These sails were used on Viking longships, for example. Their boats were quicker downwind than the boats with fore-and-aft rigged sails, but they didn't handle as well.

The Arabs first used fore-and-aft rigged sails, making them quicker in difficult wind conditions.

Quick recap from part 1: the reason most boats are fore-and-aft rigged today is the increased maneuverability of this configuration. A square-rigged ship is only good for downwind runs, but a fore-and-aft rigged ship can sail close to the wind, using the lift to move forward.

The way the sails are attached to the mast determines the shape of the sail. The square-rigged sails are always attached the same way to the mast. The fore-and-aft rig, however, has a lot of variations.

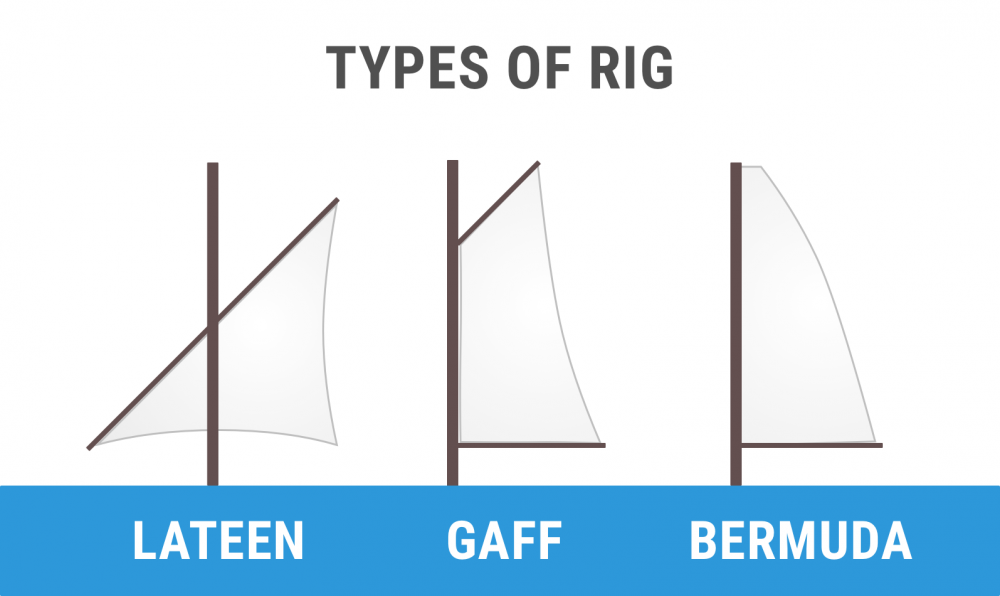

The three main sail rigs are:

- Bermuda rig - most used - has a three-sided (triangular) mainsail

- Gaff rig - has a four-sided mainsail, the head of the mainsail is guided by a gaff

- Lateen rig - has a three-sided (triangular) mainsail on a long yard

The Bermuda is the most used, the gaff is a bit old-fashioned, and the lateen rig is outdated (about a thousand years). Lateen rigs were used by the Moors. The Bermuda rig is actually based on the Lateen rig (the Dutch got inspired by the Moors).

Other rig types that are not very common anymore are:

- Junk rig - has horizontal battens to control the sail

- Settee rig - Lateen with the front corner cut off

- Crabclaw rig

Mast configuration

Okay, we know the shape of the mainsail. Now it's time to take a look at the mast configuration. The first thing is the number of masts:

- one-masted boats

- two-masted boats

- three-masted boats

- four masts or up

- full or ship-rigged boats - also called 'ships' or 'tall ships'

I've briefly mentioned the one and two mast configurations in part 1 of this article. In this part, I'll also go over the three-masted configurations, and the tall ships as well.

A boat with one mast has a straightforward configuration because there's just one mast. You can choose to carry more sails or less, but that's about it.

A boat with two masts or more gets interesting. When you add a mast, it means you have to decide where to put the extra mast: in front, or in back of the mainmast. You can also choose whether or not the extra mast will carry an extra mainsail. The placement and size of the extra mast are important in determining what kind of boat we're dealing with. So you start by locating the largest mast, which is always the mainmast.

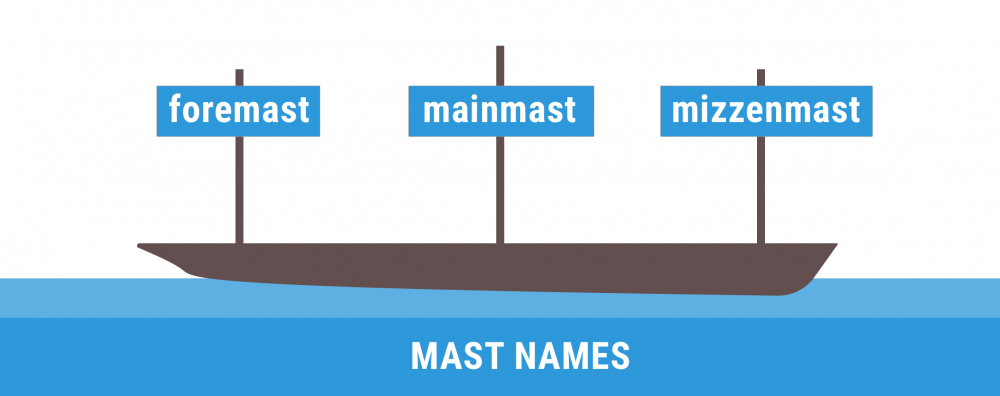

From front to back: the first mast is called the foremast. The middle mast is called the mainmast. And the rear mast is called the mizzenmast.

