ROBERT VESCO: HIS YEARS ON THE RUN // He used up friends, money

- DAVID ADAMS

It was late 1982 and Robert Vesco, the fugitive financier wanted in the United States for stealing more than $200-million, had done it again.

After 10 years of a mercurial exile on the run, he had dropped out of sight.

His millions had bought him protection everywhere he went _ Costa Rica, the Bahamas, Antigua, Nicaragua. It was a nation-hopping odyssey straight out of a James Bond movie. But he was running out of friends . . . and money. Reports were that he was also seriously ill.

Three years passed before he reappeared in August 1985. When an American television crew finally caught up with him, the worst fears of U.S. officials were confirmed. Vesco, the rogue capitalist, had found refuge in Cuba, the rogue communist state. Protected by Fidel Castro, he was about as far out of the reach of American justice as money can buy.

Or so it seemed until a month ago, when, in a sudden, unexplained turnaround, his hosts became his captors.

Until his arrest in Cuba, Vesco, 59, had seemed assured of ending his days in relative comfort and obscurity.

A household name in the 1970s, memories of his pioneering role in the Wall Street world of financial swindles had dimmed, his reputation overtaken by the likes of Michael Milken and Charles Keating.

But his ability over 23 years to stay one step ahead of his pursuers, ensured him legendary status in law enforcement circles as the king of white-collar crime. U.S. officials tracked his movements around the Caribbean ever since he fled in the early '70s after the Securities and Exchange Commission charged him with plundering a mutual fund he controlled of $224-million. At the time it was the largest and most bewildering fraud case of its kind. Vesco was also indicted for giving an illegal $200,000 contribution to President Richard Nixon's re-election campaign in 1972.

Vesco subsequently engaged in numerous alleged criminal escapades while on the run, amassing further charges including drug running and illegal smuggling in breach of the U.S. trade embargo against Cuba.

Due to the cloak of official secrecy that surrounded Vesco's presence in Cuba after 1983, little is known of his existence there. Most accounts paint a portrait of a millionaire who dazzled the Cuban nomenklatura with fancy dinners aboard his yacht. The Cubans rewarded him handsomely for invaluable help in shady financial deals to skirt the U.S. embargo.

But, according to author Arthur Herzog, "the myth of Robert Vesco as a brilliant if crooked financier, courted by Caribbean governments and sitting on a fortune of embezzled money, is largely the creation of Mr. Vesco himself, with a little help from overzealous United States prosecutors."

In his book, Vesco: From Wall Street to Castro's Cuba, Herzog argues that Vesco made off with far less money than prosecutors claim and that he squandered his assets in bad investments and bribes in Costa Rica and the Bahamas. By the time he reached Cuba, most of the money was gone.

Mechanic's son

Vesco's life began uneventfully enough. The son of a Detroit auto mechanic, he married at 17 and enrolled at a technical school. But his fortunes took a dramatic change after he dropped out.

A machine-tool company with one key product, a specialized valve for aerospace applications, provided his big break. His business interests widened as he displayed an uncanny ability to make impossible deals.

"He did it with mirrors _ dummy corporations, tricky transfers of stock powers, rigged shareholders meetings," says Herzog.

Through his Florida company, International Controls Corp., he launched a skillful $5-million bailout of a lucrative mutual fund company, Investors Overseas Services (IOS), which had assets of more than $400-million, but had been suffering from mismanagement.

Its problems quickly worsened under Vesco's control. Assets began to vanish.

Vesco clearly knew what he was doing and that one day he would have to make a run for it. According to the Securities and Exchange Commission, which began investigating Vesco in 1972, he drained off IOS funds by selling assets to shell companies he controlled. Money was funneled to Panama through a bank in the Bahamas. From there it disappeared.

In 1972, so did Vesco.

His first stop was Costa Rica. According to local newspaper reports he arrived with his wife, Patricia, and several children, aboard his personal Boeing 707, that boasted a disco and sauna.

Shortly after his departure he sent a courier bearing $200,000 in cash to Maurice Stans, Commerce Secretary and a top fund-raiser for President Nixon. Prosecutors alleged that Vesco tried to bribe Stans and Attorney General John Mitchell to drop the investigation of his dealings at IOS.

In Costa Rica, Vesco installed himself in a fortress-like residence with closed-circuit cameras and a private security force. He drove around the capital, San Jose, in a gray Mercedes with four Land Rovers as escort.

The United States made the first of several extradition requests. But Vesco had already bought protection, investing millions in local businesses, including a farm owned by President Jose Maria Figueres.

He and his family were issued Costa Rican passports and the national congress passed a new law making it harder to extradite foreigners.

But when a presidential candidate in the 1978 election used his campaign to attack Vesco's presence, it was time to leave.

Vesco moved again, this time to the Bahamas, where he had friends with influence, including senior officials in the government of Prime Minister Lynden Pindling.

But when the United States began to suspect that Vesco and government officials were involved in drug trafficking, the Bahamian government decided he was a liability and expelled him.

A.K.A. Tom Adams

Through business friends with dealings in Cuba, Vesco had already met several senior Cuban officials. Vesco was able to convince them that his business expertise and connections in the world of high-tech finance could be of enormous value to Cuba's efforts to thwart the U.S. embargo.

He moved secretly to Cuba with his family in 1983, taking on a new identity: Tom Adams. He was assigned a state-owned villa at the exclusive Marina Hemingway on the western outskirts of Havana.

Vesco's stocky figure, dressed in oversized khaki Bermuda shorts and leather sandals, became a familiar sight at the marina. Tom "el Americano" was a regular at the best night spots and on the golf course. He also built an expensive beach house on Cayo Lago on the southern coast.

His children attended the private international school in Havana and would later study abroad, in Europe and the United States.

But Herzog _ the only person to have interviewed Vesco in Cuba _ suspects that he never lived up to Cuban expectations of him, and that by the late 1980s, he had ceased being of much use to Castro.

They met in a small, dimly lighted park in 1986. "I noticed seven or eight bodyguards trailing us," said Herzog. Vesco took him to a modest, two-story house. "Having seen where he lived I would not say that it was luxurious. He had a boat in Cuba, but I think the Cubans confiscated it," he said.

Herzog, and others familiar with Vesco's Cuban years, believe most of the deals he tried to arrange in Cuba fell through. In 1983, together with an old Detroit school pal, he unsuccessfully attempted to smuggle $730,000 worth of sugar-processing machinery to Cuba from the United States. Customs officials in Texas seized the shipment and accused Vesco of "trading with the enemy."

Reportedly, Vesco pocketed $300,000 from the deal. That did not sit well with some Cuban officials who protested that Vesco was stealing from the Castro government. Somehow he survived the affair, but his ability to make future deals may have been irrevocably damaged.

In the late 1980s he allegedly turned to drug trafficking, in desperation perhaps over the state of his personal finances.

The Medellin cartel

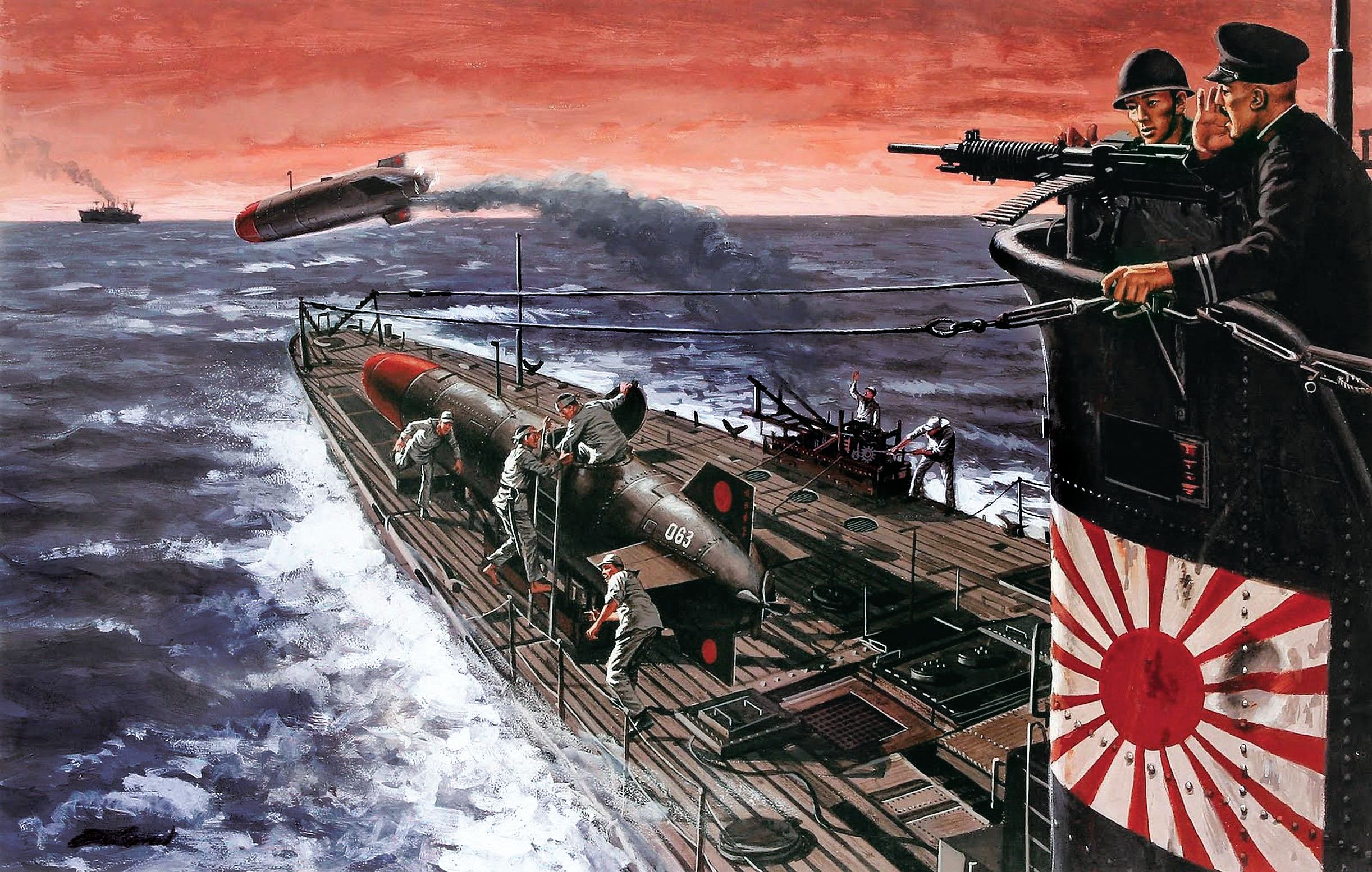

According to a 1989 Jacksonville indictment, Vesco played a key role in early contacts between Cuban officials and Colombian drug traffickers.

While in the Bahamas, Vesco had befriended Carlos Lehder, an infamous drug lord from the Colombian city of Medellin. When Lehder needed permission to fly drug planes over Cuban airspace, he turned to Vesco.

According to court records, Lehder sent his own pilot to Havana with a letter for Vesco, asking him to approach Cuban authorities. A few days later, Lehder had the answer he wanted, and the drug flights began.

Lehder was later arrested and jailed in the United States for drug trafficking. In 1991, he testified at the Miami drug trial of the Panamanian dictator, Manuel Noriega. Vesco "was one of my partners in the Bahamas," Lehder told the court. During a visit to Cuba, Lehder claimed he and Vesco "discussed money laundering and discussed the use of the island as a trans-shipment point."

Evidence of the Cuban drug connection was deeply embarrassing for Castro and he responded by staging a crackdown. After a notorious show trial in 1989, several top Cuban officials were executed for treason, including some of Vesco's contacts.

Under arrest

Although Vesco's name was never officially mentioned by Cuban officials, after the trial he suffered a notable fall from grace. He and his family were moved out of their residence to a smaller house, not far from Castro's own mansion. Vesco was placed under virtual house arrest.

In 1993, Herzog says Vesco took a secret trip to Moscow, armed with the usual shady business deals, and with a view to immigrating to the former Soviet Union. He was sent packing back to Havana.

Now, after 23 years, his elusive flight from justice appears to be over, albeit in a Cuban jail cell. His life on the lam has come full circle. With him at the time of his arrest was Donald Nixon Jr. a nephew of the late president.

Hopes that Cuba might turn Vesco over to U.S custody were quickly dashed when Castro told CNN that it would be "immoral" for Cuba to deport him. Cuban officials have refused to discuss details of the case, except to say that he is being detained on suspicion of being an "agent for special foreign services." They have not indicated for which country's intelligence service Vesco may have been working.

Precisely why he was arrested remains unclear. Some think Castro is seeking to curry favor with Clinton in the wake of a new immigration agreement in May that some say signifies a new warming in relations between Washington and Havana?

Others suspect Vesco may simply have been up to his old tricks.

"Wouldn't it be a marvelous irony if in the end what undid Vesco was that the Cubans found out he was ripping them off, too?" observes one U.S. official monitoring the case.

Vesco's years on the run

Financier Robert Vesco is under arrest in Cuba after more than 20 years as a fugitive.

1950: Son of Detroit auto worker. Dropped out of Detroit technical school circa 1950.

Early '70s: Flees to Bahamas to avoid SEC probe.

1972: Makes $200,000 contribution to Richard Nixon's re-election campaign. Built financial empire. Fell from grace after crash of his Geneva-based mutual fund.

1973: In San Jose, Costa Rica, running coffee-bag manufacturing company with official government protection.

1974: Indicted by N.Y. federal grand jury for stealing $224-million in mutual funds.

1978: Expelled from Costa Rica and shows up in Bahamas. Linked to drug trafficking. Set up Bahamas Commonwealth Bank which collapsed 1981.

1982: Sighted in this Caribbean island of Antigua briefly; U.S. seeks extradition. Shows up in Nicaragua where he begins to get involved in drug trafficking.

1983: Trading with the enemy. Vesco named in Texas investigation into illegal smuggling of $730,000 of sugar industry machinery to Cuba. Seen in Havana; luxury existence aboard yacht at Marina Hemingway on outskirts of Havana. Presence there confirmed in 1985. Alleged involvement in drug trafficking, money laundering and embargo busting.

1989: Named in Medellin cartel drug indictment by Florida federal grand jury in Jacksonville fro drug smuggling.

1995: Arrested in Cuba; may be extradicted to U.S.

Source: News reports; research by PAT CARR

MORE FOR YOU

- Advertisement

ONLY AVAILABLE FOR SUBSCRIBERS

The Tampa Bay Times e-Newspaper is a digital replica of the printed paper seven days a week that is available to read on desktop, mobile, and our app for subscribers only. To enjoy the e-Newspaper every day, please subscribe.

- Latin America

- Expat Living

- Art and Culture

- Science and Tech

- Classifieds

- Advertise with Us

COSTA RICA'S LEADING ENGLISH LANGUAGE NEWSPAPER

Costa Rica Contractor Under Investigation for Prohibited Practices

Costa rica crocodile attack during nesting season turns deadly, costa rica braces for doubling of migrant influx in coming year, costa rica bridges, restrictions part of traffic fix, volunteers in costa rica team up to shield national park from blazes, robert vesco: ‘the whale in the puddle’.

F rom the day Robert Vesco arrived in Costa Rica in 1972 until his departure five years later, hardly a week went by that his name wasn’t in the headlines. The fugitive U.S. financier, accused in the U.S. of looting Investors Overseas Services (IOS) of $224 million, and his six associates moved his troubled financial empire here from his earlier haven in the Bahamas on invitation of then- President José (Pepe) Figueres, hoping to set up a “financial district” with its own set of laws – a “country within a country” to serve as a refuge for international funds of dubious origin.

Don Pepe’s determination to champion Vesco disillusioned many admirers of the visionary leader who led Costa Rica’s 1948 revolution, instituted the country’s modern democracy and abolished its army. But the feisty three-time President defiantly shrugged off all criticism, saying Costa Rica needed investments and shouldn’t question their source.

Vesco wasted no time repaying his hosts. Shortly after arriving with his yacht and lavishly- appointed Boeing 707, he moved his wife Pat and children Danny, Tony, Dawn and Bobby (son Patrick was born here) into a luxurious, heavily guarded walled home office compound in the eastern suburb of Curridabat and invested in numerous Figueres family operations. He bought bars, restaurants and casinos, invested in radio and TV stations through bearer-share corporations, acquired a large spread, complete with airport, in the northern province of Guanacaste, and even bought Country Day School from its founders, Robert and Marian Baker, to set up a center for children with learning disabilities so Bobby would receive specialized instruction.

He also financed Excelsior, a daily newspaper created as a voice for Figueres’ National Liberation Party to compete with the leading daily La Nación. In one of the decade’s biggest scandals, the controversial paper folded after racking up mountainous debts; its owners were never identified and government funds earmarked for poverty programs were used to pay off its employees.

Legendary Largesse

The financier’s largesse quickly became legendary – his name was linked (accurately or not) to almost every new venture, and communities throughout the country proclaimed themselves pro-Vesco because he had bankrolled local projects. At one point his investments here were believed to total between $25 million and $60 million.

In 1974 The Tico Times published an exclusive interview with “The Man Behind the Myth,” which revealed him as articulate, wily, cocky and wryly humorous. Already he was making a career of battling what he termed “political persecution” here and in the U.S., and would grow increasingly bitter as pressure against him mounted.

The U.S. had requested his extradition based on an allegedly illegal $200,000 contribution to the campaign of U.S. President Richard Nixon, but at the end of Figueres’ term, the so-called “Vesco Law” was hastily pushed through Costa Rica’s Congress, giving the presidency final say over extradition matters.New President Daniel Oduber, from Figueres’ Liberation Party, informed Vesco publicly that he could stay in Costa Rica as long as he respected local laws.

Costa Vesco

But Ticos were not happy about what the famous fugitive was doing to their country’s international image. One U.S. cartoon, widely reprinted here, showed a tourist arriving in “Costa Vesco”. Calling him “a whale in a puddle,” veteran local journalist Julio Suñol detailed the Vesco “takeover” in his book, “Robert Vesco Compra Una República” (“Robert Vesco Buys a Republic”.)

Both Guido Fernández, director of La Nación, and Rodrigo Madrigal, director of the daily La República, issued repeated calls for his ouster, alleging that he had tried to intervene in local politics and had ties to the Mafia. In the U.S, he was accused of negotiations to import 2000 submachine guns to Costa Rica and finance an arms factor with Figueres’ son, José Martí.

In 1976, The Tico Times published an exclusive interview with Vesco’s former pilot, Al (“Ike”) Eisenhauer, who had “hijacked” the financier’s Boeing in Panama and flown it to the U.S. at the request of U.S. officials, then wrote a book about his adventures with Vesco titled “The Flying Carpetbagger.” In the interview, Eisenhauer recounted many of Vesco’s shenanigans with the Figueres family, and described his former boss as “just a Detroit row-house kid.”