What is the mizzenmast? The mizzenmast is the aft-most (rear) mast on a sailboat with three or more masts or the mast behind the mainmast on a boat with two masts. The mizzenmast carries the mizzen sail. On a two-masted boat, the mizzenmast is always (slightly) smaller than the mainmast. What is the purpose of the mizzen sail? The mizzen sail provides more sail area and flexibility in sail plan. It can be used as a big wind rudder, helping the sailor to have more control over the stern of the ship. It pushes the stern away from the wind and forces the bow in the opposite way. This may help to bring the bow into the wind when at anchor.

I always look at the number of masts first, because this is the easiest to spot. So to make this stuff more easy to understand, I've divided up the rig types based on the number of masts below.

Why would you want more masts and sail anyways?

Good question. The biggest advantage of two masts compared to one (let's say a ketch compared to a sloop), is that it allows you to use multiple smaller sails to get the same sail area. It also allows for shorter masts.

This means you reduce the stress on the rigging and the masts, which makes the ketch rig safer and less prone to wear and tear. It also doesn't capsize as quickly. So there are a couple of real advantages of a ketch rig over a sloop rig.

In the case of one mast, we look at the number of sails it carries.

Boats with one mast can have either one sail, two sails, or three or more sails.

Most single-masted boats are sloops, which means one mast with two sails (mainsail + headsail). The extra sail increases maneuverability. The mainsail gives you control over the stern, while the headsail gives you control over the bow.

Sailor tip: you steer a boat using its sails, not using its rudder.

The one-masted rigs are:

- Cat - one mast, one sail

- Sloop - one mast, two sails

- Cutter - one mast, three or more sails

The cat is the simplest sail plan and has one mast with one sail. It's easy to handle alone, so it's very popular as a fishing boat. Most (very) small sailboats are catboats, like the Sunfish, and many Laser varieties. But it has a limited sail area and doesn't give you the control and options you have with more sails.

The most common sail plan is the sloop. It has one mast and two sails: the main and headsail. Most sloops have a Bermuda mainsail. It's one of the best racing rigs because it's able to sail very close to the wind (also called 'weatherly'). It's one of the fastest rig types for upwind sailing.

It's a simple sail plan that allows for high performance, and you can sail it short-handed. That's why most sailboats you see today are (Bermuda) sloops.

This rig is also called the Marconi rig, and it was developed by a Dutch Bermudian (or a Bermudian Dutchman) - someone from Holland who lived on Bermuda.

A cutter has three or more sails. Usually, the sail plan looks a lot like the sloop, but it has three headsails instead of one. Naval cutters can carry up to 6 sails.

Cutters have larger sail area, so they are better in light air. The partition of the sail area into more smaller sails give you more control in heavier winds as well. Cutters are considered better for bluewater sailing than sloops (although sloops will do fine also). But the additional sails just give you a bit more to play with.

Two-masted boats can have an extra mast in front or behind the mainmast. If the extra mast is behind (aft of) the mainmast, it's called a mizzenmast . If it's in front of the mainmast, it's called a foremast .

If you look at a boat with two masts and it has a foremast, it's most likely either a schooner or a brig. It's easy to recognize a foremast: the foremast is smaller than the aft mast.

If the aft mast is smaller than the front mast, it is a sail plan with a mizzenmast. That means the extra mast has been placed at the back of the boat. In this case, the front mast isn't the foremast, but the mainmast. Boats with two masts that have a mizzenmast are most likely a yawl or ketch.

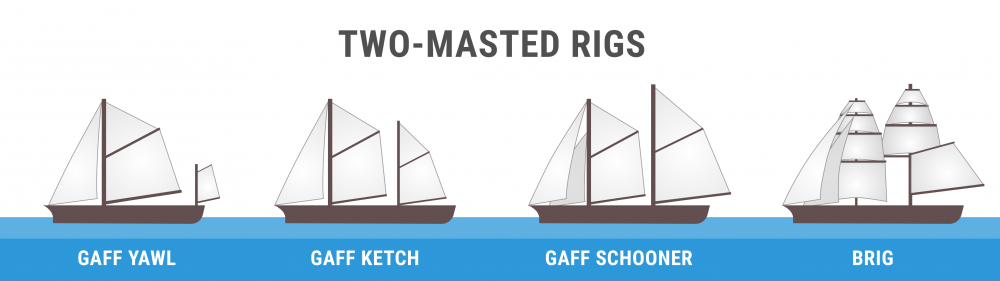

The two-masted rigs are:

- Lugger - two masts (mizzen), with lugsail (a cross between gaff rig and lateen rig) on both masts

- Yawl - two masts (mizzen), fore-and-aft rigged on both masts. Main mast is much taller than mizzen. Mizzen without a mainsail.