“I love that guy,” he said. “He’s the perfect bullshit artist – a genius.”

Meanwhile, elderly local architect Carlos Rechnitzer, who claimed he lost $250,000 in IOS, sued Vesco in local court, in a “Mouse that Roared” drama that dogged Vesco throughout his stay. In separate manifestos, 216 respected leaders and 5,000 citizens urged President Oduber to expel the financier as “harmful to the country,” and Congress began debating his ouster as an undesirable alien. Vesco spent his 39th birthday defending himself on national radio and TV.

From Bad to Tragicomic

A careless remark by Don Pepe during an interview with The New Republic magazine finally brought the curtain down on the Vesco Era, when he said Vesco had financed a “major part” of Oduber’s 1974 campaign. President and financier were summoned to testify before a legislative commission. La Nación and La República reported that companies connected to Vesco had received the lion’s share of profits from the 1975 nationalization of local gas distributors, and the clamor for his expulsion grew.

The situation went from bad to tragicomic when perennial maverick presidential candidate G.W. Villalobos wrapped himself in the Costa Rican flag and fired 60 shots into the wall of Vesco’s compound before being arrested.

In a futile effort to keep Vesco from becoming a campaign issue, Oduber went on national radio and TV to say he’d asked him to leave as soon as the lawsuit against him here was resolved.Vesco, however, applied for Costa Rican citizenship and said he hoped to stay. President-elect Rodrigo Carazo vowed to keep his campaign promise and expel him.

The local court hearing the Rechnitzer case made it easy one everybody (except Rechnitzer) by throwing out the lawsuit, freeing Vesco to leave, which he did three days before Carazo took office. The new President ordered Costa Rica’s borders closed to him, and his citizenship bid was rejected.

The “whale” eventually headed for a new haven in Cuba, but for years afterwards, “Vesco sightings” here were as common as Elvis sightings in the U.S. as the financier made several attempts to return to Costa Rica.

Weekly Recap

Costa rica weekly news recap march 17, 2024.

Latest Articles

Guatemala’s president arévalo welcomes new era of trust with us after years of tension, costa rica’s colón soars against dollar: lowest exchange rate in 14 years, miami open tennis tournament 2024: a spotlight on latin talent, costa rica launches first passenger drone flight in latin america, former costa rica minister luis amador announces self-imposed exile to canada amid corruption investigation.

For free real time breaking news alerts sent straight to your inbox sign up to our breaking news emails

Sign up to our free breaking news emails, thanks for signing up to the breaking news email.

When He wasn't sailing his 137ft yacht around the Caribbean, Robert Lee Vesco might be found dancing with mini-skirted women in a discotheque on the private Boeing 707 he called the Silver Phyllis. Since he did not appear to have any woman friend or relative of that name, aides assumed it was a play on the word "syphilis". A warning, perhaps, of the dangers its pleasures presented.

From the disco he would move to the sauna, the only one ever known to have been built on board an aircraft, and then to his private bedroom. Perchance to dream of his rise from metal shaper in a Detroit car factory, as the grandson of Slovenian and Italian immigrants, to one of the world's wealthiest men at 35.

Mr Vesco is now 60, and he has traded his favoured red velvet smoking jackets for a grey prison uniform in the Cuban state security prison, Villa Marista, in Havana. Awaiting verdict and sentencing on charges of economic fraud against the Castro regime, he could be in jail until he is 80, but at least, say diplomats, he is too old and ailing to be sent to one of the Caribbean island's notorious forced labour camps. In those, able-bodied prisoners are forced to cut sugar cane, barefoot, for 12 hours a day in blistering sun, according to human rights groups. A panel of five judges will decide whether Mr Vesco abused the Cuban state pharmaceutical industry by developing a would-be "miracle drug" - supposed to cure cancer, Aids and herpes and add years, perhaps decades, to a person's life by boosting the immune system - behind the government's back. He told the court the Cuban authorities were involved in the research for the drug, known as TX or Trioxidal.

According to Donald "Don-Don" Nixon, nephew of the late president and a long-time friend of Mr Vesco who was detained with him in Havana in May last year but later released, even relatives of Cuba's president, Fidel Castro, were involved in the research and test production at the state-run Labiofam lab in Havana. Mr Nixon described the drug as "the biggest breakthrough in the history of man, worth one billion dollars a month net" and said it had cured his own wife's cancer.

Once nicknamed "Swifty" or "Rapid Robert" by business associates because of the speed with which he could multiply his assets as well as the fast life he led, Mr Vesco has spent the last quarter century fleeing American justice. He was the "White Knight" who in 1970 "rescued" the late Bernie Cornfeld's Geneva-based Investors' Overseas Services, which asked: "Do You Sincerely Want to be Rich?" and promised: "I'll make you a millionaire."

Tempting small investors, IOS had become one of the world's biggest financial groups in the 1960s, but by 1970 it seemed on the brink of collapse, despite still controlling $400m (now pounds 258m) in funds. For $5m, "Swifty" took control of a financial hall of mirrors that was to push him into Fortune magazine's list of the world's wealthiest men, but would ultimately force him to live on the run.

While Mr Vesco was buying the plane and the $1.3m yacht, investors began noticing their returns were rapidly diminishing. Their concern deepened when they could not discover where their money was invested. The Securities and Exchange Commission found in 1972 that at least $224m of investors' money had vanished, presumably into Mr Vesco's own accounts. It charged him with fraud, and he became a fugitive. The custom-fitted Boeing 707, described as more luxurious than the US President's Air Force One, was impounded and eventually bought by Imelda Marcos, who was reported to have outbid Elvis Presley and Mick Jagger.

Mr Vesco flitted between the Bahamas, Costa Rica and Nicaragua until settling in Cuba in 1982, where President Castro accepted him "for humanitarian reasons". Calling himself Tom Adams, and living in Havana, close to Mr Castro's own mansion, he was known to neighbours as Tom el Americano.

His security appeared second only to that of el Jefe Maximo himself, with two carloads of heavily armed men following him everywhere and half a dozen extra "caddies" on the golf course. Whether the state-paid heavies meant he was friendly with President Castro was never clear, but in court last week Mr Vesco said he had never met the Cuban leader.

Diplomats at the US Interests Section in Havana said last week that Washington was still "interested" in having Mr Vesco extradited. Since the IOS money has probably evaporated, the most important charge would be one by the state of Florida that he helped to organise a "bridge" in Cuba for cocaine flights by the Medellin cartel from Colombia to the United States.

Carlos Lehder, a former Medellin cartel chief now in jail in the US, testified that Mr Vesco had acted as a middleman for cocaine shipments. Lehder's pilot, Carlos Fernando Arenas, also in jail, testified that Mr Castro's brother Raul, Cuban defence minister, met him and Mr Vesco to discuss the arrangement. Other sources said that Cuba used the returning cocaine planes to fly weapons to guerrillas of the pro-Cuba M-19 group in Colombia.

When the financier was arrested at his home last year, the Cuban authorities said he would face charges of being a "provocateur" and "an agent of foreign powers". By the time the court case started last week - it ended after three days - those charges had been dropped, and Mr Vesco was accused only of economic fraud centring on the "miracle drug". His second wife, Lidia Alfonso, a Cuban, faced similar charges.

Many diplomats in Havana believe the fraud charges may have been a smokescreen by Mr Castro to keep Mr Vesco behind bars, where he cannot talk. Some believe "Swifty" had planned to flee Cuba, perhaps to reveal what he knew of alleged Cuban involvement in drug trafficking. Others believe the trial is a battle for control of the drug TX in case its "miracle" properties prove to be true.

If Mr Vesco is convicted, his four children from his first marriage believe he will die in jail. In court, the 6ft 1in former owner of Silver Phyllis appeared to weigh around nine stone, almost six stone less than in his 1970s heyday. "We are worried about his health," his son Danny said. "We hope the Cubans will be compassionate with him."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

New to The Independent?

Or if you would prefer:

Want an ad-free experience?

Hi {{indy.fullName}}

- My Independent Premium

- Account details

- Help centre

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

A Last Vanishing Act for Robert Vesco, Fugitive

By Marc Lacey and Jonathan Kandell

- May 3, 2008

HAVANA Robert L. Vesco, the fugitive financier who spent most of his life eluding American justice, might even have managed to die on the sly.

Mr. Vesco, who was sentenced to a long prison term in Cuba in 1996 and was wanted in the United States for crimes ranging from securities fraud and drug trafficking to political bribery, died more than five months ago, on Nov. 23, from lung cancer, say people close to him. If so, it was never reported publicly by the Cuban authorities, who said Friday that they considered him a “nonissue.” American officials said Friday they knew nothing about his death.

“We don’t know that it occurred,” an American official said.

If Mr. Vesco indeed eluded the American authorities until his final day, it was the fitting end to his nearly four decades on the run. He was wanted for, among other things, bilking some $200 million from credulous investors in the 1970s, making an illegal contribution to Richard M. Nixon’s 1972 presidential campaign and trying to arrange a deal during the Carter administration to let Libya buy American planes in exchange for bribes to United States officials.

Mr. Vesco last made the news a decade ago when he was sentenced to prison in Cuba, where he had taken sanctuary, for a financial scheme. He emerged in recent years and lived a quiet life in Havana until he contracted lung cancer. After about a week in a hospital, friends say, he died and was buried in an unmarked grave.

Given the controversial nature of the man, none of his friends dared be identified for fear of running afoul of the Cuban authorities. While word of Mr. Vesco’s death could be the final ruse of a 72-year-old modern-day buccaneer who had every reason to drop off the radar, it would have to be an elaborate one.

Records at Colón Cemetery in Havana indicate that a Robert Vesco was buried there on Nov. 24, and photographs and videos viewed by The New York Times show a man resembling him in a casket with his longtime Cuban companion looking over him.

Other photos show him coughing and clearly in pain in a hospital bed on what a friend said was the day before he died. There are also photos of a small group of people attending his burial.

His last days, a friend said, were in marked contrast to his ebullient pre-prison phase, when he partied lavishly, chain smoked and talked big.

Some of those who knew Mr. Vesco said it would not surprise them if he had orchestrated a fake death, to slip away one more time. “He could have died,” said Arthur Herzog, an author who interviewed Mr. Vesco in Cuba for a biography. “But Bob has used disguises in the past.”

On top of that, Mr. Herzog said, an intermediary who lives on the island had left the impression that he was in contact with Mr. Vesco in Cuba within the last month.

After a criminal odyssey that began on Wall Street, Mr. Vesco fled the United States in 1971, along the way repeatedly demonstrating the power of money to overcome any ideology.

His associates and protectors included democratically elected presidents in Costa Rica, the left-wing Sandinistas in Nicaragua, the cocaine barons of Colombia, the terrorism-tainted government in Libya, and, finally, the Communist government of Fidel Castro.

Whereas the American government considered Mr. Vesco to be an American fugitive, he had apparently somehow gained Italian citizenship. A friend provided a copy of an Italian passport issued in 2006 that bore Mr. Vesco’s name and photograph.

The friend said representatives from the Italian Embassy had visited Mr. Vesco while he was in jail and had assisted with his funeral arrangements. An Italian Embassy official did not return calls seeking comment.

Having lived comfortably in Havana for more than a dozen years, Mr. Vesco was convicted and jailed there for fraud in 1996 after reportedly double-crossing Fidel Castro’s relatives in a bogus wonder-drug deal.

How much truth there was to the allegation was impossible to know for certain because accusations against the shadowy financier have always seemed to mix rumor and fact.

At the height of his notoriety in the 1970s, Mr. Vesco looked like a tough guy out of Hollywood central casting tall, craggy-faced, with a mustache, long sideburns and sunglasses. He liked to burnish his image as an unpredictable rogue driven as much by perverse pride as by crass profit.

He also delighted in thumbing his nose at Cuban agents who were on his trail. They responded by suggesting that Mr. Vesco was the mastermind behind every sort of money-laundering, narcotics and smuggling plot in the Caribbean.

“With even a fraction of what he was supposed to have stolen he could have disappeared,” wrote Mr. Herzog, in his 1987 biography, “Vesco: From Wall Street to Castro’s Cuba, The Rise, Fall and Exile of the King of White Collar Crime.”

Instead, Mr. Vesco seemed to have a compulsion to call attention to himself from his places of exile. A self-made man, he seemed hardly able to help it.

A high school dropout from Detroit, he lied about his age to get a job on an automobile assembly line. At 21, he moved to New Jersey to work for a struggling manufacturer of machine tools.

He took over the company when it went bankrupt, rebuilt it and renamed it the International Controls Corporation. By the age of 30, Mr. Vesco was a millionaire.

He later turned his sights on a Switzerland-based mutual fund company, Investment Overseas Services (I.O.S.). When that, too, ran into trouble, Mr. Vesco offered to rescue the company and was embraced as a white knight by investors terrified of losing their savings.

He bought I.O.S. in 1970 for less than $5 million, gaining control of an estimated $400 million in funds. The accounting at the company had been so chaotic that Mr. Vesco, by adding a few subterfuges of his own, was able to plunder its holdings at will.

After numerous complaints, the United States Securities and Exchange Commission carried out an investigation. In 1972, the commission charged Mr. Vesco and others in a civil suit with stealing more than $224 million.

But Mr. Vesco had already fled, first to the Bahamas and then to Costa Rica. There, he established a close friendship with President José Figueres, plowing some $11 million into his adopted country.

“I wish more Vescos would come to Costa Rica we need them,” said Mr. Figueres on television in response to criticism that he was harboring a criminal.

Mr. Vesco also befriended Donald A. Nixon Jr., a nephew of President Richard M. Nixon, and gave $200,000 to the Nixon campaign, apparently hoping the president would help quash the investigation against him.

It was to no avail. But to the frustration of the F.B.I. Mr. Vesco remained tantalizingly out of reach in Costa Rica, where he passed himself off as a progressive dairy and cattle rancher, and an investor in high-tech projects.

Eventually, one of his high-tech brainstorms a factory to make machine guns, which included President Figueres’s son as a partner became his undoing.

A public and political outcry ensued, and by 1978 he was forced to leave for the Bahamas, the beginning of years of hopscotching that included stops in Antigua and Nicaragua, before Cuba finally accepted him for “humanitarian” reasons.

“We don’t care what he did in the United States,” Fidel Castro said. “We’re not interested in the money he has.”

In Cuba, Mr. Vesco grew a beard, donned a white guayabera shirt and passed himself off as a Canadian citizen named Tom Adams. He and his family lived in a suburban Havana house that was modest by United States standards but lavish for Cubans. Within a few years, allegations began to circulate about Mr. Vesco’s involvement in narcotics trafficking, and he was named as a co-conspirator in the trial in Florida of Carlos Lehder Rivas, a reputed leader of Colombia’s biggest drug cartel.

Mr. Vesco eventually ran afoul of the Castro government with a scheme to produce a wonder drug that supposedly cured cancer, AIDS, arthritis and even the common cold. He was accused of defrauding a state-run biotechnology laboratory run by Fidel Castro’s nephew, Antonio Fraga Castro, and sentenced to 13 years. After serving most of his time in a private cell in a large prison in eastern Cuba, Mr. Vesco was quietly released in 2005 and lived so simply in recent years in Havana that a friend said he did not know what had happened to his fortune.

Marc Lacey reported from Havana, and Jonathan Kandell from New York.

- Latest News

- Latest Issue

- Asked and Answered

- Legal Rebels

- Modern Law Library

- Bryan Garner on Words

- Intersection

- On Well-Being

- Mind Your Business

- My Path to Law

- Storytelling

- Supreme Court Report

- Adam Banner

- Erwin Chemerinsky

- Marcel Strigberger

- Nicole Black

- Susan Smith Blakely

- Members Who Inspire

- Robert Vesco, Famed Fugitive, May Have Died…

Robert Vesco, Famed Fugitive, May Have Died in Cuba

By Martha Neil

May 6, 2008, 9:22 pm CDT

A famous fugitive for decades after the publicity surrounding the Watergate scandal helped make him a household name, Robert Vesco reportedly may be dead at age 71 or 72. But although major news organizations have published his obituary, officials aren’t positive that the notorious con man and claimed associate of Latin American presidents, Soviet spies and even the CIA is actually deceased.

“I’m not certain he’s dead,” writer Arthur Herzog, who once interviewed Vesco for a biography, says in an Associated Press obituary today. Herzog says he recently talked with a Havana contact, who says he spoke with Vesco months after he reportedly may have died.

The New York Times , which first reported Vesco’s apparent demise, says a reporter saw photos and videos of an apparently ailing Vesco and what seems to have been his burial.

According to the Times and Reuters , relatives of Vesco say he died of lung cancer in Havana on Nov. 23 and was buried the next day. His family is still looking for his money, one relative tells Reuters.

Vesco is wanted in the U.S., where he is charged with looting $224 million from a Swiss-based mutual stock fund’s investors. He also allegedly contributed $200,000 to former President Richard M. Nixon’s 1972 campaign, in an effort to fend off a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission investigation, the AP recounts.

He was implicated as well in a scheme to bribe U.S. officials to allow Libya to buy American planes during the administration of former President Jimmy Carter, the New York Times notes.

Vesco was eventually imprisoned in Cuba, where he and his family lived for a time in an offshore yacht, after being convicted of marketing an alleged AIDS and cancer-curing drug without government permission. “His business partner, Donald A. Nixon Jr.—nephew of former President Nixon—was detained along with Vesco but was later released,” the AP writes.

Related topics:

Criminal justice | international law | careers | sentencing/post conviction | obituaries, you might also like:.

- Steven M. Wise, legal force for animal rights, dies at 73

- Justice O'Connor's judicial-reform push followed regret over 2002 decision

- Former Justice Sandra Day O’Connor dies at 93

- Former 3rd Circuit judge, Trump's sister, dies at age 86

- Florida lawyer dies in skydiving incident

Give us feedback, share a story tip or update, or report an error.