- Ketch - two masts (mizzen), fore-and-aft rigged on both masts. Main mast with only slightly smaller mizzen. Mizzen has mainsail.

- Schooner - two masts (foremast), generally gaff rig on both masts. Main mast with only slightly smaller foremast. Sometimes build with three masts, up to seven in the age of sail.

- Bilander - two masts (foremast). Has a lateen-rigged mainsail and square-rigged sails on the foremast and topsails.

- Brig - two masts (foremast), partially square-rigged. The main mast carries small lateen-rigged sail.

The yawl has two masts that are fore-and-aft rigged and a mizzenmast. The mizzenmast is much shorter than the mainmast, and it doesn't carry a mainsail. The mizzenmast is located aft of the rudder and is mainly used to increase helm balance.

A ketch has two masts that are fore-and-aft rigged. The extra mast is a mizzenmast. It's nearly as tall as the mainmast and carries a mainsail. Usually, the mainsails of the ketch are gaff-rigged, but there are Bermuda-rigged ketches too. The mizzenmast is located in front of the rudder instead of aft, as on the yawl.

The function of the ketch's mizzen sail is different from that of the yawl. It's actually used to drive the boat forward, and the mizzen sail, together with the headsail, are sufficient to sail the ketch. The mizzen sail on a yawl can't really drive the boat forward.

Schooners have two masts that are fore-and-aft rigged. The extra mast is a foremast which is generally smaller than the mainmast, but it does carry a mainsail. Schooners are also built with a lot more masts, up to seven (not anymore). The schooner's mainsails are generally gaff-rigged.

The schooner is easy to sail but not very fast. It handles easier than a sloop, except for upwind, and it's only because of better technology that sloops are now more popular than the schooner.

The brig has two masts. The foremast is always square-rigged. The mainmast can be square-rigged or is partially square-rigged. Some brigs carry a lateen mainsail on the mainmast, with square-rigged topsails.

Some variations on the brig are:

Brigantine - two masts (foremast), partially square-rigged. Mainmast carries no square-rigged mainsail.

Hermaphrodite brig - also called half brig or schooner brig. Has two masts (foremast), partially square-rigged. Mainmast carries a gaff rig mainsail and topsail, making it half schooner.

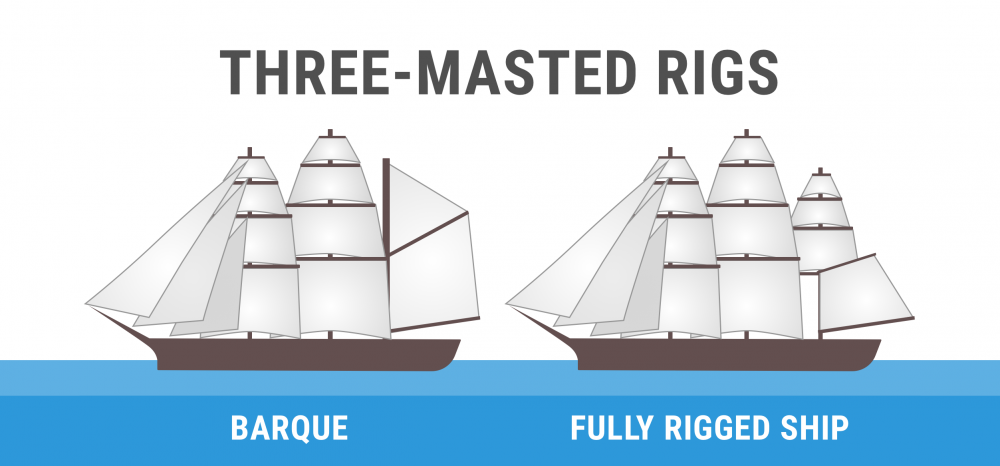

Three-masted boats are mostly barques or schooners. Sometimes sail plans with two masts are used with more masts.

The three-masted rigs are:

- Barque - three masts, fore, and mainmast are square-rigged, the mizzenmast is usually gaff-rigged. All masts carry mainsail.

- Barquentine - three masts, foremast is square-rigged, the main and mizzenmast are fore-and-aft rigged. Also called the schooner barque.

- Polacca - three masts, foremast is square-rigged, the main and mizzenmast are lateen-rigged.

- Xebec - three masts, all masts are lateen-rigged.

A barque has three or four masts. The fore and mainmast are square-rigged, and the mizzen fore-and-aft, usually gaff-rigged. Carries a mainsail on each mast, but the mainsail shape differs per mast (square or gaff). Barques were built with up to five masts. Four-masted barques were quite common.

Barques were a good alternative to full-rigged ships because they require a lot fewer sailors. But they were also slower. Very popular rig for ocean crossings, so a great rig for merchants who travel long distances and don't want 30 - 50 sailors to run their ship.

Barquentine