- New bar passage stats show several law schools below ABA cutoff

- Lawyer's joint sex with boyfriend and his daughter was 'tantamount to rape,' despite plea deal, disbarment order says

- This state is creating a way to skip the bar exam and making it easier to pass for those who take it

- Which law schools will top the US News rankings? Here are three predictions

- Lawyer disbarred for filing documents while suspended for firing employees to save his marriage

Topics: Career & Practice

What are 'reasonable measures' to prevent law firm conflicts? New ABA ethics opinion explores

Writing advice for lawyers from nonlawyers

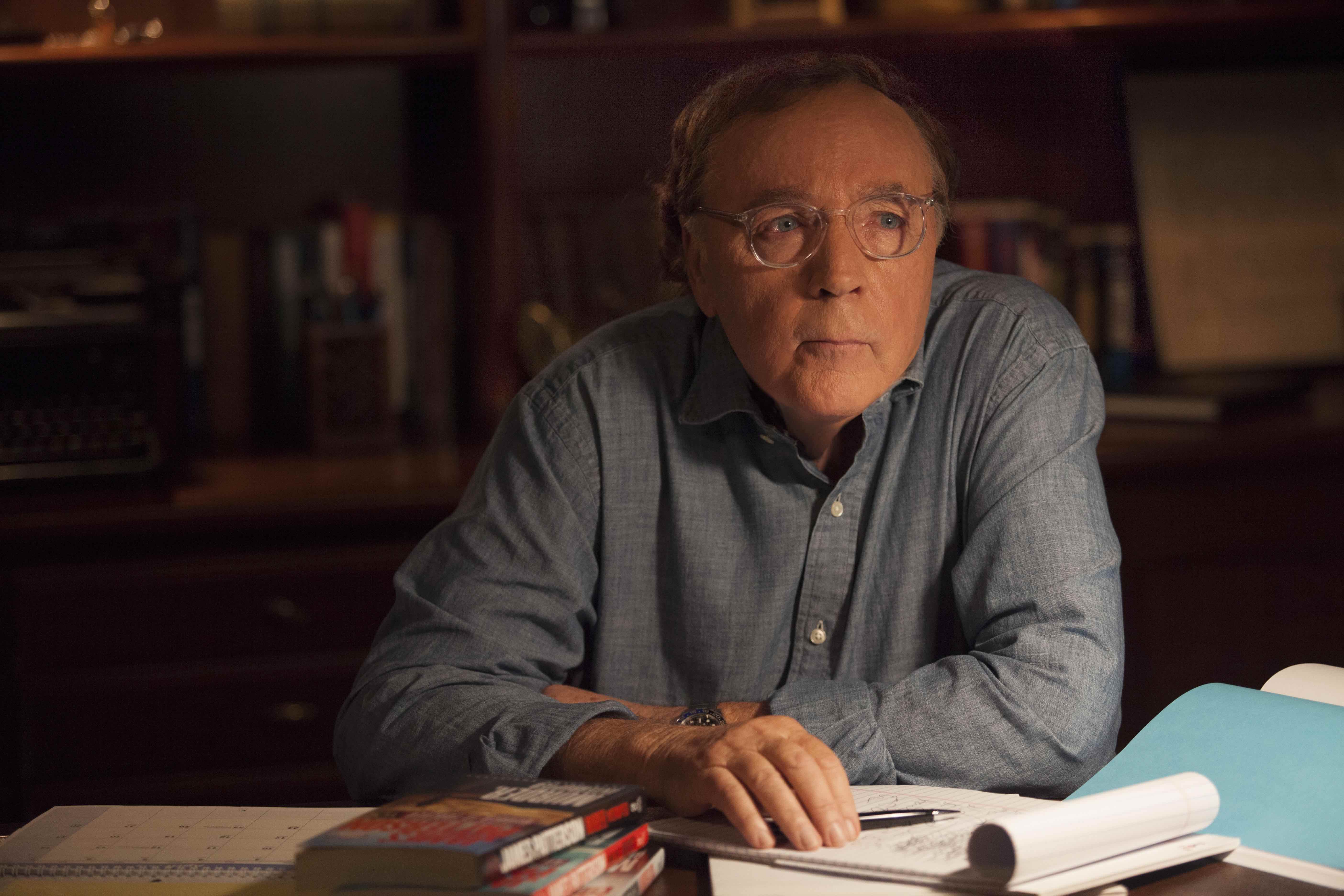

James Patterson dishes on his new legal thriller, 'The #1 Lawyer'

- Nation & World

Did longtime fugitive Robert L. Vesco elude U.S. even in death?

Robert L. Vesco, the fugitive financier who spent most of his life eluding American justice, may even have managed to die on the sly. Vesco, who was sentenced...

Share story

HAVANA — Robert L. Vesco, the fugitive financier who spent most of his life eluding American justice, may even have managed to die on the sly.

Vesco, who was sentenced to a long prison term in Cuba in 1996 and was wanted in the United States for crimes ranging from securities fraud and drug trafficking to political bribery, died more than five months ago, on Nov. 23, from lung cancer, say people close to him.

If so, it was never reported publicly by Cuban authorities, contacted Friday. U.S. officials said Friday they knew nothing about it. “We don’t know that it occurred,” a U.S. official said.

If Vesco in fact eluded U.S. authorities until his final day, it was the fitting end to his nearly four decades on the run. He was wanted, among other things, for bilking some $200 million from credulous investors in the 1970s, making an illegal contribution to Richard Nixon’s 1972 presidential campaign and trying to induce the Carter administration to let Libya buy American planes in exchange for bribes to U.S. officials.

Most Read Nation & World Stories

- Ruth Bader Ginsburg award ceremony canceled after fallout over honorees

- Supreme Court rules in favor of Oregon man who challenged no-fly listing

- Sports on TV & radio: Local listings for Seattle games and events

- Court order puts Texas law allowing police to arrest migrants who cross illegally back on hold

- Jared Kushner, Trump's son-in-law, praises 'very valuable' potential of Gaza's 'waterfront property'

Vesco last made the news a decade ago when he was sentenced to prison in Cuba, where he had taken sanctuary, for a financial scam. He emerged in recent years and lived a quiet life in Havana until he contracted lung cancer. Friends say he died after about a week in a hospital and is buried in an unmarked grave.

Given the controversial nature of the man, none of his friends dared be identified for fear of running afoul of Cuban authorities. While word of Vesco’s death could be the final ruse of a 72-year-old, modern-day buccaneer who had every reason to drop off the radar, it would have to be an elaborate one.

Records at Colon Cemetery in Havana indicate that a Robert Vesco was buried there on Nov. 24, and photographs and videos viewed by The New York Times show a man resembling him in a casket with his longtime Cuban companion looking over him.

Other photos show him coughing and clearly in pain in a hospital bed on what a friend said was the day before he died. There are also photos of people attending his burial.

His last days, a friend said, were in marked contrast to his ebullient pre-prison phase, when he partied lavishly, chain-smoked and talked big.

Some of those who knew Vesco said it would not surprise them if Vesco had orchestrated a fake death, to slip away one more time. “He could have died,” said Arthur Herzog, an author who interviewed Vesco in Cuba for a biography. “But Bob has used disguises in the past.”

On top of that, Herzog said, an intermediary who lives on the island had left the impression that he was in contact with Vesco in Cuba within the past month.

While the U.S. government considered Vesco an American fugitive, he had apparently somehow gained Italian citizenship. The friend said representatives from the Italian embassy had visited Vesco while he was in jail and had assisted with his funeral arrangements. An Italian embassy official did not return calls seeking comment.

clock This article was published more than 28 years ago

ROBERT VESCO AND THE END OF THE RUN

The sec is dusting off 23- year-old case files on the fugitive financier.

If the Securities and Exchange Commission had a Most Wanted List, Robert Vesco would be the entire Top 10.

For 23 years, Vesco has been running from the SEC and a posse of pursuers that has grown steadily as the fugitive financier was accused of new crimes committed while he tried to stay ahead of the law.

Over two decades, Vesco set the standards for multinational financial crime: To regulators, he was a master at building cross-border corporate networks to escape government oversight, a magician who made millions disappear by bouncing the money from company to company, country to country, until it could not be traced.

Vesco got away with $224 million, most of it in cash, the SEC charged in the original 1972 civil complaint against him. At the time, it was the biggest financial fraud case the SEC had ever filed -- the equivalent of more than $800 million in today's dollars.

Vesco has been on the lam so long that the documentation amassed against him is filed away "in some place out of Raiders of The Lost Ark,' " said William McLucas, the SEC enforcement director who may finally have a chance to put the long-sought Vesco on trial.

The files were dusted off yesterday after U.S. diplomats learned that Vesco had been arrested by Cuban authorities. Cuba has agreed to deport him to the United States to face drug smuggling charges linking him to the Colombian cocaine cartel, officials said. The Justice Department began preparing extradition papers yesterday in anticipation of taking custody of Vesco {Details, A14}.

Federal law enforcement agencies have not yet decided who gets first crack at Vesco, but it was the SEC that sent him into exile with allegations that he looted Investors Overseas Services, a mutual fund that collapsed in the early 1970s.

Vesco faces the SEC civil lawsuit filed in 1972 that accused him of securities fraud in the IOS case, and a parallel criminal case filed in 1976.

In addition, McLucas said, Vesco still is under a 1982 court order to account for the money missing from IOS and to repay investors $392 million plus interest at the rate of 10.4 percent a year. That amounts to $1.4 billion today, and Vesco "is probably a little light," quipped McLucas.

The obligation to repay and the SEC charges "never go away," the SEC official said, and Vesco's legal problems are compounded by criminal charges stemming from his flight to avoid prosecution.

Others who have pursued Vesco over the years, however, say that resurrecting the IOS case will be difficult because records have been lost, key players in the scam have died and the officials who handled the IOS case have died, retired or gone on to other jobs.

The original case against Vesco was built by Stanley Sporkin, who was then the SEC's enforcement director and is now a U.S. District Court judge in Washington.

Sporkin became legendary for his pursuit of Vesco and Bernard Cornfeld, who ran Investors Overseas Services before Vesco. He spent years driving IOS out of the United States -- and Cornfeld out of IOS -- only to have the company fall into the hands of Vesco, who was accused of looting it even as the SEC closed in on him.

SEC officials were dubious about IOS from the very beginning, because the company was structured to charge investors twice as much in commissions and fees as other mutual funds.

Ordinary mutual funds take in cash from investors and use it to buy stocks in companies. IOS was a "fund of funds," meaning it invested its customers' money in other mutual funds that it owned. Cornfeld and his cronies took one set of commissions when they sold shares in the first fund and another set when they reinvested the investors' money in the funds IOS owned.

IOS posed regulators a challenge: It was incorporated in Canada, had its headquarters in Geneva, was actually run from offices in France and sold shares all over Europe.

Though not permitted to sell shares in the United States, IOS found ways to circumvent the restriction and targeted the large contingent of American soldiers serving in Europe during the 1960s. A key part of the company's sales pitch was that as an "offshore" fund, IOS investments could not be tracked by the Internal Revenue Service.

But accusations of tax evasion and double-dipping on fees paled in comparison to what regulators charged went on when Vesco took over IOS and began arranging transactions much like those used in savings and loan scandals a decade later.

He allegedly drained money out of IOS by shuffling assets from one related company to another. IOS would take a valuable investment and give it to another corporation in exchange for that corporation's stock. Then the second corporation would swap the investment for stock in a third corporation. The original asset would disappear and IOS would wind up holding worthless stock in two shell corporations.

None of the money missing from IOS has ever been found; most of it was traced into Panamanian banks and never seen again, officials who worked on the case said.

Vesco never appeared in court to answer any of the charges and never was seen in the United States after the SEC served him with a subpoena in the Bahamas in 1972.

"To tell you the truth, I was astounded he stayed away," said Washington lawyer John R. Wing, who was the chief prosecutor in a 1974 criminal case in which Vesco was accused of trying to fix the SEC case by giving an illegal $200,000 campaign contribution to President Nixon.

"When you think back over people who run, very few stay away. The United States is the best place in the world to live and he could have lived very well after serving his time," Wing said.

An SEC veteran pointed out that Michael Milken and Ivan Boesky, the best-known financial criminals of the 1980s, each served only two years in prison. That, he added, would have been far easier for Vesco than 20 years on the run, 10 years in Cuba and the possibility of spending the rest of his life behind bars. CAPTION: Robert Vesco in 1973. CAPTION: THE IOS ODYSSEY Robert Vesco's problems started in the early 1970s, when the Securities and Exchange Commission began investigating his business deals, including the possibility that he stole $224 million in the assets of a company he controlled, Investors Overseas Services Ltd. Here is a look at the worldwide tentacles that mutual fund company had: * Country of Incorporation: Canada. * Headquarters: Switzerland. * Main offices: France. Affiliate offices: Costa Rica; Bahamas; Panama; Netherlands; Antilles; Lichtenstein.

'Master of disguises' believed dead in Cuba

Robert Vesco, the American fugitive who cooked up moneymaking schemes that allegedly involved everyone from Colombian drug lords to the families of U.S. presidents, died in Cuba and was buried almost six months ago, according to an official document.

A burial record at Havana's Colon Cemetery shows that a man with the same name and birthdate — Dec. 4, 1935 — died on Nov. 23 from lung cancer and was buried the next day in a private plot. He was 72.

In his lifetime, Vesco was accused of looting millions from a Swiss mutual fund, attempting to find U.S. planes for Libya and inventing a drug that he claimed could cure AIDS.

He was linked to Latin American presidents, Soviet spies, smugglers of high-technology equipment — even the CIA.

And he was good at hiding.

Still alive but hiding? Writer Arthur Herzog, who once interviewed Vesco in Cuba for a biography, called him "a master of disguises," noting the infamous con man had long employed elaborate schemes to escape justice.

"I don't know for sure, but I'm not certain he's dead," Herzog said from his home in New York. He said he recently spoke with a contact in Havana who indicated he had talked with Vesco in recent weeks.

Vesco was so crafty, a DNA test on the buried corpse would be necessary to know for certain it was him, Herzog said.

U.S. officials in Cuba said Monday they were unaware of Vesco's death.

Vesco evaded American justice during a quarter-century odyssey through the Caribbean and Central America after fleeing the U.S. in 1972.

It was Cuban courts that finally put him in prison in 1996, convicting him of marketing a drug, which he claimed could cure cancer and AIDS, without government permission. His business partner Donald A. Nixon Jr. — the nephew of former President Nixon — was detained along with Vesco, but was later released.

Vesco ended up serving most of his 13-year sentence, though it was not clear when he was released.

Vesco is still wanted in the United States on charges of looting $224 million from a investors in a Swiss-based mutual stock fund.

He also was indicted for allegedly contributing $200,000 to Nixon's 1972 campaign to try to head off a probe by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Two Nixon Cabinet members were later tried and acquitted.

Renounced his U.S. citizenship Vesco renounced his American citizenship and traveled around the Caribbean and Central America in a yacht and various private planes — including a custom Boeing 707 equipped with a sauna.

He settled in Costa Rica, but was kicked out after a new president took office there in 1978.

Vesco moved to the Bahamas, but fled in 1981 aboard his U.S. $1.3 million yacht just before Bahamian authorities issued orders to deport him. In the United States, prosecutors accused him of plotting to pay a kickback to Billy Carter, brother of President Jimmy Carter, to win U.S. permission for Libya to buy C-130 military planes.

Vesco surfaced on the small Caribbean isle of Antigua in 1982 with a plan to buy half of Barbuda, Antigua's small sister island, and establish a principality called the Sovereign Order of New Aragon.

By the fall of that year he was living in Nicaragua. U.S. drug officials later said he collaborated with the Sandinista government to bring cocaine into the United States.

At the end of 1982, he came to Cuba, where he lived off the island of Cayo Largo aboard his yacht with his wife and children. The couple eventually separated and Vesco lived for years with a Cuban woman.

Vesco remained safe from U.S. justice in Cuba, which for decades has been at odds with the United States and refused repeated American requests to extradite him.

Cuban President Fidel Castro said in 1985 that his country allowed Vesco to come for medical treatment, accusing U.S. officials of persecuting the fugitive. "Is it right to harass a man like that?" he asked.

But Cuban officials began distancing themselves from him in the early 1990s after a U.S. federal indictment accused Vesco of working with Carlos Lehder, then reputed head of Colombia's Medellin drug cartel, to win Cuban permission for drug flights over the island.

- Make a Suggestion

- Report a Problem

- Get Information on Boat Slips

- Get Information on Commercial Spaces

- Register my Car or Bike

- Register my Storage Bin

- Register my Care Animal

- Association Documents

- Hemispheres Events

- Board Dashboard

- Resident Directory

- Staff Directory

- Hurricane Info

- Memories and Old Photos

- Suggestion box

- Activities Calendar

Our History

- Classifieds

- Information

- Website FAQ

- Notifications

- Local Events

Zoomline Fl-hallandale-hemispheres

History of THE HEMISPHERES

Zoomline Fl-Hallandale-Hemispheres

Old Brochures AND ADVERTISMENTS

Memories and OLD PHOTOS

This old postcard shows an earlier era. Of note, the large crowd around the bayside pool, the yachts at the Marina Restaurant, the painted deck over the Utilities building, the design on the top of the porte cocheres, the original configuration of the marina, prior to the lifts, which allowed larger boats, the absence of a high rise next door. If you can provide more accurate dating or descriptions, like the name of the restaurant, or what was the plan for the current BBQ area, please share them.

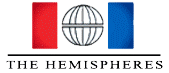

Plans for the The Hemispheres were submitted in 1967. It was designed by architect Robert C. West as a resort hotel offering long term leases. Bernard Cornfield, the head of Investors Over Seas Service organized a small group of foreign investors who controlled blocks of apartments, available for short term stays or long term leases. The Bay North Building opened in 1970. The other three buildings opened in 1972. Among early purchasers of long term leases was the family of Mazie Ford, once Florida's Oldest Living Person.

Bernard Cornfield, under investigation by the SEC, having problems getting financing for the other buildings, lost control of the IOC to Robert C. Vesco (who was also under investigation. In 1976 their activities and The Hemispheres was a major focus of a US House Committee investigating control of off shore owners. One of the issues involved The Hemispheres payment of grossly excess management fees to the company they controlled which managed La Mer at a fraction of the fees. Robert Vesco's infamous history is further detailed in the TIMELINE. The Hemispheres offered many amenities, including its own restaurants, membership in a golf club, a separate Yacht Club. Visit OLD BROCHURES.

In 1979 The Hemispheres sought to become a separate taxing district. The required vote was scheduled, then cancelled when it became clear that it might require open public access.

!n 2003, the Hemispheres opposed the development of the property to the north on the Bay side and the south on the Ocean side. They eventually reached an agreement with the 43-50 story Yacht Club developers preserving the sight lines. The following year, Shahab Karmely (KAR developers) purchased the property to the south of the Ocean South building and filed plans for a high rise. The Hemispheres accepted the plans in consideration of $1,300,000 compensation. Construction on the 39 story 2000 Condo began in 2019,

The same year The Hemispheres began reconstruction of the parking lot next to 2000 and its owners approved an assessment to replace the roofs and restore the porte cocheres on all four buildings. Included in that assessment was needed work in the Marina, and replacement of the air conditioning tower, chillers and handlers

As you can see, we've only just begun. Because few of the old records still exist, a more detailed history will depend on the help of previous BOD members and knowledgeable owners. -

Share a memory, an experience riding out a hurricane that came or never showed up, a memory of a restaurant, a famous public person who was here (no one who still is without their permission, please), events in Ballroom, a big fish caught off the pier, a favorite employee who has moved or passed on.

AND, of course, share PICTURES!

To share send via an email to H ISTORY (click here)

We have only just begun the history and factoids about The Hemispheres.

Contact Leonard Davenport at [email protected] or call 631-834-6919

From an early set (probably 1970) of sales sheets showing layouts of all the Bay North apartments and an indication that presales had begun for Bay South. Notice things like the free-form pool planned for the Ocean side. Does anyone know if it was that shape?

Please enter at least 3 characters

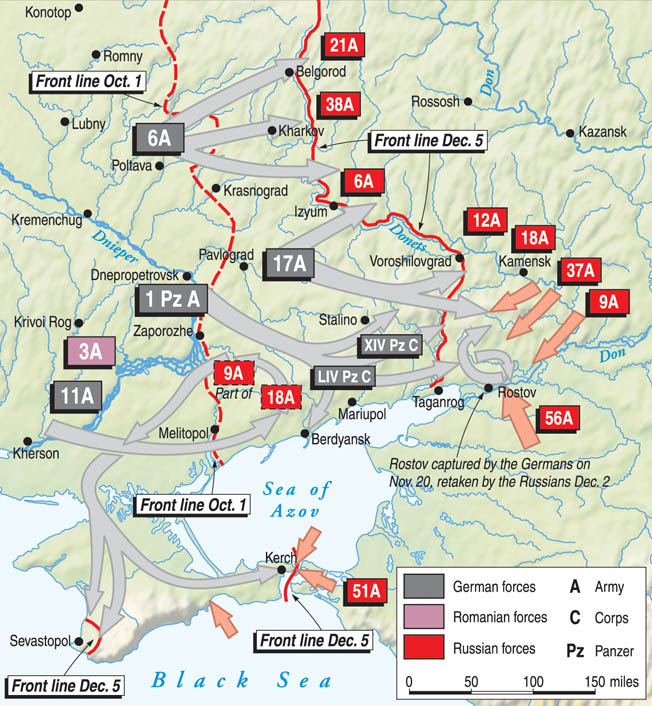

Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler’s Drive to the Don

In late 1941, a German thrust toward the city of Rostov and the River Don was blunted by strong Soviet counterattacks.

This article appears in: April 2014

By Pat McTaggart

Rostov was the key to the Caucasus and the rich Soviet oil fields that lay along the Black and Caspian Seas. No one could accuse Adolf Hitler of being underambitious. The great battles of encirclement at Kiev, Minsk, Uman, Smolensk, and other pockets had yielded hundreds of thousands of Russian prisoners during the first months of the 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union, otherwise known as Operation Barbarossa. Believing that Soviet Premier Josef Stalin was almost certainly finished, the German leader thought his armies were capable of even greater victories.

With that in mind, he ordered his eastern forces to continue attacking all across the vast front. In the north, Leningrad was the target. In the center it was Moscow, and in the south it was the Ukraine with its great agricultural and industrial resources. In conjunction with the capture of the Ukraine, Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt’s Army Group South was ordered to capture the Crimea and, at the same time, take the city of Rostov-on-Don and the bridges that spanned the mighty river on which it sat.

Rostov: An Old Trading City on the Don

On December 15, 1749, a small customs house had been established near the mouth of the Don River to help control trade with the Turkish Empire. A fortress was soon built on the site, and gradually the small town that sprang up in the area turned into a city full of tradesmen and merchants.

At the beginning of Barbarossa, Rostov was more than 1,000 kilometers behind Army Group South’s staging areas in Poland. The people of the city watched as troops headed for the front passed through almost daily. Soviet propaganda assured civilians that the Germans were being slaughtered by the thousands and that the enemy would soon be vanquished. In reality, the forces of Army Group South were assembling less that 400 kilometers away, ready to continue their victorious advance.

Von Rundstedt had done his job well. Lt. Gen. Dmitrii Ivanovich Riabyshev’s South Front and Lt. Gen. Mikhail Pertrovich Kirponos’s Southwest Front had been shattered in the previous months. Kirponos had paid with his life on September 20 when he was killed while trying to escape German forces. His replacement was the extremely capable Marshal Semyon Konstantinovich Timoshenko.

Although the Germans had inflicted a grievous wound on the Soviet forces in southern Russia, it had come at a price. The seemingly endless steppe, sandy roads, and dust-filled air had taken their toll on men and machines. Engines were worn out, supply lines were long, and casualties had cut the strength of divisions. Replacements of both men and machines were slow in coming, and most of von Rundstedt’s panzer and motorized divisions could only field a half or less of their combat vehicles at a time. Nevertheless, Hitler insisted that his new priorities be met.

Breaking Through the Soviet’s Defenses

The main part of Army Group South began its redeployment in late September. Taking the Crimea would be the task of the 11th Army, while the 6th Army would advance toward Kharkov. The task of taking the Don Basin fell to the 17th Army, and the 1st Panzer Group would strike out toward the Sea of Azov with its eventual objective being Rostov.

General Ewald von Kleist’s 1st Panzer Group had two motorized corps (III and XIV) to use as his main attacking force. During the last week of September, German units moved into bridgeheads at Zaporozhe and Dnepropetrovsk in preparation for the forthcoming assault. Mechanics worked furiously trying to fix broken-down vehicles. The trickle of replacements coming from the West were assimilated into units as best they could, but the divisions going into battle would still be short of men and machines as the assault began.

General of Infantry Gustav von Wiethersheim’s XIV Army Corps (mot.) was deployed in the Dnepropetrovsk area facing the Soviet South Front’s 12th Army. To his north, General of Cavalry Eberhard von Mackensen’s III Army Corps (mot.) was facing the Southwest Front’s 6th Army. The first part of the operation would involve breaking the Russian line and then heading southeast, making an end run behind the South Front’s 12th, 18th, and 9th Armies. With those armies cut off, the German 17th Army under General of Infantry Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel and elements of General of Infantry Erich von Manstein’s command (mainly the XXX Army Corps under General of Infantry Hans von Salmuth) could push up the shore of the Sea of Azov. Von Kleist’s armor would be the anvil, while the 17th Army would be the hammer that would open up the rich Don basin to German forces. With that accomplished, the 1st Panzer Group would set its sights on Rostov.

On October 1, von Kleist’s units erupted from their bridgeheads. Just three days before, Timoshenko and Riabyshev had received orders to hold their positions directly from the Soviet High Command in Moscow (Stavka). It was a forlorn hope, especially with the heavy casualties already incurred in the previous months.

The Soviet forward defenses were woefully inadequate, and von Wietersheim’s panzers were able to crack them open with comparative ease. While German forces swept east, the Italian Mobile Group attached to the panzer group engaged in mopping-up operations behind the main line. In the south, von Salmuth’s XXX Corps began its drive along the Sea of Azov while elements of the 17th Army kept pressure on the western defenses of the 8th and 18th Armies.

Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler

Among the units in the XXX Corps was Lt. Gen. Sepp Dietrich’s SS Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler (LAH). Its strength was that of a reinforced brigade. During the first week of October, the LAH, along with other elements of the XXX Army Corps and the 3rd Romanian Army, battered the South Front while von Kleist’s panzers raised havoc in the front’s rear area.

On October 4, Dietrich’s men came up against concentrated antitank positions, which they immediately attacked. While the fighting was still going on, Dietrich appeared and began issuing orders to set up a temporary defensive line about 11,000 meters to the east after the positions had been captured. The move was necessary because the LAH had outpaced its neighbors on the left and right (the 8th Romanian Mountain Division and the 72nd Infantry Division) and had to wait for them to catch up to protect its flanks.

The next day the LAH’s reinforced reconnaissance battalion under SS Major Kurt Meyer headed toward the Molochana River, with other elements of the LAH following. Its 1st Company, commanded by SS 1st Lt. Gerd Bremer, took the village of Federico, about 12 kilometers from the town of Terpinnya, at 12:30 pm and pursued the retreating Soviet forces toward the town, which held a bridge that would ease the crossing of the river.

By 2 pm, leading elements of Bremer’s company were in Terpinnya itself. Fighting their way through the retreating Russians, the SS troops reached the bridge just as Red Army engineers blew it up, killing several of their own troops that were still on the structure.

Bremer was reinforced by SS Major Fritz Witt’s I/LAH and SS Major Teddi Wisch’s II/LAH, which took over the fight for the town. Meanwhile, Bremer moved his company out of Terpinnya, found a ford in the Molochana, and crossed. About three kilometers east of the crossing his men came under heavy mortar and artillery fire and direct fire from antitank positions. Leaving Wisch to clear Terpinnya, Witt pushed his battalion across the river at Bremer’s ford and established a strong bridgehead late in the afternoon.

“Ride on by!”

The South Front was now in total disarray, and Riabyshev seemed to be incapable of doing anything to rectify the situation. The same day Bremer was crossing the Molochana, Col. Gen. Iakov Timofeevich Cherevichenko arrived at the South Front headquarters. He informed Riabyshev that he was there to take command of the front immediately. The change of command would bring results in the future, but the current crisis could not be easily resolved.

During the evening, SS engineers were able to build a bridge across the Molochana after Terpinnya had been cleared of enemy troops. On October 6, the LAH was on the move again. The day’s objective was the town of Novospas’ke, about 45 kilometers to the east. With Meyer’s reconnaissance battalion in the lead, the units moved forward. Near the village of Romanovko the Germans ran into antitank fire. Soviet tanks also appeared, causing some casualties to Meyer’s antitank detachment. The arrival of the battalion’s 88mm guns soon drove the Soviets off, and the village was taken. Among the Soviet prisoners taken were several members of the 9th Army’s staff. With the capture of the village, the way to Novospas’ke was open. Later that evening Dietrich was notified that the LAH was now subordinated to von Wiethersheim’s corps. A day later it came under the command of von Mackensen’s III Corps.

On October 7, the LAH was ordered to pursue the Russians in the direction of Berdans’k and Mariupol. At the same time, a battalion of Brig. Gen. Friedrich Kühn’s 14th Panzer Division moved south to link up with the division. Berdans’k was captured by midday, and Dietrich’s men continued moving toward Mariupol.

After a few hours rest, Meyer held a commander’s conference in the early hours of the 8th. He had received a report stating that there were only weak enemy forces inside the city. Logically, Meyer should have waited for other elements of the LAH to catch up to his battalion for a concentrated assault on Mariupol. His men were exhausted after days of continuous combat, but Meyer had faith in them. He ordered his company commanders to form up and head for Mariupol at top speed.

SS Corporal Wontorra recounted his experiences in the LAH divisional history. “My orders were simply to push on past the Russians,” he said. Eventually the motorcyclists ran into a group of around 30 Russians marching toward the city. “I remembered Meyer’s words ‘Ride on by!’” he continued. “By now my driver was asking me what he should do. ‘Give her gas and drive on by’ was my answer. When we caught up with the Russians they looked at us in disbelief and had no time to grab their rifles. We rode on past. It had worked beautifully.… We passed one column after another. We often passed artillery being pulled by tractors.”

Before long, Wontorra’s motorcyclists were in the city itself. Behind him came the rest of the battalion, followed by Wisch’s II/LAH. By noon the city of approximately 250,000 people was firmly in German hands, and a bridgehead had been established on the eastern bank of the Kalmius River.

The Death of Andrei Smirnov

The bulk of the 18th and 9th Armies was now effectively isolated, with von Kleist’s forces in their rear and XXX Corps at their front. Soviet units were suffering horrendous casualties, and general officers were not immune from the carnage. The commander of the 18th Army, Lt. Gen. Andrei Kirillovich Smirnov, was at his command post near the village of Popovka when German artillery killed him. He was later buried by German troops, who placed a marker on his grave that asked their soldiers to fight as bravely as this Soviet soldier. The inscription was in German, Romanian, and Russian.

Smirnov’s artillery commander, Maj. Gen. Aleksei Semenovich Titov, died the same day when he was hit by artillery fire as he was overseeing the withdrawal of his forces. As German infantry advanced, he joined his gun crews in an effort to drive them off. He was killed by a direct hit on the gun he was manning.

The following day, Chief of Staff of the Army General Franz Halder wrote in his diary, “We must exploit the unexpectedly swift capture of Mariupol by the SS Adolf Hitler by pushing through as quickly as possible to Rostov, and perhaps even crossing the Sea of Azov. The Italian divisions unfortunately are so ineffectual that they can be employed for nothing more than passive flank cover behind rivers, but not for broadening the attacking front of the [1st] Panzer Army [Panzer Group 1 was not officially renamed 1st Panzer Army until the last week of October].”

“The Battle at the Sea of Azov is Over”

It did not take Berlin long to announce another great German victory to the world. An October 11 communiqué from the Wehrmacht High Command began with “the battle at the Sea of Azov is over.” It went on to state that the losses to the 9th and 18th Armies included 64,325 prisoners, 126 tanks, and 519 guns. It also mentioned that Army Group South had captured 106,365 prisoners and destroyed or captured 212 tanks and 672 guns since September 26.

The 13th Panzer Division under Brig. Gen. Walter Düvert had now moved up to Mariupol and had established contact with the LAH. With the rest of the division moving into the city, Dietrich’s men were ordered to advance to the next objective—the city of Taganrog, which was a little more than 100 kilometers away. Meyer’s reconnaissance battalion met no opposition as it sped eastward, and it reached the town of Nossavo, about 11 kilometers northwest of Taganrog, by 3:30 pm. A platoon was then sent to reconnoiter the nearby town of Nikolaevka. It reported that the western edge of the town was heavily fortified and that any attack route would be clearly visible to enemy positions on the east bank of the Mius River. There would not be another Mariupol-like coup this time.

The bridges at Nikolaevka were of critical importance if the advance to Taganrog was to continue. On October 12, orders were given for the LAH to establish a bridgehead across the river, while the 13th and 14th Panzer Divisions moved up to protect its flanks. Meyer’s reinforced battalion attacked the Soviet forces on the west bank of the river supported by Witt’s I/LAH.

Successful penetrations were made, but the SS were soon met with a hail of fire from the eastern bank that stopped the assault in its tracks. It soon became evident that the attack would not succeed, and after a few hours of fighting Meyer and Witt were ordered to withdraw.

Crossing the Mius

Meanwhile, Dietrich had received reports that the Soviets had constructed an emergency bridge across the Mius at Prokovskoya, about 18 kilometers to the north. He immediately sent Wisch’s II/LAH to check on the report, which turned out to be correct. Once again, however, Soviet defensive fire made it impossible to take the bridge by storm. Despite the day’s setbacks, Dietrich was still determined to get across the river.

Waiting until darkness fell, SS 1st Lt. Heinrich Springer took his 3rd Company along the bank of the Mius north of Nikolaevka. Sending a platoon across by raft, Springer was able to establish a bridgehead on the eastern bank. By 9 pm, his entire company had crossed the river and had taken a commanding position overlooking the town. Witt immediately sent the other companies of his 1st Battalion across to reinforce Springer. The III/LAH, under SS Captain Albert Frey, soon followed.

The following day, Wisch used his battalion to make another effort to capture the bridge at Prokhovskoya. With the help of assault guns the battalion was able to close on the bridge, but intense enemy fire once again prevented its capture. Wisch suspended the attack after suffering heavy casualties, and late in the day he turned the sector over to Düvert’s 13th Panzer.

Realizing a bridgehead north of Nikolaevka had been established, the Soviets attacked Witt and Wisch—first in company strength and then in battalion strength. The attacks were supported by Red Air Force bombers, artillery, and an armored train, but were repulsed with bloody losses.

Düvert turned his engineers loose later in the day, and by midnight an eight-ton bridge had been built over the Mius, allowing more German infantry to occupy the eastern bank. With the added strength protecting its flank, it was time for the LAH to move on Nikolaevka.

During the 14th, Witt’s men fought their way into the center of the town, meeting heavy resistance along the way. The Soviets fought for every house, stubbornly refusing to give way until the last man was either killed or wounded. The Red Air Force also appeared time and again, bombing friend and foe alike. Fighting raged throughout the night, giving the men on either side no time for rest.

Armor was now becoming available to the German forces on the east bank. Düvert’s engineers had constructed a heavier bridge, capable of supporting his panzers, which were now crossing the river, albeit under Soviet artillery fire. This reinforcement kept the Russians from reinforcing Nikolaevka from the north and east, allowing Witt’s battalion to take the town by midafternoon on the 15th.

The Soviet troops trying to stem the advance of Panzer Group 1 had suffered greatly, but the remarkable resilience of the Red Army was beginning to make itself known. During the third week of October a new army, the 56th, was formed under the command of Lt. Gen. Fedor Nikitovich Remezov. The 56th, consisting of six rifle and six cavalry divisions, was given the task of defending the approaches to Rostov.

Assault on Taganrog

With Nikolaevka taken and more German units flowing across the Mius, the advance on Taganrog could now continue. The LAH still had the mission of capturing the city, and at 5:30 am on October 17, Witt’s reinforced I/LAH moved out with the southern section of the city as its objective. SS Major Günther Anhalt’s IV/LAH was ordered to take the southwestern shore along the Gulf of Taganrog, while Wisch and Frey would hit the city from the east.

The attack went according to plan, with units of all four battalions fighting in the city itself by midmorning. By 3 pm, the Soviets had been pushed into the southeastern part of Taganrog, and Witt’s battalion had occupied the city’s harbor installations. A member of the LAH wrote: “As we approached the city, the roar of explosions announced the Russians’ intent to abandon it. The clouds of smoke from burning fuel and ammunition stores stood like giant mushrooms above the city and darkened the azure sky.”

With most of Taganrog in German hands, new orders came down from corps command. The 13th Panzer Division was to expand the bridgehead at Sambek, about 15 kilometers northeast of the city, with the 14th Panzer guarding the corps’ northern flank. Meanwhile, the LAH was to continue to mop up any nests of Soviet resistance remaining in Taganrog.

Those units, along with the rest of von Kleist’s panzer group, needed both rest and supplies. Fuel was at a premium for most of the divisions in the command, and the supply route stretched hundreds of kilometers to the west. Weather was another issue. German units farther north had already experienced the mud of the Rasputitsa, and in the central and northern regions of the Eastern Front snow had already fallen in some areas. Vehicles, especially wheeled vehicles, became mired in the mud that was once a sandy road, and the long supply lines made getting the necessary fuel, ordnance, and other materials to continue the advance an arduous trip.

Supply Lines Stretched

On October 19, von Mackensen issued the following order for the capture of Rostov. “The 13th Panzer Division and the LAH are to attack at 0530 hours on 20.10 by moving the bulk of their forces across the line reached today. The LAH is to halt its progress when it is level with the 13th Panzer Division.” Once again, the 14th Panzer would provide cover for the corps’ northern flank.